Move over Michael Keaton and Jeff Goldblum: Pittsburgh has a new film star. Just don't expect to see him on the cover of People any time soon. Because not only is Dan Kovalik, a local labor attorney, an unlikely celebrity ... he is also legally prohibited from talking about the movie that has put him before an international audience.

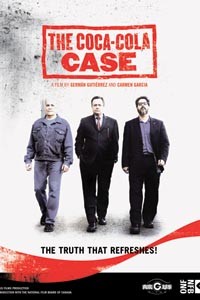

Kovalik has a starring role in a recent documentary, The Coca-Cola Case. Made by Canada-based filmmakers Carmen Garcia and German Gutierrez, the film documents a years-long legal battle over the company's operations in Colombia.

As an attorney for the plaintiffs, Kovalik is one of the key players. The film opens with Kovalik speaking at a press conference in Bogota, where he decries the high murder rate among labor activists in the country.

From there, the film outlines the allegations against Coca-Cola: that its Colombian bottlers were complicit with the kidnapping, beating and murder of union leaders by Colombian paramilitaries -- and that the soft-drink giant could have done more to prevent the crimes.

Kovalik serves as general counsel for the United Steelworkers union, whose national headquarters are in Pittsburgh. With a penchant for speaking out on labor and social-justice issues in Latin America, he's no stranger to media attention. Well before the film was released, his battle with Coca-Cola generated headlines, as did a similar lawsuit against a coal company.

But he is uncharacteristically quiet these days: When contacted by City Paper about the movie, Kovalik said he is legally prohibited from commenting.

Colombia has been wracked by decades of violence stemming from a variety of factors: left-wing guerillas, right-wing paramilitaries and powerful drug cartels targeted by the U.S. government's "War on Drugs." Union organizers -- at Coca-Cola bottling plants and elsewhere -- have often found themselves the target of violence from the paramilitaries. And Coca-Cola workers said they'd been arrested under false pretenses, beaten up, and even been kidnapped by paramilitaries working in conjunction with local plant managers.

The question at the heart of the documentary is presented by Terry Collingsworth, the executive director of Washington, D.C.-based International Rights Advocates. "How legally accountable is a major corporate brand like Coca-Cola for the activities in its far-flung plants in places like Colombia?" Collingsworth asks.

The Colombian union Sinaltrainal decided to find out by filing a half-billion dollar lawsuit. The action was filed in 2001 in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida, using the centuries-old Alien Tort Claims Act. That law allows foreigners to sue in American courts for violations of "the law of nations or a treaty of the United States."

Filmmaker Gutierrez says he learned about the lawsuit from Kovalik himself. Gutierrez met the Pittsburgh attorney while making another film about Colombia's political violence. This film, Gutierrez says, is intended "to show the solidarity of some American people with the unions in Latin America." Kovalik and Collingsworth, he says, "are against injustice all over the planet."

Not surprisingly, then, Gutierrez features Kovalik prominently. Viewers see him walking in Downtown Pittsburgh, and working amid mountains of paper and a poster of revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara. And they hear him observe that Coca-Cola is vulnerable to the bad publicity the lawsuit brings.

"Its goodwill is critical to its ability to sell products, because all it sells is sugar water," Kovalik says on camera. "Its marketing and good name is really all it has."

Atlanta-based Coca-Cola says the lawsuit's allegations are nonsense. Nearly one-third of workers at its Colombian bottling plants are unionized, the company says, as compared to just 4 percent of the rest of the country's workforce. They are also better paid, the company contends.

"The allegations made in the film have been reviewed multiple times" by U.S. and Colombian officials, says company spokesperson Kerry Kerr.

Indeed, the Sinaltrainal suit was tossed out in 2006. U.S. District Court Judge Jose Martinez said he didn't have jurisdiction over bottling plants outside U.S. borders.

"Demonstrating indirect liability for human rights abuses on the part of corporate entities is an inherently difficult task," the ruling added.

In a statement at the time, the company asserted that "the claims in the suit ... are inaccurate and based on distorted versions of events."

But the plaintiffs have never truly had their day in court, says Ray Rogers, an activist with the "Campaign to Stop Killer Coke." Because Martinez dismissed the case on jurisdictional issues, he says, there was never any trial or legal discovery process -- so the allegations have not been thoroughly reviewed.

It doesn't seem likely that will change. A federal appeals court upheld Martinez's ruling last year. And Kovalik himself can't comment on the movie because of a scene in which Kovalik, Collingsworth and the plaintiffs discuss details of out-of-court negotiations with Coca-Cola. Up for discussion: a proposal in which Coca-Cola would denounce anti-union violence and pay into a fund to compensate its victims.

The two sides never reached an agreement. But the film revealed negotiations that were supposed to be confidential, says Coca-Cola spokesman Kerr, and the courts have agreed that those confidentiality agreements should be binding. Kovalik's silence indicates that on this much, at least, he and the company agree.

The company also sent a letter to the filmmakers notifying them of the requirements. But Kerr says Coca-Cola has decided not to pursue further legal action stemming from the film, which has been widely screened in Canada.

Neither Gutierrez nor Rogers were ever legally required to keep quiet -- which is why they were able to talk to CP. Gutierrez also makes no apologies for documenting closed-door discussions.

"We are filmmakers," says Gutierrez. "We are journalists. ... The public should know about that negotiation." He says the movie has been vetted by their attorneys and believes it is on firm legal ground. Even so, getting the company's letter was "very scary," he says. "It's Coca-Cola."

Such legal skirmishing isn't unprecedented, says Charlie Cray, director of the Center for Corporate Policy, a watchdog group for corporate accountability. But Cray says it's tough to generalize about how common it is for companies to take on activists. "I think it depends on the nature of the company, the culture the executives have and the legal advice they're getting," he says.

In any case, Coca-Cola may not have heard the last of Kovalik. Ray Rogers, whose campaign has led to the soft drink's removal from some college campuses, says a new lawsuit is in the offing. This suit, Rogers says, will concern violence directed at labor organizers in Guatemala.

"The film," he adds, "has raised the campaign to another level."