When Manomano Mukungurutse lectures, he dances.

Standing at the front of the classroom, his arms flail and his thoughts wander. Like a tennis player preparing to return a serve, Mano bounces on the balls of his feet, anticipating the next question he'll pounce upon. Then, smack! His hand slaps his forehead -- an idea rattles loose.

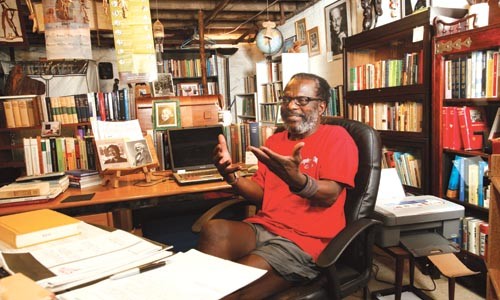

Mano's appearance is a study in contrast. He's got the professorial glasses and the pensive, squinting eyes to match. But his T-shirt -- which proudly declares: "Normal people scare me" -- is stretched and his matted, graying black hair is unkempt. His deep, resonant voice issues from a 5-foot-6, 125-pound frame

Mano has taught everything from philosophy to geometry, criminology to anthropology. For his students, who populate numerous local campuses, the experience can be enlightening or confusing. In one breath, he quotes Albert Einstein, the next, Frederick Douglass. Even the ends of his sentences seem open-ended: Mano typically rounds off his thoughts by observing, "That's the idea, very much" or "And so on and so forth."

"I've always had this native intuition that everything is connected to everything else," says Mano. "Not many people think in the crazy way that I do."

In an age when knowledge is becoming increasingly specialized, Mano is a jack-of-all-trades, trying to master them all. To friends and colleagues, the Zimbabwean professor represents one of the few true, free-thinking intellectuals, a man whose thinking knows no bounds.

"This guy is so tiny, yet his tininess mocks the grandness of his ideas," says Dr. George Yancy, Mano's colleague at Duquesne University. "He's kind of like a magician -- what you see is not what you get."

That's the idea, very much.

His Eyes Were Open

Mano was born in the small village of Marume, in southern Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia). But he doesn't know his birthday, or even the year. Mano was not born in a hospital, so he can only offer an approximate birth date: Often-stamped travel records list it as Nov. 17, 1942.

Born prematurely into a peasant family along with three older siblings, Mano wasn't expected to survive infancy. He spent nearly the first year of his life without being named.

"In my particular ethnic group, you don't waste a name," says Mano, who was part of the Mashona tribe. "People were not sure how long I was going to survive."

Eventually, Mano says, his stubborn aunt rebelled. Near the time of his first birthday, she named him Manomano, meaning "the unexpected, pleasant surprise."

Surviving was the next surprise, and Mano would go on confounding expectations for the rest of his life.

As a young child, Mano remembers discovering geometry on his own. In the village, he says, two rows of houses ran parallel to one another between two creeks. Standing at one creek, he recalls looking down the rows of houses and being confused by what he saw. "[The houses] seemed to be converging," he says. "So I would run that way and see, no, they were still open.

"It was just fascinating to me," Mano continues. "My sense and interest in geometry were very much formed then."

But numbers posed a serious dilemma for the young boy. "When I learned to write numbers, I started having a problem with odd numbers," he says. "I didn't like them.

"I fell in love with even numbers," Mano explains. "Two, four, so comfy! Seven, eh! Five, forget it! Three, ooh!"

In school, Mano remembers his teacher asking him why he preferred even numbers. "I said to her, 'I see a sense of equality and fairness,'" he recalls.

From early on, he says, Mano had a "native intuition" concerning issues of religion, politics and gender equality. It began innocently enough. As a young child, Mano says he herded cattle, worked the fields and attended school, just like all the other children. But unlike most others, he rebelled against his village's cultural and religious traditions. He disliked, for example, the notion that fetching water was considered a job for women only. So, to the confusion of the villagers, Mano says he hoisted a bucket atop his head and joined the girls.

Such behavior -- and Mano's stubborn, rambunctious personality -- earned him a nickname when he was only about 7 years old: Chimusoro, "The Incorrigible One."

Mano says he loved religion. He just didn't believe in God. "I was misunderstood," says Mano, noting that most villagers were Christian, while others practiced various indigenous religions. He enjoyed the Bible's stories as wonderful literature, not the word of God. "They took it as just anti-religion."

In elementary school, Mano recalls, he gave up for Lent a vegetable that wasn't even in season. "The school was not very happy about that one," he says.

In sixth grade, his cousin reported him to school officials for praying with his eyes open. "One of the teachers said, 'Chimusoro, Thomas said your eyes were not closed in assembly prayer,'" he remembers. "I said to him, 'Well, if my cousin's eyes were closed, how could he see that mine were open?'"

The superintendent was unimpressed by Mano's logic, and Mano was soon expelled from the school. All told, Mano says he was expelled from kindergarten, third grade, sixth grade, junior high school and high school.

"Most of the schools kept making mistakes," he jokes. "They would admit me and wonder why I was expelled [before]. But then the politics, religion, my questions would come up, and then I would be expelled again."

But Chimusoro wasn't going to change, and his parents didn't want him to -- even though they were the ones being blamed for his rebelliousness.

"My parents were angels," Mano says. After being kicked out of a school, "My father would say, 'We'll have to find you someplace else.'"

As a teen-ager, Mano says he grew interested in politics, and by age 13, he became involved in the country's labor movement. But he says his work organizing strikes and demonstrations earned him two arrests in the span of roughly three years. And for school officials, Mano's second arrest was the last straw.

"I was expelled for good," he says, adding that he finished high school through correspondence courses from home. "I couldn't go to high school in the country."

In defense of Mano's final expulsion, in fact, one teacher wrote a letter describing what he considered Mano's "unteachable" nature. In it, the teacher said "I was just a useless, nutty, delinquent kid," Mano recalls. "'Chimusoro will always be Chimusoro.'"

The 'adopted son' of Pittsburgh

Chilly, insular Pittsburgh might seem an unusual place for a free-thinking Zimbabwean to end up. But it may be the perfect place for an unsettled mind like his to settle.

Mano calls himself the "adopted son" of Pittsburgh, and he's lived here for 15 years -- the past 10 of which he's spent in Squirrel Hill, with his wife, Martha Mantilla.

"Sooner or later, you're bound to bump into him," says Janice Cavrak, Mano's bartender at The Squirrel Hill Café (a.k.a. The Cage) for the past 10 years. And sometimes you're likely to bump heads with him as well.

"You know the old saying, 'You don't discuss religion, sex and politics in here'?" Cavrak says. "Well, he has gotten into some serious arguments here."

Still, she says, "You can't help but love the guy."

"He is widely known in this neighborhood," adds Stephen Sefcik, a bar regular who's known Mano for almost as long as the Zimbabwean's been in Pittsburgh. "Mano's always an enjoyable fella. I've never seen him in a bad mood."

Mano's journey to Pittsburgh was a long and winding one. Worried that his youthful antics would catch up with him at the University of Zimbabwe, he chose the University of Dar es salaam, in Tanzania. But the school was too conservative for him. After a year, he transferred to Kenya's University of Nairobi -- and again stayed for only a year.

"I am what you call a transfer freak," says Mano.

Throughout much of the 1970s, in fact, transferring schools became part of Mano's routine. All in all, he attended seven universities around the world. Among them were Moscow State University, in the Soviet Union; Cornell University, in the U.S.; and the University of Cambridge, in England.

"I might have been running away from boredom. I don't want to be bored," he says. "These different experiences were an integral part of my formative years, in part because of fear of being narrow-minded."

Not surprisingly, then, Mano changed academic disciplines about as often as he changed schools.

"I would just pick something and study," he recalls. "Some of my advisers in all of those colleges were upset with me. They wanted me to declare a major."

Mano started off studying philosophy and criminology. Then anthropology and economics. Eventually, at Cambridge, he says a Chinese physicist got him interested in physics and mathematics.

"I was a mess," says Mano, who also picked up more than a half-dozen languages during his travels. "All these years, I was just studying whatever I wanted."

Altogether, Mano says he has three undergraduate degrees from his studies in the U.S. and a few more from universities outside the country. He also has a master's degree from the University of Pittsburgh.

But "Degrees were never important," says Mano, who later continued his studies at schools like Duquesne, where he studied philosophy for a year, and Carnegie Mellon, where he studied cybernetics and public policy. "I just wanted to learn."

"I respect people with Ph.D.s," he adds. "But I'm not jealous of them."

"I think that Mano privileges thought over academic certification," explains George Yancy, a philosophy professor at Duquesne. "The degree doesn't quite guarantee thinking. It certainly doesn't guarantee creativity of thought, intricacy of thought and depth of thought. And that's what he's got."

"His teaching has no bounds," adds Joe DeBlassio, chair of Community College of Allegheny County's math department. "He has an act of relating philosophy to everything. ... He works very hard to try and have the students become very in-depth thinkers."

He also works hard to defy what Yancy describes as the "banking system" of education. "There is the belief that the teacher teaches and the student listens," he says, "that the students are empty vessels and you take your knowledge and deposit it into their heads. Instead, Mano sees students as co-workers. He creates a fascinating space of equality."

Without a doctoral degree in any discipline, Mano isn't exactly on the tenure track. But thanks to Pittsburgh's high concentration of colleges and universities, Mano doesn't need a guaranteed teaching post to get by. In his teaching career, he has worked as an adjunct professor at numerous local universities: CCAC, Duquesne, Carnegie Mellon and Chatham University. And at each one, he's taught various subjects, everything from sociology to geometry.

"I think my teaching style is a perfect match for the intellectual, social and cultural diversity that Pittsburgh provides," says Mano. The schools "furnish the relentlessly unsettled mind."

"For my research and the things I want to do, I have resources here," he adds. "All these universities and colleges are very familiar, and I've been treated very well."

And on each of those campuses, he's met with a wide array of responses from students. "There are those who understand my madness, there are those who don't quite understand, and there are those in the middle," says Mano. He adds that he tries to limit the stress on his students by assigning them take-home papers rather than in-class exams.

It doesn't always help.

"I learned nothing in his class," reads a Duquesne student's post about Mano on ratemyprofessor.com, a popular college Web site. "He rambles on about things that don't even pertain to sociology."

Another post from a CCAC student simply reads: "ahhhh!"

Still, other students find Mano's teaching style enlightening. "Great teacher," one CCAC student writes. "He will really open your mind!"

"This man is a nut, but I learned a lot," writes a Duquesne student. "[T]ake his class."

"My teaching method is in some sense eclectic," acknowledges Mano. The blackboard alone can give Type-A students fits: Mano's strokes are hectic, the ideas displayed as frantically as you imagine them inside his head.

While teaching a summer adult course at Westminster College one semester, Mano remembers a student praising his teaching style after he finished a lecture. Another student, however, "just said, 'Yeah, you are a wonderful teacher, but sometimes you have a tendency to lose some of us,'" Mano recalls with a hearty laugh. "After that we went drinking."

'The Cave'

But the conversations that matter most to Mano are those that take place with his books.

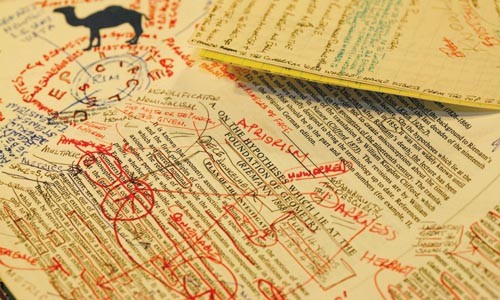

"I talk to them," he says, opening a text with page margins completely littered with notes, underlines and circles. "I say, 'Damn! How could you think this way?' Marx says books are friends. I love to talk to my friends."

He does so in the basement of his Squirrel Hill home -- or, as Mano calls it, "The Cave."

Descending the narrow staircase that leads from his kitchen is like walking into an underground bunker of knowledge.

"Welcome to the People's Cave of the Millennium," he says at the bottom of the stairs.

It's easy to mistake Mano's basement for a forgotten branch of the Carnegie Library. There are books to your left, books to your right -- more than 2,000 in all, he estimates. They line the walls, they sit on tables and they lie scattered on the floor.

"When people make babies," Mano says, "I read books."

Navigating the Cave is dangerous. First there are the tables and shelves of books you must wend your way through, then there's the artifacts dangling from the ceiling. (Mano and his wife, who is from Colombia, collect artwork from Africa and South America. Many artworks hang from strings in the Cave.) With his small stature, Mano doesn't have much trouble with the obstructions above, but taller guests are obliged to duck.

Taped to the side of a bookshelf reads the Cave's motto: "Relentlessly striving to cultivate intimate friendship with wisdom."

While some bookshelves are devoted to single subjects, like philosophy or law, others are a mix of various disciplines. Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times sits just one shelf above Africa's Search for Identity. Three volumes of Russian philosophy rest just inches from a calculus text and a physics book.

"Each discipline is a key to unlock the mystery of the universe," Mano says, sipping a Heineken in the dimly lit chamber. "I've always thought about the interconnectedness of ideas. I have not been able to divorce [them]."

Lately, Mano has been spending much of his time in the Cave. He's currently on a year-long break from teaching in order to focus on studies of his own. For the first time, he says, "I'm putting my madness into writing."

So now, of course, his home is scattered with traces of his writing -- on napkins, paper scraps and books. And his wife has only herself to blame.

"One day, she said, 'Honey, if you do not write, how do some of us know what you know?'" he recalls. "She is the one who has single-handedly persuaded me to write."

Mano's restless mind both defines and confines him, and it also frustrates his wife. While Mantilla has convinced him to write, she has yet to get him to focus. As he's always done, the professor is studying multiple disciplines. In fact, his current research and writing is focused on not one, but seven different themes. These include everything from the unity of science and social movements to social and political philosophy and studies comparing the political styles of Barack Obama, Frederick Douglass and Nelson Mandela.

"Sometimes my wife says, 'Why don't you stick with one and finish it?'" says Mano. "She gets mad at me sometimes."

In his studies on the unity of science, for example, Mano is trying to argue that the natural and social sciences must be married in order to solve many of the world's issues. "When we try to solve some social problems, like AIDS, we ought to teach our students that it's not just biology that we need," he explains. "It's not just chemistry. We need psychology, we need anthropology."

His work on social and political philosophy, on the other hand, takes the professor back to Africa. His overriding argument is that, socially and politically, the continent should be studied as a whole, rather than regionally. "Most of the problems [Africa] has are common problems to all [African countries]," says Mano, citing famine and AIDS. "We need this Pan-African awareness to recognize that when one country suffers, the rest of the countries are affected."

But of all Mano's research themes, one concept in particular ties them together: inversion. And it's the subject of the book he's currently writing.

Inversion, says Mano, means the reversal of order, sequence or relations. In politics, for instance, inversion takes place when a government is overthrown and replaced by a new regime. And in law, he says, it takes place whenever a Supreme Court ruling results in overturned verdicts.

Mano's working thesis: "At the center of human thought, inversion is everywhere, and it helps us understand the change, development and growth of knowledge," he says. "Inversion is central to the development of human knowledge."

You could also argue that it's central to who Mano is. All his life, the Zimbabwean has turned education on its head, collecting and disseminating knowledge even as he rebels against its basic principles and traditions.

Mano's intellectual world is not one obsessed with degrees and professional stability. It's the knowledge he's after.

And so on and so forth.