A new study of life expectancy for Black populations across America found those living in Pittsburgh are likely to live about three years less than the national average.

Released last week, the Black Progress Index assessed a series of quality-of-life metrics that the authors say best predict an individual’s life expectancy. The study, co-authored by the NAACP and Brookings Metro, found that Black Pittsburgh residents live for 71.3 years on average, compared to the national mean of 74.4 years for Black Americans.

The study aggregated multiple datasets to determine what factors best predict life expectancy without necessarily identifying how they contribute to longevity. High levels of religious observance were, for example, found to correlate with lower life expectancy even though the authors note religious believers often have improved assessments of their own health.

Other factors, like household income, air pollution, and levels of gun-related deaths, have clearer implications for life expectancy.

In Pittsburgh, low homeownership rates and poor numeracy standards among public school students were noted as the biggest individual predictors of lower life expectancy for Black residents, with each subtracting six months of predicted life. The low average household income of $33,000 for Black Pittsburghers was also highlighted as a contributing factor.

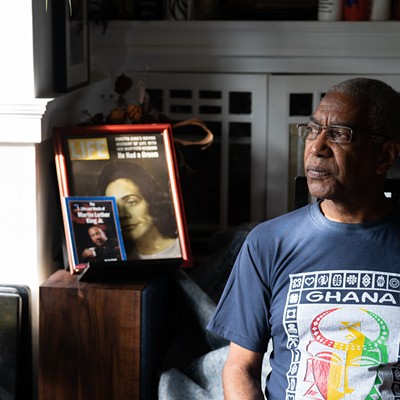

Dr. Jerome Gloster, a pediatrician who runs Homewood-based Primary Care Health Services, tells Pittsburgh City Paper that studies on the health and well-being impacts of structural racism highlight its negative effect on people's sense of control over their environment. This, Gloster says, could touch on several factors in the Black Progress Index, such as income, education, and family structure.

Gloster is an advocate through the Black Equity coalition and says his experience as a health practitioner confirms the negative consequences long-term renting can impose on some families. He expands on this, saying household issues like mold or cockroaches can exacerbate asthma and otherwise harm health, and that relying on a landlord to perform maintenance often means waiting longer for a fix — or sometimes never getting one.

“When we’re trying to work together to improve their child’s health and outcomes, we’re bumping up against this area and asking what we can do to work with these landlords,” Gloster says. “If they own their home, they have control over those things.”

The latest report follows previous studies flagging Pittsburgh’s disproportionately negative quality of living standards for Black people. Notably, a 2019 study commissioned by Pittsburgh’s Gender Equity Commission found Pittsburgh to be among the least livable U.S. cities for Black women, but also poor for Black men. A year later, 12 members of the Allegheny County Council referenced this report while citing racism as a public health crisis.

The authors of the new national index say it is intended to “empower local leaders with information to excite civic action."

“Research from the Black Progress Index will provide insights into the most impactful conditions that affect their quality of life and give communities goals and benchmarks to track their advancements,” says Andre M. Perry, senior fellow at Brookings Metro.