Wednesday, October 9, 2013

A Conversation With Ed Piskor

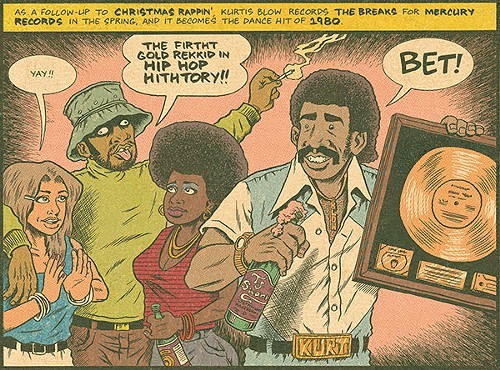

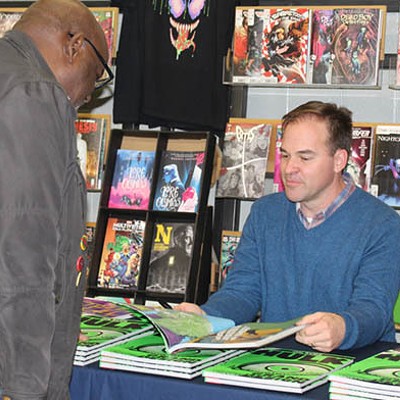

Some 40 years ago, hip hop was born of house and street parties in the South Bronx. Pittsburgh-based cartoonist Ed Piskor tells the story in The Hip Hop Family Tree, his new large-format 112-page comic from Fantagraphics Books. Piskor begins with DJ Kool Herc’s first break beats and continues through key figures like Grandmaster Flash, Kurtis Blow, Russell Simmons and Sugar Hill Records’ Sylvia Robinson. The sprawling, fast-paced book ends in 1981 — the year hip hop erupted into national consciousness. Four more volumes are planned.

Piskor is known for his critically acclaimed computer-hacker epic Wizzywig, and for collaborations with the late Harvey Pekar including The Beats, which Piskor partly illustrated. Hip Hop Family Tree — Piskor’s first book in full color — paints a big picture, from the music to the graffiti and more that comprise hip-hop culture. “It’s very important to note that the main character is hip hop, and all of these people are just little bits to create the whole,” says Piskor, 31, a life-long hip-hop fan.

Family Tree actually debuted as a weekly serial, starting Jan. 1, 2012, on web blog Boingboing.net. That exposure didn’t just garner the Munhall native a book contract; it has also gotten him featured on Time.com and earned admiring quotes from hip-hop icons like Biz Markie, who says, “This is the comic of all time.”

Piskor — lately in demand at events like the Brooklyn Book Festival — launches his book locally with an Oct. 10 appearance at the Hollywood Theater. (Piskor cautions that supplies of the book might still be limited at this event.) The event includes a screening of the landmark 1983 film Wild Style.

Hip hop’s always been with you?

I was one of the only white kids in my neighborhood. My house is in between several playgrounds. On [one] playground, there was a very prominent “Homestead” graffiti burner, and the “o” in Homestead was an eight-ball. Everybody will remember it who’s from around there. And I would just draw that endlessly. There are two hoops at the playground, so when guys are waiting around for next opportunity to play, they’re just in a circle, forming a rap cipher. It was just always there. It was like the air, you know?

Why the large format, a la the old comics “treasury editions”?

That was a very important format for the time that the story’s constructed [for titles including DC’s 1978 classic “Superman vs Muhammad Ali”]. I just wanted to give it that vibe of those old-time comics.

Why Fantagraphics?

I had offers from New York, big-time book publishers. I took a substantial pay cut to get this vision across. I chose based on format, in terms of what they would actually give me in terms of the book. And Fantagraphics, they never said no to anything. Because it’s a weird size. It’s a hard to shelve book for stores.

The benefit of going with Fantagraphics, too, is they’re very hands-off editorially. And these bigger companies were making suggestions that I should get from DJ Kool Herc to Tupac Shakur in like 250 pages. And that would be counterintuitive to everything that I’m building here. It would be a real MTV-ish [snaps his fingers], one-and-done. The beauty of the project should be that you can focus on as tight on these different subjects as the narrative compels.

Your color palette is also 1970s-era. You hand-draw and digitally sample colors?

I spend a significant amount of time on the computer to make it look like it’s not done on the computer.

For the book’s content, you credit sources including Dan Charnas’ book The Big Payback and interview archive thafoundation.com. What about visual references?

There was a great photographer during that period covering this stuff. his name’s joe conzo. He’s at all the events … he was there in the early days taking these photos. So he has this great archive of visual references that I can pull from. Just in terms of the new york city aesthetic, there’s a photographer named martha cooper who documented the New York scene in depth, and I use a lot of her material. [And] basically my favorite period of filmmaking is those gritty New York films of the ‘’’70s. I love Scorsese, I love French Connection, Pelham 1, 2, 3. wWhen I’m working, those flcks are going on in the background.

What did you do when your research sources conflicted?

Whether [a given incident is] an apocryphal thing that either happened or didn’t, what I’ll do is, I’ll build the sequence using [a character’s] word of mouth, so that I am personally not accountable for it being gospel. I put it in that character’s voice so that it’s them saying it, not me. ... I give three possible origins to how the term “hip hop” was coined. Because several people take credit for that.

So no readers have challenged you on any facts yet?

These old hip-hoppers [who like the strip] make me Teflon.

Is that creating new sources for the series?

My phone number is definitely in a network of rappers. I’m developing my sources. … It’s gonna enrich the content and just make it substantial.

What about hip-hop history should people know better?

The importance of the downtown New York City hipster art scene was crucial to the development and the propagation of hip hop. … It could have just been this very niche thing that just happened in the projects. But it was discovered by people like Debbie Harry, Malcolm McLaren. [Graffiti artist and future MTV host] Fab Five Freddy was like the bridge who introduced that Bronx uptown to the downtown art world. The bourgeoisie, they sort of nurtured it and allowed it to grow in the city, because they started bringing people like Afrika Bambaataa into these downtown clubs.

You think it really could have died out? Even before the downtown scene discovered it, hip had had already had hit records, like “Rapper’s Delight,” and Kurtis Blow had been on Soul Train.

It could have really been a fad. For instance, in the ’80s, there were several different kinds of musical genres that came and went. I’m thinking of go-go music in D.C., and I’m thinking house music in Chicago. Those things did not catch fire in the way hip hop did. Hip hop could have become just go-go music without the downtown scene, without the art world. And that’s where graffitit really plays in, because how do you sell hip hop in a gallery space with all these artsy people? You need the grafitti. That was very, very crucial in those early years.

How about pioneering performers?

One guy who I gained a lot of respect for is Kool Moe Dee. When I was a kid, all you would know is that crappy “wild wild west … wild wild west.” [But] his early records are my favorite rap records. He’s so amazing. … He was in a group called the Treacherous Three. And he originated speed rap — like shotgun rap. Then he got picked up by Jive Records. And they were like, “Listen, you could be more marketable if you slow down your pace and let kids be able to learn these lyrics.” So he really slowed his stuff to a snail’s pace. And it was diminished.

That’s the thing with these old reocrds, “Rapper’s Delight” and all these records that came out. … they’re like 15-minute records. What I love most about them is you really get the impression that the performers didn’t even expect this thing to last. So they put all their best stuff in that one record. It was like a Hail Mary pass. They’re like, “I may never get this opportunity ever again.” These records were created probably years after they’d already been performing. And not only performing, but performing in front of a hostile audience.

Imagine an audience that might have two extra dollars to spend. … So they’ll pay 50 cents to come to your party, and imagine if you’re wack .. and they dropped this money. They might punch you in the fuckin’ jaw. [The performers] have all this crowd-tested material, essentially that they revised and worked out for years and years and years, and they put that stuff on record, and it’s amazing. There’s such enthusiasm, there’s such pasion behind it. It’s like they put their 10,000 hours in before they made their first records.

Why do you spend four pages on the emcee battle between Kool Moe Dee and Busy Bee Starski?

It’s a battle between the old generation and the newer. And Busy Bee represents the old, and Kool Moe Dee represents the future, where things are going. Busy Bee is simply about getting the crowd in a frenzy. Saying stuff in a call and response fashion to excite people. And Kool Moe Dee’s stuff is content-based. That has won out. So it was very important to show this passing of the guard.

How much of a difference did it make rolling the material out for free on boingboing.net?

Boing boing has a huge built-in audience that’s to be respoected. They said there are four million unique readers per month, around the world. … That’ show these rappers [like Biz Markie] and stuff are discovering it. The reach of boingboing is making all that easier.

In the book, you note the similarities between comics culture and hip hop.

Historically, the idea that both of these things were created in New York City by essentially poor people, that’s like the backbone. Rap is people taking existing music to like create and do their own thing. In comics, it’s people taking the cheapest stuff you can buy, pencil and paper, to create narrative.

Pekar’s The Beats is also a cultural history. Did doing that book influence this one?

The structure that Harvey put together is what I used for this project. In most comics, the panel-to-panel transition is like a moment-to-moment thing. But in The Beats, years can travel between panels, and it’s like the art is in picking the moments that you choose to cover. Also, The Beats, it’s an ensemble cast, and how Harvey kinda juggled all of these components is something that I keep in mind while constructing this comic.

Do you keep up with hip hop?

I don’t know anything about modern rap, really. I feel like lawyers killed rap in the way that I know and love it [when DJs simply looped existing records]. Now it’s more lyrically based, and the production is kind of weak, to me, on almost everything.

You’ve already posted much of the material for volume two on boingboing. What time period does it cover?

It’s 1981 to ’83. As we move forward [in the five volumes], and more and more people are introduced, I can see [each] book being one year. By ’86, ’87, things are really rolling, there’s a lot happening, and I don’t’ want to skip over important stuff.

How far will the five volumes go?

Say I’m inspired to take it to the end of my interest [in hip-hop history]. I would take it to 1993 [and] Wu-Tang Clan. I’d end with the Wu.

ED PISKOR BOOK EVENT AND WILD STYLE SCREENING. 8 p.m. Thu., Oct. 10. Hollywood Theater, 1449 Potomac Ave., Dormont. $10. 412-563-0368 or www.thehollywooddormont.org

Tags: Ed Piskor , The Hip Hop Family Tree , Fantagraphics Books , hip hop , Kool Moe Dee , Program Notes , Image