We all grow up with fairy tales and fables: stories of princes and princesses, the magical and the outlandish, the all-too-real and the out-of-this-world narratives.

But what about the stories we don’t hear, stories that didn’t start to emerge until recently? Ones with Black mermaids or Muslim protagonists? Queer literature or tales featuring disabled persons?

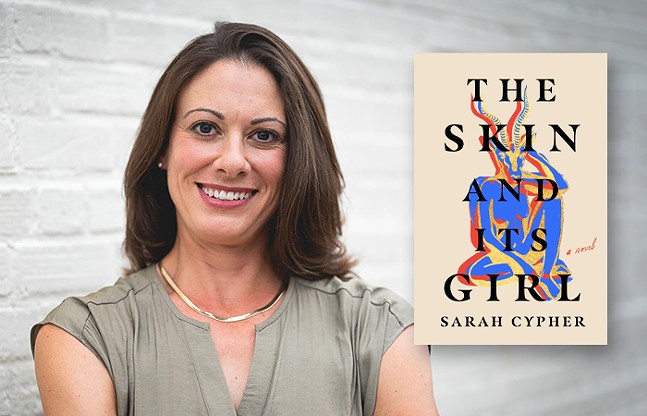

Pittsburgh author Sarah Cypher’s debut novel The Skin and Its Girl serves many purposes. It delivers the kind of queer narrative Cypher never heard growing up. It seeks to rectify the whitewashing of Arab Americans in the U.S., recover and preserve Cypher’s Middle Eastern heritage, and look at parallels in the systemic injustices found in America and Palestine.

“Representation matters,” Cypher tells Pittsburgh City Paper. “I wanted the readers to think about what stories they take for granted and where the gaps exist between what we have language for and what we don’t but still feels true.”

Steeped in magical realism, Cypher’s novel delivers a stirring, lyrical tale of a family through numerous generations and the stories that run through them, beginning with the birth of the Elspeth Noura Rummani, aka Betty Rummani, a queer Palestinian American with cobalt blue skin.

Cypher says she started the novel around 20 years ago. In a very early draft, characters gave birth to a cobalt blue baby. However, she didn’t know what to do with the idea then. Every time the Freeport Area High School graduate tried to explain why the child was blue, the story fell flat.

“The longer I left it as an open question, the more I felt like the novel could explore what I wanted it to explore,” says Cypher.

Then the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon happened, and Cypher began thinking about what it meant to be Arab American in a post-9/11 United States.

“I don’t think of myself as a woman of color, but a lot of my relatives do,” Cypher says. “Post 9/11, I leaned pretty hard into recovering that identity after seeing a lot of people forget it. We owe a lot to the work done in the 20th century to be considered equal. But at the same time, we look at stuff like how the U.S. census still doesn’t have a category for Arab Americans; there’s this kind of whitewashing in America that I was really uncomfortable with. So, in a way, working on The Skin and Its Girl was an intervention in that.”

Cypher finished the draft but could not find an editor at the time, so she put it aside. She picked up The Skin and Its Girl again after joining the Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina, where she received her MFA.

“A lot had changed since I first worked on it; there was a lot more literary magical realism out there being published in English, I was reading a lot more queer literature, and more queer literature was getting published,” says Cypher. “When I finished it at the end of my MFA, I felt it was coming out into a different world from when I first started it.”

The Skin and Its Girl covers over 200 years of history as Rummani visits her late Aunt Nuha’s gravestone. Various family narratives and tales are explored in a stream-of-consciousness fashion, as Rummani decides whether to stay in the U.S. or head abroad with her lover. This style was a hard sell for editors as the novel was originally written in the first person.

“I was writing against that Western model of a single narrative arc and adopting more of the repetitions of traditional Arabic folklore,” explains Cypher. “So, I wasn't willing to change how the story was told.”

Then she had a middle-of-the-night revelation — what if she changed The Skin and Its Girl to the second person? After that, Cypher immediately found a publisher.

“I realized that [the second person] comes up a lot in queer literature,” says Cypher. “I think it’s a way of the narrator having the authority to tell their story for the first time, and there's a specific listener that they trust, and yes, it positions the reader outside of that communication, but there's a charge around it, of overhearing a conversation or opening someone else's mail. There's that reflective space that I think matters.”

She wanted that “reflective space” for the characters in her novel.

“It’s not just about preserving the memories and family history in Palestine, and issues related to their immigration into the U.S., but also about what stories hold secrets — hold space for the truth — that a character like Nuha didn’t have the language to talk about, or didn't have an audience who wanted hear the truth,” says Cypher, “and I felt that really keenly when I was working on the draft.”