One thing about political cartoonists: You never need to ask them, "But no, what do you really think?" Forsaking the measured tones of their editorial-page brethren, they offer the sort of commentary best expressed through pure mockery (if not vitriol).

Among the nation's top editorial cartoonists is Rob Rogers, of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, who marks 25 years of cartooning with the new 368-page retrospective No Cartoon Left Behind! (Carnegie Mellon University Press).

Rogers, whose politics have remained proudly liberal through five presidents, inks several weekly panels for the P-G (including his Pittsburgh-themed "Brewed on Grant"). His work is distributed by United Features Syndicate, and regularly reprinted by the likes of The New York Times and Newsweek.

Rogers, 50, grew up in Philadelphia and Oklahoma; he was hired by the old Pittsburgh Press straight out of Carnegie Mellon University's graduate art program. He joined the P-G in 1993, after the Press folded. At a favorite hangout -- Butler Street's Dozen Cupcakes -- the Lawrenceville resident spoke with CP about his craft and the state of cartooning.

Let's talk cartoons. Here's one from last year's presidential campaign. How did the idea form?

There had been a lot of stories about Obama being criticized for not wearing a flag pin. Of course, I thought that was the most ridiculous thing in the world, because wearing a flag pin doesn't make you any more patriotic than starting a war in Iraq does. I wanted to show that even if he did wear the flag pin, people would still criticize him.

At first I didn't think of it as a burka. Sometimes that's what happens with ideas. You're drawing it out and then the visual comes.

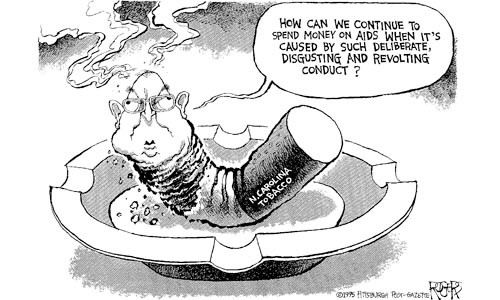

How about this one, from 1995?

Jesse Helms was part of the right-wing family-values moralist [Congressional contingent]. And so he was always ranting about gay rights and how immoral it was. I'm always trying to find ways to look at these people and say, "Well, where's the hyprocrisy?" And it's usually pretty blatant.

It wasn't until I started really working out the sketch that I thought, well, I could sort of make him ... a butt.

He's half crushed-out.

But he's still smoldering. His influence wasn't totally snuffed out yet.

This Hiroshima one, from 2005, was controversial.

This one still gets a gasp when I show it in my slide shows from time to time. I'm referring back to World War II, where people thought ... "[T]hat was a different time, we could do no wrong."

The little kid, the only thing he would remember was 9/11. He just knows that they're showing this explosion. So a lot of veterans felt that I was calling them terrorists.

This September 2001 cartoon was actually killed.

This one I did after 9/11 because there were a lot of people who couldn't understand why people would hate America. I thought, "I can think of some reasons why people would hate America."

And my editors looked at it and said, "Everyone here hates it." This was [two weeks] later. Nobody wanted to criticize the president. All the comedians were off the air. And it just infuriated everybody on the editorial staff, because they were still standing in the wreckage, emotionally.

Later, when they were including this in a book of killed cartoons, the editor was like, "I killed that?"

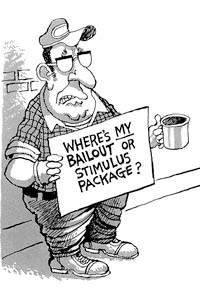

Here's your Everyman. Is there a model for him?

It's all based on versions of my dad. And then I would just occasionally make him bald. At first he wasn't that happy about it. And then people at work would say, "Hey, I saw you in the cartoon again today. You were a plumber."

He passed away last year. But he got a kick out of it, after getting over the fact that I was drawing him in a not-so-flattering way.

With the fragmenting of popular culture, is it harder now to find references most people will get?

Yes. Because you no longer have three major TV stations that run the shows, and everybody knows what the shows are. You may be referencing a television show that's on one of the lesser-known cable channels, and you may watch it every week, but your editor doesn't, and maybe half the readers don't. You have to wait till it gets really saturated: If we're doing stories on it, in our paper, or I've seen them on the cover of USA Today, then it's probably safe to do a cartoon about it.

What's changed in editorial cartooning?

What's happened with all journalists now, they're multi-tasking. Now I'm doing a blog. I occasionally Twitter, I have Facebook. Now we're doing this extra [online] thing called PG+. So there's all these ways we're being asked to do extra work, but for the same amount of money -- and in some cases, less money.

I was sort of the last wave of the '80s where they were actually hiring cartoonists at most newspapers. If someone left they would rehire. Now of course all the newspapers are folding, and merging.

Now ... even cartoonists who have lost their jobs are still doing stuff on the Internet, are still syndicated, which means that their stuff is going out electronically. But the pay is not the same.

How many political cartoonists remain?

When I started there were around 200 full-time full staff positions. I think that's been halved. It's probably around 80 people like me, who actually do it for a living. The fact that there are any of us is remarkable.