Don Mains has been trying to get someone to listen to his story for months. He called his local Armstrong County media, and even larger Pittsburgh-area outlets, with no success. He feels it’s imperative to tell his story about his town, Ford City, which he says has been hurt by the alleged sabotage of a major project meant to revitalize the borough. Mains believes if his version of events is exposed, Ford City’s name will be cleared and the borough can thrive again.

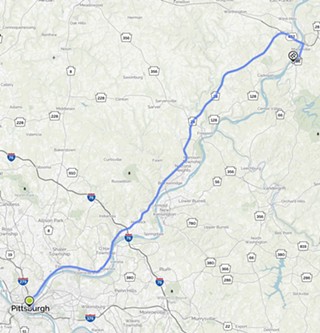

“The newspaper [used to] cover everything that we did; that was so important for community organizing,” says Mains, an outspoken advocate and longtime resident of Ford City, located about 45 minutes northeast of Pittsburgh. “If you don’t have media and you don’t have the call to action, it’s virtually impossible to create something on a larger scale.”

In 1993, Ford City lost its massive PPG plate-glass factory after years of the company stripping jobs and lowering production. To replace that 200-acre facility, the borough was able to obtain $12 million in federal and state funds, as well as private investment, to construct a 70,000-square-foot business incubator.

But the project didn’t go as initially planned; one original tenant went bankrupt, and Ford City was eventually forced to foreclose on the property. Even after the boost from private investors and the federal and state government, Ford City had still fallen victim to the narrative so common to Western Pennsylvania company towns: When the company left, the town failed to return to its peak vitality. And in addition to losing the business-incubator project, and being ridiculed by politicians for its failure, Ford City’s poverty, population decline and drug problems have only worsened. In 2015, Ford City’s poverty rate was at 23 percent, up from 13 percent in 2009.

Mains, a former U.S. deputy assistant secretary for economic development in the George W. Bush administration, believes that if the sabotage he alleges is revealed, the town can reclaim some of its former glory. However, there’s little to no evidence to support his claims, and the story of the project’s downfall has already been covered extensively by local and regional media outlets.

David Croyle, the editor of the Kittanning Paper, a small independent newspaper in Armstrong County, has been covering Ford City for years. Croyle says Mains has a long history of community organizing, but can sometimes get carried away. He says Mains is “truly a visionary, but he is a loose cannon.” Still, Mains’ heart seems to be in the right place; he’s passionate about his town, even though it has declined for decades, and attempts to better it have so far failed.

But despite its past struggles and growing problems, many in Ford City remain optimistic, including a young borough councilor named Tyson Klukan. “You need optimism, but you also need energy,” says Klukan. “This is not the PPG era anymore. You can’t forget the past, but you have to brand for the future.”

What lies in store for Ford City might prove a template for the future of Western Pennsylvania’s deteriorating rural towns. President Donald Trump has said towns like these were an example of “American carnage” and their residents were “the forgotten Americans.” Can they come back or will they continue to decline? For Ford City, at least, the future still remains uncertain.

At its peak in 1930, Ford City had more than 6,100 residents. Its success was driven mainly by the growth of Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, now called PPG. “When PPG was at its height it had 5,000 employees,” says Mains. “It was designated the largest plate-glass company in the world.”

John B. Ford, one of PPG’s founders, enabled the company to reach these heights by building a compact and efficient town around the factory in 1887. In an area of less than one square mile, tidy houses were crammed on narrow blocks, a handsome central park provided workers with green space, and a small business district supplied residents with bars, restaurants and shops. It was an ideal company town.

People flocked from across the world to work at PPG and live in Ford City. Germans, Poles, Italians, Slovaks and African Americans from the South all worked at PPG; many built churches and started social clubs. Other companies, like Eljer Plumbing, which became one of the world’s largest plumbing-equipment suppliers, also moved in during the town’s heyday.

Towns like Ford City were popping up all over the region. There are at least a dozen small towns throughout Western Pennsylvania that were specifically created to house workers at factories, and scores more towns that were propped up thanks to one or two large industrial facilities. All of them experienced booming population growth in the early 1900s (Ford City more than quadrupled its population between 1890 and 1930), but that growth started to slow after the Great Depression, in the 1930s. And over the decades, as technology improved and owners looked to make factories more efficient, companies decreased the number of workers, and towns began experiencing decades-long population decline.

Eventually, the companies went under or left the towns they started, either taking operations overseas or to other parts of the U.S., usually where labor was cheaper. In 1993, PPG closed up operations in Ford City.

“When I was a growing up, there were still 2,000 employees at PPG,” says Mains, who is in his 60s. “And then for a generation, from 1993 on, all they saw was a rusted building.”

But while many company towns in the region lost their company and failed to find a viable replacement, Ford City was able to start a huge project just four years after PPG left. Thanks to strong political will from local politicians and then-U.S. Rep. John Murtha (D-Johnstown), as well as great marketing by Mains and others, the small borough raised $12 million in federal, state and private funds (including $5 million from PPG) to redevelop the PPG facility into a business incubator, where small startups could grow into larger companies.

“Every person in every town should realize that if they have an inkling of what can be done, they can do it,” says Mains today. “You might start out as a committee of one, you call a meeting; you get it in the newspaper. In our case we went from a committee of one to $12 million.”

National publications like the Wall Street Journal covered the project, and Mains says it became the poster child for former industrial-site redevelopment. After the project began in the late 1990s, Mains traveled the country singing its praises as part of his job working for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. “It rolled me into this role that I was having to do for communities across the nation,” says Mains. “I was having to speak about Ford City’s model all over the country.”

Ford City, which was managing the project through a community-development corporation, completed it in 2004 and attracted as tenants a high-tech manufacturing company, Caracal, and a window-shade company, OEM Shades. But Caracal, which was fairly new, began experiencing financial problems and had trouble paying its rent. Without that income, the community-development corporation went bankrupt in 2008; Caracal followed in 2009, the same year the borough was forced to foreclose on the property.

All of this hit Mains hard. “I think what happened was, when they saw us lose the [millions of dollars in funding], there was a lot of confidence lost in the council,” says Mains. “The town was being ridiculed.”

On top of the loss of the project, Ford City was slapped with a $580,000 fine by the U.S. Economic Development Administration for foreclosing on the property too soon, violating the EDA grant.

And in 2015, Ford City was reminded of this failure when U.S. Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) derided the town by including the project’s failure in his 2015 “Wastebook,” calling the project a “Bankrupt Boondoggle.”

The Wastebook report reads: “Once touted as a ‘success story’ of government investment, ‘a catastrophic financial disaster’ could be the final result of millions of public dollars poured into an economic development project in a Pennsylvania municipality.”

“Sometimes people say your best days are behind. I really believe our best days are ahead.”

tweet this

As a result, Mains began to float the theory that the project was sabotaged. Mains believes the project failed thanks to a few actors prioritizing their self-interests over those of Ford City.

But Hobie Webster of the Pittsburgh law firm Weiss Burkardt Kramer, who investigated the case on behalf of Mains, says the firm found no proof of this claim.

“[Mains] wants to say to the world that there are people responsible out there that caused the downfall of this project,” says Webster. “I did suspect that at the time, but I wasn’t able to prove that, and my job as an attorney is to produce a case that could help them out.”

One thing Webster did find peculiar was that Ray Boarts, who sat on Ford City’s community-development corporation board during the project, did have a financial investment in Caracal, a possible conflict of interest. Webster says he never found documents showing whether Boarts disclosed his status to the board, but he also couldn’t prove when exactly Boarts invested in the company. Since Boarts could have invested in the company well after it moved into the former PPG site, says Webster, there was no way to prove the investment was below-board. (Boarts passed away earlier this year.)

Additionally, Webster says, before his firm started looking into the case, the FBI conducted raids of the Ford City and Armstrong County agencies that were involved in the failed project. He says “there was enough smoke” that a federal grand jury convened over the matter. But the grand jury didn’t find anything to produce charges.

“I did not find any kind of self-dealing,” says Webster. “What I found was a project that never should have been leveraged the way it was. They were so desperate for clients. They signed up with Caracal, who didn’t have a long history, they had just been created. The recession hit and Caracal went under.”

Webster says Ford City may have been a little overly ambitious with the development project, and the timing, as with Caracal, was not in its favor.

“It’s not the story that [Mains] thinks it is,” says Webster. “People always suspect people of bad dealings. When you look at the timeline of when this project collapsed, it mirrors the beginning of the recession. … In 2002, 2004, 2006, Ford City was taking out all these loans to develop the property. They were not aware the bottom was going to fall out of the global economy.”

Regardless of what exactly killed the project, Mains says it’s crucial to “clear the town’s name,” and show that Ford City can be trusted with big projects again. Mains has some ambitious ideas. He wants to turn the old Ford City High School building into a “glass college,” where student artisans can perfect their glass-making skills. And he wants to re-establish the business incubator, which he says will create a positive ripple effect from small-business growth.

While his focus on the failed project might seem misguided, Mains says it will take people with his passion to revitalize Ford City.

“Somebody has to do it,” says Mains when asked why he has been fighting for Ford City for decades. “And usually if there is one person to get it going, there will be other people to join, I guarantee. This is our second chance at our second chance. Every community should realize this. If it doesn’t proceed the way you want, go again. We will get there in Ford City. Sometimes people say your best days are behind. I really believe our best days are ahead.”

Webster feels for Mains, but says Mains might want to consider other options for helping Ford City. “I am sympathetic to [Mains], he wants to save his town,” says Webster. “But it is not going to happen the way he wants it to happen.”

On June 6, inside the Family Life studios in Kittanning borough, just upriver from Ford City, David Croyle, editor of the Kittanning Paper, prepares to go on air for his Talk of the Town radio show on WTYM, Hometown Radio. An upholstered red armchair sits next to his small desk, as Croyle scrambles from room to room to check the sound levels, the lighting and his computer. A few assistants help him set up, careful not to disturb the Bible study in an adjoining room.

For his show, Croyle picks a topic each week and responds to calls and texts from listeners; this week, Pittsburgh City Paper was invited to hear listeners weigh in on Ford City and share their opinions on Armstrong County and the future of its economy.

The average Armstrong County resident appears torn on who is exactly to blame for the decline of Ford City. One listener texted that he worked at PPG for 32 years and claimed “corporate greed shut down the plant.” A caller said the local government made too many mistakes, which caused the town’s downfall. And another after that said that organized labor was too heavily involved in decisions at PPG and Eljer, which pushed the companies out of the area.

But one thing many listeners seemed to agree on was that the area is hungry for some positive change. One listener texted, “We live in an affordable area [with] a huge green area. People, for the most part, speak to one another. The crime rate is low compared to other bigger areas. … And PPG and Eljer closed; we need to look forward, not backwards. Times changed.”

Croyle, in an earlier interview with CP, said many in the area put a positive spin on the benefits of rural town life. He also says that many in the area are selective about how exactly to get the change they desire.

“If you ask the average person what is the matter with Kittanning, what’s the matter with Ford City, what is the matter with our small towns, they will say, ‘Well there is nothing here,’” says Croyle. “‘We need business. We need a Burger King, for heaven’s sake.’ But they don’t understand that these things come as a response to population growth. … But they might say, ‘Oh, we don’t want that because that might attract undesirable people.’ But people on welfare and on the other end of the socio-economic spectrum will buy burgers and buy products.”

Armstrong County and Ford City, like many Southwestern Pennsylvania areas, are still experiencing decades-long population decline. Since 1980, the county has lost 15 percent of its population, and Ford City’s population has dropped 28 percent.

The area is also not seeing any of the positive international migration that is helping to stem the tide of population loss in places like Allegheny County. From 2010 to 2016, Armstrong County saw a positive net international migration of only 33 people, bringing the total foreign-born population to about 400 out of the county’s 68,000 residents. Ford City wasn’t home to any of them: Census figures indicate that the town doesn’t have a single foreign-born resident.

But contrary to how rural Southwestern Pennsylvania areas are portrayed in the media, Croyle believes Armstrong County would welcome immigrants. “Go back pre-PPG,” says Croyle. “There are people that came over from Poland and all these different places. They settled in pockets of Ford City. I believe we are accepting, because immigrants would be bringing that element they want. They are bringing businesses.”

Marc Mantini, a Ford City Borough councilor and former Ford City mayor, echoes this sentiment. He says there is no resentment towards immigrants in the town. He also agrees that losing the town’s population is its biggest obstacle.

“Our main problem is depopulation. We [thought] this new school would bring in jobs, but it hasn’t,” says Mantini of a recent effort to consolidate high schools in the county. “There is a general malaise that is coming over this community.”

Creating positive change without population growth is the paradox facing Armstrong County, says Croyle. County residents want the amenities suburban and urban communities have, but are forced to leave the county to find them. “If you want to go to any of the major chain restaurants, you have to drive 30 minutes away,” says Croyle. “Our population cannot support that chain. In order to get the products and services they want, they have to go someplace else.”

Longtime Ford City resident Caroline Hassa agrees that this is a problem. She too leaves Ford City and Armstrong County to do most of her shopping, and thus spends some of her disposable income outside the community she wants to see prosper. “I want to shop local, I want to support my local people,” says Hassa. “I don’t want to have to travel.” Ford City lacks a grocery store in the walkable town’s business district and the number of shops, bars and restaurants has been dwindling for decades.

Hassa says the former accessibility of the town was one of the things that made it desirable. “That is how it used to be,” says Hassa. “It was like one-stop shopping, it was all Downtown. You had to go to different shops, but you didn’t drive to the mall.”

But Hassa says things are changing in Ford City, as the town is starting to participate in trends more common in bigger cities. She says the borough sponsors a First Friday festival each month, bringing in local food trucks and vendors, and a weekly farmers market lets residents purchase products from small local businesses. Hassa also says a microbrewery is set to move into Ford City’s business district soon. She says through cooperation, the borough can rebound.

“If the whole town comes together, we might be able to do something,” says Hassa. “We haven’t had that spirit for a long time, but it is coming back. Ford City is a special town, it is a diamond in the rough. If we can progress in these areas, then we can come back.”

In Ford City Memorial Park is a sign commemorating four important historical landmarks of the small borough: the Ford City Bridge, the PPG plate-glass factory, the Eljer Plumbing factory and Ford City High School. The only one of the four left standing is Ford City High, and the Armstrong County School District is proposing its demolition.

Don Mains is in a mad dash to try to save the school, claiming the demolition process hasn’t been adequately vetted by the public (there has been one public meeting held in Ford City, but none conducted by the school district). “Ford City High School will be demolished unless we secure an injunction to force the back-room politics out into the open and further enforce the will of the people,” wrote Mains in a June 19 email to CP, one of many he sent in recent weeks. Mains wants to preserve the school and try to turn it into a glass college for student artisans, even though current proposals suggest it as a location for senior housing, modeled after the popular Kittanning Cottages, located up the river.

Mains has often mentioned that achieving his visions for improving the town would be easier if Democratic U.S. Congressman Murtha were still representing Ford City. In a voicemail to CP, Mains said, “Congressman Murtha was an example of why not to have term limits. He was a consummate man of bringing money into the district, money that would not have come here without him.”

Murtha, who died in 2010, represented Ford City for decades and was crucial in getting funding for the business-incubator project and just about everything else.

Jerry Shuster, a KDKA political analyst, Kittanning borough councilor and longtime Murtha supporter, says that when Ford City started seeing its steepest decline, in the 1990s, it was Murtha who helped the town stay afloat.

“Ford City lost PPG glass and Eljer; we were in bad shape economically,” says Shuster. “When everyone else was at 4 [percent] to 5 percent unemployment, we were at 12 percent. It was John Murtha who kept it from death’s door. I mean it. He had the power and fortunately enough for us, when he wielded it, we were the benefactors.”

Shuster says that Murtha was once referred to by Newsweek as the 13th most powerful politician in the country. U.S. Murtha was also called the King of Pork for his unapologetic ability to funnel money into his district, earning him criticism from Esquire magazine, which in 2008 called him one of the 10 worst members of Congress.

And Murtha’s unmatched ability to bring in money may have kept the region from learning to take care of itself. According to the Kittanning Paper, before 2016, Armstrong County went without a comprehensive economic development plan for 25 years.

But Shuster defends Murtha’s influence. “I would be the first to admit that Murtha kind of gave us the crutch to hang onto while we started to become more innovative,” says Shuster. “And it’s taken a while, but we are finally finding a way to do it. There are still some good thinkers in the area and lots of people working hard to overcome that. He just helped us spread the wealth a little bit, while we learned to deal with our problems.”

And Shuster says that even if someone as aggressive in getting funds as Murtha were still representing Ford City (the town is currently represented by big-government critic Mike Kelly, a Republican from Butler), the role of the federal government has changed. He points out that the locks and dams along 14 miles of the Allegheny River in Armstrong County were always funded under Murtha, but now they are run by a nonprofit and open only to weekend traffic.

“In Murtha’s day, the money was a little easy to come by. That changed in the Reagan and even the Clinton years,” says Shuster. “Each time a new budget came out, those giveaway programs were reduced more and more. … Where we need the money the most, they are taking it away.”

Ironically, Shuster says, President Donald Trump remains popular in the region, even though Trump is now proposing cutting the federal programs that provide much-needed assistance to Ford City and Armstrong County.

Ford City voted for Trump over rival Hillary Clinton by 19 percentage points, and Armstrong County as a whole voted for Trump with 74 percent of its vote, the second highest among Pennsylvania counties with more than 50,000 residents. (Croyle also says the region’s decline helped to lead voters to Trump, but attributes voters’ overwhelming approval of Trump to his stance on gun rights, since Armstrong County has the highest gun-ownership rate of any county in the state).

In his inaugural address, Trump characterized places like Ford City as victims of “American carnage,” thanks to its shuttered factories, rampant blight and increasing drug issues. (In 2015, Armstrong County had the second highest opioid overdose rate of any Pennsylvania county, at 43.3 per 100,000 residents.)

But while Ford City voters overwhelmingly backed Trump, conversations with Ford City residents, business leaders and politicians rarely focused on the themes of “American carnage.” Shuster rejects Trump’s assessment, and says Ford City and Armstrong County residents are hopeful.

“I don’t believe it at all,” says Shuster. “I think we are far ahead. We still maintain our values, and we still have the same problem of opioids that a lot of places have. But beyond that, we have a better take on what the future can hold for us, and we are ready for it.”

On a warm June evening, Bob Marley is playing on the jukebox inside Stanley’s Bar and Grill near the southern edge of Ford City. The bar is filling with customers looking to enjoy a beer or a conversation, or to dance to some tunes. Tyson Klukan, a 25-year-old borough councilor, is about to dig into his hot-sausage sandwich (everyone in Ford City swears these are the best in the region); a frosty mug of beer awaits him to wash it down.

Klukan says there is a new movement already underway to improve Ford City, and one that is leaving the failure of the business-incubator project and the town’s industrial past in its rear-view mirror. He was elected in 2015, along with three other new councilors, and says this wave of new blood has injected a sense of hope.

“I see it as an opportunity,” says Klukan. “We once had a thriving town and then it all went away. But now we have all this land along the Allegheny River. It’s a big opportunity.”

Klukan says the borough is looking to modernize and update its master plan and rezone large industrial swaths of the borough to attract new development. He sees Ford City, with its cheap rent, business-friendly attitude and compact layout, as a haven for small businesses. The borough also owns a 42-acre site that has been environmentally remediated and is ready for development; Klukan hopes the site will be used for many purposes, whether riverfront condos or industry.

The borough council also recently authorized a $116,000 payment to the Economic Development Authority, paying the fine originally levied in 2015 and eliminating any connection to the business-incubator project. The building is now owned by BelleFlex, a disk-spring manufacturer; OEM Shades still leases space there.

Klukan, along with almost everyone that CP interviewed for this story, believes Ford City can grow if it can maximize its tourism potential. The county has a 30-mile paved bike trail that runs along the Allegheny River from Ford City north to East Brady. Crooked Creek Lake Recreation Area is just a 10-minute drive from Ford City, and offers fishing, boating and trails. Just a few miles south of there, Leechburg has kayaking on the Kiski River. Klukan believes that as the Pittsburgh region grows, more people will realize Ford City has small-town charm to offer day-trippers.

Likewise, Kathy Bartuccio, a fellow borough councilor, runs Ford City’s farmers market and says it has brought a bit of life into the business district. “I think it does bring some people in,” says Bartuccio. “They hate when they miss it, the farmers market.”

But even with the potential upsides, there is still a long way to go. Klukan admits that the town must find a way to tackle its blight, which has only gotten worse. (From 2010 to 2015, Ford City gained more than 100 vacant properties, bringing its total to 266.) And Bartuccio says blight becomes increasingly difficult to combat, because each year there are fewer homeowners looking to redevelop homes in Ford City.

“I think the town is still declining,” says Bartuccio. “We have a large amount of renters, about 47 percent of Ford City.”

Still, Michael Coonley of the Armstrong County Department of Economic Development says a focus on the positive can help Ford City rebound. “Just because you build it doesn’t mean they will come. But I think Ford City is taking an active, aggressive role to make sure people are invested,” says Coonley. “I think sometimes we can be our own worst enemies. If you see something every day, you tend to forget the good things. People can just focus on the negative aspects. We have to try to emphasize those good points more than we have.”

But while this positive attitude will surely encourage some, this isn’t the first time a theme of comeback has been sold about Ford City. In 1999, a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette feature story showcased the decline of the borough, a failed attempt to redevelop some former industrial facilities, and the potential of the business-incubator project. “This may be our last chance to see if we can make it,” said Mains to the Post-Gazette in 1999.

Hobie Webster, the Pittsburgh-based attorney, says towns like Ford City are up against systemic economic forces that give rural areas little chance to succeed.

“When you have these towns that rely on industry and manufacturing, and you don’t have any strategies to keep those jobs in the country,” says Webster, “and instead you have a system focused on international trade and maximizing corporate profits, you create all these avenues to move these jobs someplace else.”

As a result of companies leaving the towns they started, the void of wealth only continues to increase. And as businesses and investment continue to leave, it becomes less attractive for people to remain or start businesses, or for newcomers to move in. And these problems compound each other, because rural Americans live far from the dynamism of big cities, making it harder for them to access the jobs and capital of those economies.

Even though President Trump’s description of these towns as “American carnage” might not jibe with how the residents there view themselves, he was right about one thing. Residents of rural declining towns are “forgotten Americans,” as Trump said throughout his 2016 presidential campaign. They aren’t the only forgotten ones, but they have indeed been left behind. And they’re being left behind because they refuse to abandon their homes — something Webster says we should respect about them, not shame them for.

“People aren’t going to leave because if they leave, they lose their town,” says Webster. “There is something admirable about people loving their town that much.”