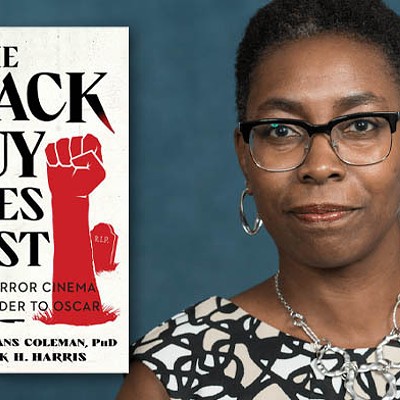

Get Out opens with a young black man lost in the suburbs, talking to himself. He’s bemused, describing the leafy streets as a “hedge maze,” but when a car slowly rolls up, panic sets in: “Don’t do anything stupid, just keep walking.”

Being black while in white spaces is the core fear of writer-director Jordan Peele’s horror thriller, an assured, smart and provocative debut. (Peele is half of the TV comedy team Key & Peele.) And that fear is on the mind of Chris (Daniel Kaluuya, from Black Mirror), who’s packing to spend the weekend with the parents of his newish white girlfriend, Rose (Allison Williams, Girls). Chris: “Do they know I’m black?” Rose: “No, should they?”

It’s a modern Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, where things get creepy in the country, even as Rose’s parents (Catherine Keener and Bradley Whitford) are enthusiastic huggers. Their isolated estate is big enough that there is live-in help, an African-American couple, both of whom seem … not quite right. And somehow Rose has forgotten that it’s the annual weekend when a slew of family friends come by.

You can watch Get Out as a basic slow-burn horror thriller, but the big rewards are in unpacking all that it subverts, as well as in processing its indictment of how things are not OK in “post-racial” America. The burden is on Chris to politely put up with the endless microaggressions (much is made of his physicality), and to make the social adjustments so he doesn’t upset anybody. Chris is unnerved enough to be thrilled when another black man shows up at the party, though the encounter only causes more alarm. In private, Rose is outraged on his behalf, which also falls to Chris to defuse: “Honestly, it’s alright,” he assures her.

Back in the city, Chris’ buddy, Rod (LilRel Howery), functions as an audience stand-in; Rod calls Chris out for sticking around, for trusting this odd family, and he unspools increasingly baroque conspiracy theories about what might be really going on. Rod is also the source of the film’s laugh-out-loud moments.

Peele knows the genre well, employing tropes like malfunctioning phones and locked basements. (Also, when a deer slams into your car on the way someplace, TURN AROUND.) Get Out follows the standard trajectory from weekend-at-isolated-house-that-starts-kinda-weird to the frantic final reel where the bodies pile up. (Another genre nod is that the eventual explanation is illogical enough to be silly, but the “what now” is more important than the “why.” Plus, it’s also a metaphor, if you want it.) But unlike most horror films, the black guy isn’t killed first, and the threat appears to come not from a deranged hillbilly but from an upper-class doctor who says cheerfully, “I would have voted for Obama for a third term.”

There is much to dissect in the back half of this film, but I won’t spoil what paths Get Out takes. Instead, let me advise you to get out — get out and see this sure-to-be-talked about film.