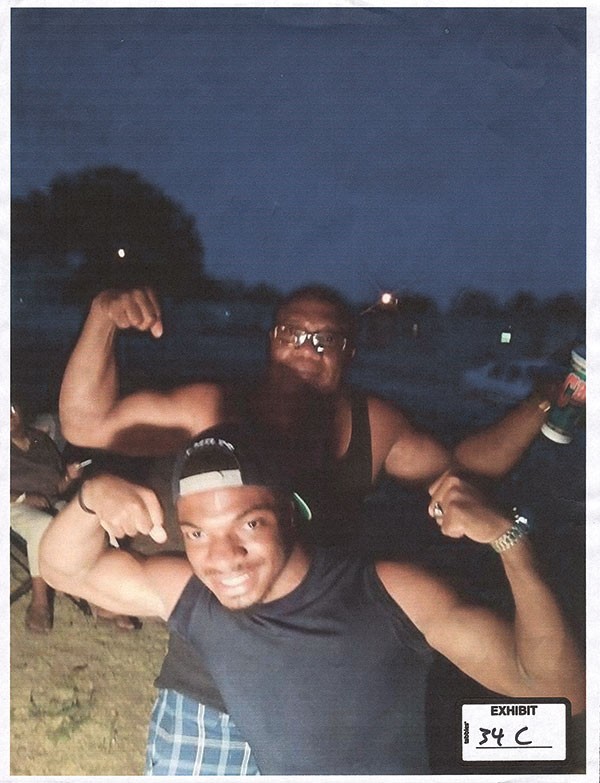

It seemed innocuous enough. Wearing a dark-blue tank top and backward baseball cap, Jordan Miles is raising his arms up to his head and flexing his biceps, grinning through a patchy beard and mustache. His father, grasping a cup in his left hand, is standing in the background in an identical stance.

They're posing for a photo — one Miles thought nothing of sharing on his Facebook page. But that picture's meaning would be forever altered, eventually morphing into Exhibit 34 C: evidence that would be used to try and convince a jury that Miles was a physical threat against the three Pittsburgh police officers whom he'd accused of leaving him bruised and bloodied before falsely arresting him.

That photo was just one of several taken from social media that were introduced in both of Miles' civil trials against the city and three of its officers. Some of them were profile pictures, up for grabs to anyone with an Internet connection.

Not the photo with his dad.

"They had to have been my [Facebook] friend to see it," says Miles, now 22. "I was shocked that they were able to go on my page."

Whether Miles should have expected photos he posted of himself online to remain private is a complicated question — and the legality of using social media to gather evidence is constantly evolving. But documents recently obtained under the state's right-to-know law show that the city hired outside investigators to collect information about Miles on social media in ways that could have violated ethics rules, including creating fake profiles or trying to reach him without permission from his lawyers.

The documents show that after Miles sued the city and the officers who beat and arrested him in 2010, the city hired CSI Corporate Security and Investigations to gather information about him. And while cities frequently investigate people who sue them, an invoice shows the city was billed for creating a social-media profile and email address not only for "monitoring of social networking profiles" but also to "connect" with Miles.

"I can't imagine they set up an email account and said, ‘Hi, we're an investigative agency for the city and want to ask you some questions,'" says Steven Baicker-McKee, a law professor at Duquesne University with expertise in civil procedure. "It would be improper to go around a party's lawyer to get in touch directly through some kind of social-media outreach."

Still, the documents don't detail exactly what information was collected or whether the profile used to connect with Miles was deliberately misleading. Neither CSI nor the city would elaborate.

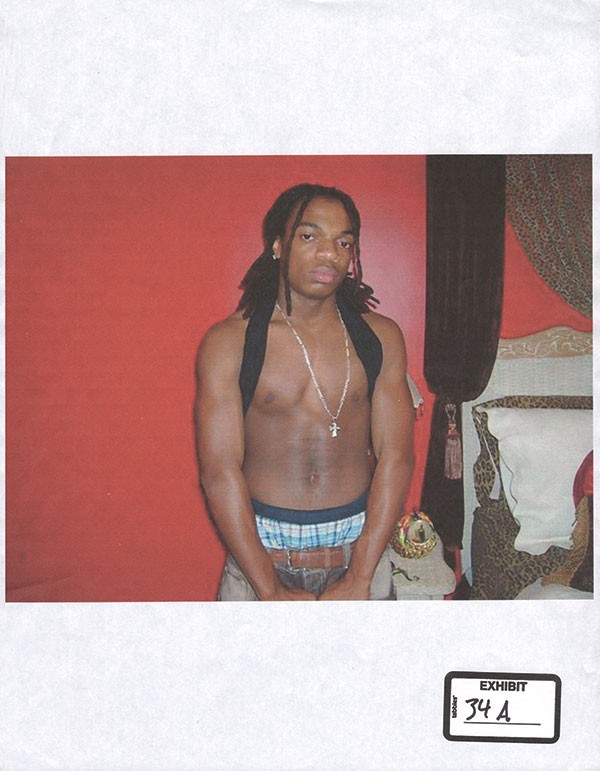

Miles acknowledges that some of the shirtless, muscle-flexing photos introduced at trial had been public-profile pictures, viewable by anyone. And he admits accepting lots of friend requests from people he didn't know — he was inundated after his case drew national headlines.

But whether the content Miles shares only with his Facebook friends should have been included at trial is debatable. Opinions differ, for instance, on whether friending someone using a fake profile on Facebook is the same as creating a fake profile to view someone's public LinkedIn page.

"That's how granular it gets," says Hanni Fakhoury, a lawyer with the non-profit Electronic Frontier Foundation, which focuses on civil-liberties issues related to technology.

For Ethan Wall, a social-media legal expert who teaches at Nova Southeastern University, in Florida, the documents are suspicious.

If "an investigator is creating a fake profile to connect with Miles, [that] raises some serious red flags about whether or not the investigator may have taken steps to access Miles' content in a way that might violate bar ethics rules."

Ever since 2010, when Miles was confronted by Pittsburgh officers David Sisak, Michael Saldutte and Richard Ewing, critical facts about what happened have been disputed.

As Miles walked to his grandmother's house on a cold January night, the officers claimed Miles was acting suspiciously and tried to flee when they hailed him. What happened next has been the subject of two federal civil lawsuits. Miles claimed the officers jumped him without identifying themselves, while the officers say they alerted Miles that they were police officers, and feared that a bulge in Miles' jacket might be a gun, though no gun was ever recovered.

No one disputes that social-media evidence was gathered to frame Miles as a threat to the police.

"Jordan Miles was ripped," Jim Wymard, Sisak's attorney, said during the first trial. "You saw the MySpace page. He called himself Bulky J. He wanted to be bulky!"

That characterization still sticks with Miles.

"All I really do is work my arms because that's the main attraction," he says. "They were trying to paint a picture like I was some Incredible Hulk. That's not who I am."

In August 2012, a jury found the officers innocent of malicious prosecution, but deadlocked on whether the officers erroneously arrested Miles or used excessive force. This March, a separate jury awarded Miles around $119,000 for false arrest, but said the officers did not use excessive force. An appeal from Miles is expected.

It's not clear what effect the defense's characterization of Miles through these photos had on the jury; lawyers for the police officers said their case didn't hinge on them. But while it's not uncommon to introduce evidence gathered from social media, legal experts say the language on the invoice from CSI, the company that investigated Miles, could suggest two separate ethical problems.

One is the use of deceptive tactics to gather information by creating a fake social-media account. The other is trying to communicate with Miles on social media without his lawyer's permission, even if there had been no misrepresentation.

The part of the invoice in question is dated Nov. 29, 2011, and states: "Create e-mail address and social media networking profile in attempt to connect with Miles." The invoice lists others involved in the case as well as unnamed "associates" whom the company also apparently tried to reach online.

"My initial instinct is it sounds not kosher," says the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Fakhoury. "You don't want to trick people into saying or doing things or turning over information under false pretenses," noting the invoice does not definitively show that CSI investigators used deception.

Miles says he doesn't remember getting any suspicious emails, but he accepted plenty of friend requests from people he didn't know because there were a lot of people "who wanted to show their sympathy for me."

But even if investigators didn't misrepresent who they were online, just sending a friend request has been interpreted by some courts to constitute improper contact, Fakhoury says. "The idea is we don't want people to meddle with the attorney-client relationship."

According to a formal opinion issued by the Pennsylvania Bar Association, "attorneys may not ethically contact a represented person through a social networking site [...] regardless of the method of communication." The same opinion prohibits deceptive practices including having someone else who won't be recognized make the social-media contact — even if they are honest about who they are. In other words, it would be unethical for a lawyer to ask a friend of a friend to contact Miles in an attempt to gather information, even if there was no deception.

CSI maintains its investigators did not violate ethics rules.

While the company has a history of conducting investigations for the city, CEO Louis Gentile says the city isn't a major client. City Paper reported last month that the Monaca-based company was hired to investigate an incident last summer in which a teenage girl was punched and arrested by an officer at PrideFest. CSI determined that the officer did not use excessive force.

On the Miles case, Gentile says that CSI wasn't the lead agency, but "we may have done some background." The city paid CSI about $2,000 for services related to the Miles case, including $93.75 for social-media-related research.

Asked about the company's use of social media to investigate Miles, Gentile says his investigators would "never attempt to contact a plaintiff without a lawyer's permission," and that "whatever we do goes through two attorneys on staff. We don't do anything that's ethically dubious or illegal."

Asked about the Miles invoice, Gentile wrote in an email: "that was an attempt to track public social-media postings and any public interactions with each other." He declined to answer specific questions about why the invoice says there was an attempt to "connect with Miles"; why the invoice distinguishes between "monitoring" social media and "connect[ing]" with Miles, and whether that means his company tried to "friend" him or create a fake profile.

"I believe that everyone should be perfectly transparent," Gentile says. But "there's a time I have to defer to the client."

The city law department, the entity that would bear ultimate responsibility for the conduct of the investigators it hired, declined to comment for this story.

But according to Randy Torgerson, a private investigator of 14 years and president of the United States Association of Professional Investigators, it's plausible that the city wasn't directly supervising the investigators.

"It's highly possible the city did not know," Torgerson says. "No investigator lays out the minute details of everything they're going to do for the client."

Ignorance of specific investigative tactics, however, wouldn't absolve lawyers involved in the case of responsibility. "An attorney can't say, ‘I just had no idea [investigators] violated these rules,'" says Wall, a social-media legal expert who has written extensively on the topic. Lawyers, he adds, are responsible for staying on top of ethics opinions that could affect their casework.

In general, Torgerson says, it's "pretty common" for investigators to friend people on social media as a way of gaining access. He doesn't think that necessarily crosses an ethical line.

"The best place to find how somebody is — is what they tell their friends, what they tell anybody else outside the courtroom."

Still, using social media while acting on behalf of a municipality to befriend someone like Miles — who had already retained a lawyer — could be different.

"You're trying to defend a government entity – you want to be beyond reproach."

In both trials, the photos were controversial — and lawyers from two separate legal teams bristled at their use. But no one questioned whether the photos were gathered ethically.

"We filed motions and argued the photos were irrelevant," says Kerry Lewis, Miles' lawyer in the first trial. "As far as being obtained improperly by the city, we had no information whatsoever to rely on as far as to try to have them stricken." If investigators obtained the photos by creating a fake account, "they didn't tell us at the first trial," he says.

"If it was improper and it was used in a court proceeding, that should be brought to the attention of the court even now."

Joel Sansone, the lawyer who represented Miles in the second trial, sounded a similar note, saying he never knew specifically how the photos were collected.

But it wasn't just Miles' lawyers who appeared not to know the details — Bryan Campbell and Wymard, both lawyers for the officers, also said they weren't sure how investigators acted on social media.

"There was no distinction made" about how the photos were gathered, Campbell says. He points out that some of the photos of Miles were gathered from profile pictures, something Miles acknowledged in a recent interview.

"These had passed muster with four separate attorneys," Campbell adds. "There was no objection to this at trial."

All of the lawyers involved in the case who commented for this story, including Campbell, Wymard, Sansone and Lewis, say they are unfamiliar with all of the mechanics of Facebook.

For his part, Miles never seemed to make a big deal about it. He never told his lawyers that the photos might have been gathered from parts of his Facebook page that weren't publicly available. "I wouldn't have known to ask, [and] Jordan probably wouldn't have known to attach enough importance to the matter," says Sansone, Miles' lawyer. "There would have been quite a rhubarb over that."

But impropriety could have been difficult to prove: It's possible that investigators got the photos without using deceptive tactics or ever having sent a friend request — a friend could have simply turned them over. It's also possible that the privacy settings on Miles' Facebook account were more porous than he thought.

Wymard, who represented one of the officers, says that even if investigators did create an account to get Miles to accept a friend request, that wouldn't have bothered him: "It's an interesting investigative tactic. It's not like opening their mail."

Wymard added that it wouldn't constitute meaningful contact with a represented party — a violation of ethics rules — "because you're not taking a statement from him."

The Electronic Frontier Foundation's Fakhoury disputes that. "He's flat wrong — deception is absolutely the problem," he says, adding, "friending a person is contact."

The practical effect of using photos that might have been gathered unethically isn't obvious.

While violations of ethics rules could lead to anything from a reprimand to disbarment of lawyers involved in the case, experts say it's possible a judge would have allowed the photos to be introduced as evidence.

"The judge has a lot of discretion in what he'll consider or not consider," Wall says. "In my experience as a litigator, if someone obtains evidence by violating ethical rules, [the judge] would be well within his discretion" not to allow that evidence.

In extreme cases, "You can move for a new trial and say there was misconduct," adds Fakhoury. "But it'd be tough."

He says cases like Miles' will only become more common, forcing lawyers and the investigators they hire to reckon with the evolving ethics of gathering information on social media.

"There are only a few ethics decisions on this," Fakhoury says. "I think you're going to see the American Bar Association weigh in."

"That's the grey area we're in — in terms of social media and technology," Wall adds. "It's changing faster than the law can catch up. It really is the wild, wild west."