When the Sto-Rox School District ran out of money for paper in February 2020, local businesses and residents poured into a GoFundMe drive to meet the need.

That need was just one of many, most of which couldn’t be solved with simple crowdfunding. Two years later, the state stepped in with a financial recovery plan outlining teacher retirement incentives, higher healthcare contributions, and local tax raises. Stll, even those leading the charge acknowledged the path ahead looked steep.

But a Commonwealth Court ruling on Pennsylvania school funding, announced last week, means that, at least in theory, the burden that’s long fallen on struggling communities like Sto-Rox now rests more broadly on the state legislature.

The decision comes nearly 10 years after petitioners from six ailing school districts challenged whether state officials were living up to their constitutional obligations to maintain and support “a thorough and efficient system of public education.”

Although none of the original petitioners were based in Allegheny County, economic and academic disparities are rife across its 43 public school districts, and the ruling could spell welcome news for those facing setbacks.

“Allegheny County as a whole has some of the widest disparities in the state,” Jackie Foor, executive director of Consortium for Public Education, tells Pittsburgh City Paper. “We are excited that Judge [Renée Cohn] Jubelirer has recognized that [education] really is a fundamental right.”

Lawmakers can still appeal the decision, but, even if it stands, its full impact remains far from clear.

While the petition was launched around a push for equal funding, Jubelirer found the General Assembly’s obligations also extend to students’ academic, social, and civic outcomes.

“The appropriate measure,” writes Jubelirer, “is whether every student is receiving a meaningful opportunity to succeed academically, socially, and civically, which requires that all students have access to a comprehensive, effective, and contemporary system of public education.”

Measuring success

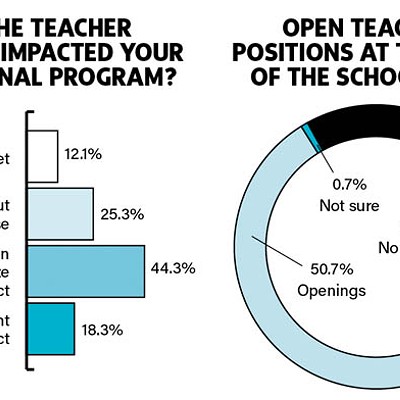

To determine how a school measures up, Jubelirer names five “inputs” — funding, staffing, curricula, facilities, and “instrumentalities of learning.”

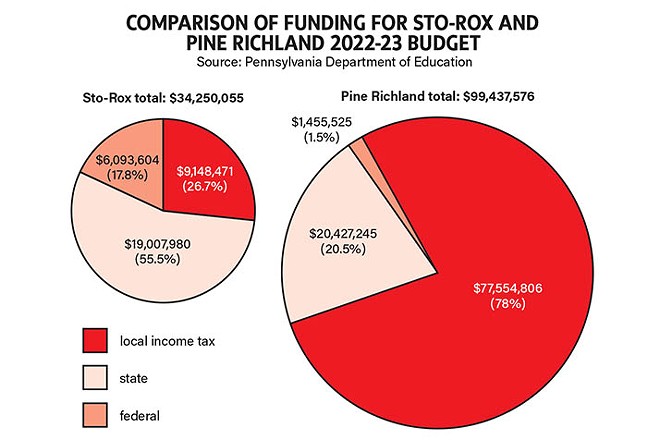

Generally, Jubelirer notes, more than half of a district’s funding comes from local sources, disadvantaging low-wealth communities that rely on weak tax bases.

“What the Court’s findings illustrate is local control by the districts is largely illusory,” she writes. “Low-wealth districts cannot generate enough revenue to meet the needs of their students, and the pot of money on which Legislative Respondents allege they sit is not truly disposable income.”

That lack of cash exacerbates the other issues. The amount of funding available to districts also impacts their ability to provide for the other inputs, like staffing, curricula, and after-school programming, Jubelirer says.

While high-wealth districts boast scores of extracurricular activities – arts classes and other electives, after school tutoring, and programs for college and career readiness, including Advanced Placement classes — Jubelirer finds that those resources do not exist, or are entirely inadequate in many low-wealth districts. In one example, a teacher in the William Penn School District told the court that her district can’t afford to give her 25 kindergarteners more than 15 minutes of recess a day.

Deficiencies in material resources, whether it be school buildings, computer technology, or up-to-date textbooks, are points of high concern in the ruling.

Jubelirer cites testimony from students in some schools being taught in classrooms where the sky is visible through holes in the roof, and, in another instance, where children are reportedly learning from history textbooks so old they name Bill Clinton as the current U.S. President.

“The evidence demonstrates that low-wealth districts … which struggle to raise enough revenue through local taxes to cover the greater needs of their students, lack the inputs that are essential elements of a thorough and efficient system of public education.”

While acknowledging limitations of standardized testing, Jubelirer cites a string of “outputs” to evaluate the funding-driven “inputs” she cites. They are: state assessments (in Pennsylvania, the PSSAs and Keystones), PVAAS (a measure of academic growth preferred by the Legislative Respondents), national assessments, high school graduation rates, post-secondary enrollment, and racial disparities. These metrics, she says, help gauge whether every student “is receiving a meaningful opportunity to succeed.”

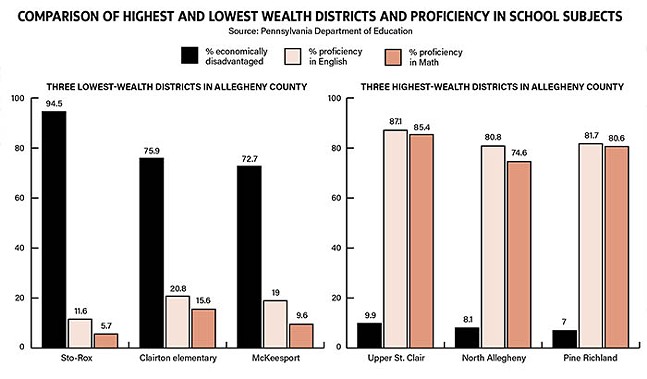

Summing up the inputs and outputs, Jubelirer points to “consistent gaps” between high- and low-wealth districts. The conclusion that not every student in Pennsylvania receives a meaningful opportunity to succeed, she writes, is “inescapable.”

Local implications

The reports of rampant disparity underscoring Jubelirer’s 800-page conclusion are mirrored across school districts in Allegheny County.

Just a year before the Sto-Rox paper crisis, middle schoolers at the neighboring Montour District celebrated the opening of the country’s first public school artificial intelligence lab.

In the Mon Valley, a 2020 report on segregation in American schools found that the districts of Clairton City and West Jefferson Hills, which share a border, represent the country’s ninth-greatest divide among neighboring districts.

Local officials say that they’re quietly optimistic the ruling could lead to a narrowing of these extremities, while noting the many remaining uncertainties.

“Now is the time for Pennsylvania to stand strong and demand a funding formula that works for all students,” Megan Van Fossan, superintendent at Sto-Rox School District, says in a statement. “We need a funding formula based on our students' actual needs. Our kids at Sto-Rox are amazing but they do not have the same opportunities as students in well-funded districts.”

John Zahorchak, business manager at the Penn Hills District, tells City Paper he’d like to see lawmakers get to work in time for the next fiscal year.

“It seems to be a step in the right direction,” Zahorchak says. “At Penn Hills, along with many other urban schools, we have some unique challenges. We look forward to learning more about a system that is fair and equitable for all students.”

Penn Hills wracked up a $15 million deficit in 2015, but has steadily risen back to solvency since entering the state recovery program in 2019, according to reporting from PublicSource. Indicating the kind of difference outside funding can make, the arrival of millions of dollars in COVID relief monies played an important part in the district’s recovery.

But the question of how much struggling schools stand to gain from the Pennsylvania ruling remains unclear.

An appeal from Republican lawmakers could set the clock back many years, warns Ira Weiss, a solicitor representing Pittsburgh Public, Sto-Rox, and several other local school systems. Even without an appeal, Weiss expects years of wrangling between lawmakers, where Democrats maintain a razor-thin majority in the House and Republicans control the Senate.

“It’s far too early to say whether a new system will be devised, and what it’s going to look like,” Weiss tells CP.

“This is the first page in a very long story.”