Across the country, cities and counties are freely releasing online public data that has long been locked in cabinets, hidden behind busy clerks or in ancient proprietary software. And efforts to make such data widely accessible are sparking innovation, helping to create new businesses and increasing the quality of life.

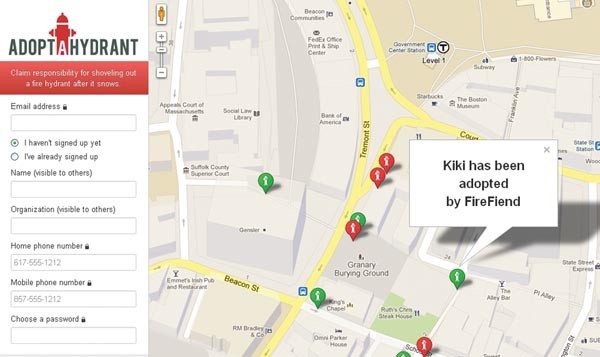

In New Orleans, for example, you can search online for the status of a blighted property, tracking its progress through the system to a final hearing before a judge. In Boston, data releases created the "Adopt-A-Hydrant" program, which lets volunteers "claim" hydrants to keep clear during winter snowstorms. There's also an application called "Where's My School Bus?" that lets parents see real-time information about when the bus will arrive at their children's stops.

Even Gov. Tom Corbett's administration has begun embracing the idea, launching www.pennwatch.pa.gov at the end of 2012. The site contains datasets related to state budgeting and spending, including state-employee salaries.

It's a movement the city of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County should join — and one Philadelphia is already taking part in. In April 2012, Mayor Michael Nutter signed an executive order pledging greater transparency through data releases. In September, he hired Mark Headd as the city's Chief Data Officer to coordinate the effort.

"There is a growing awareness of the value of the data cities have," Headd says, adding that the idea is being pushed particularly by journalists and tech-sector entrepreneurs.

As those reporters can tell you, government agencies hold countless documents that never see the light of day, even though they are considered part of the "public record." Ordinarily, dislodging such information requires filing time-consuming open-records requests, which government employees must respond to. But simply putting all public information online would be more cost-effective in the long run, says Michael Berry, vice president of the Pennsylvania Freedom of Information Coalition.

"In this day and age, it's a lot easier to put information out on a website than it is to respond to requests on paper," he says.

Headd notes that posting such data makes economic sense in other ways. In Philadelphia, the city's data has been used to build a number of mobile applications to help users navigate the city's transit system.

"The transit agency benefits because it doesn't have to spend the money to build these apps. And if we're lucky, we get a new business out of it," he says.

Philadelphia has been releasing data sets once a week or once every couple of weeks for the past few months, adding to a repository on opendataphilly.org that already contains about 200 databases. Material includes everything from a list of food vendors registered with the city to campaign-finance records, from voting data to crime information. Importantly, the data is collected in formats that make it easy to download and use.

For now, the data is free for anyone to access, including commercial developers.

"For many of the datasets, there is an argument that this data has been paid for already by tax dollars," Headd says.

In larger cities especially, employees like Headd are talking about standardizing the datasets, so data from different places can be combined and made even more powerful.

For now the effort is informal, but Headd notes that if municipalities in Western Pennsylvania went this direction, they would benefit from collaborating with Philadelphia, taking advantage of the progress that has already been made.

"I think this whole movement, it's a change in the way governments think of themselves as managers of data," he says. "It's less about owning it and more about becoming stewards" of a public asset.