Friday, September 12, 2014

An interview with former Pirates slugger Al Oliver; appearing at PNC Park this weekend

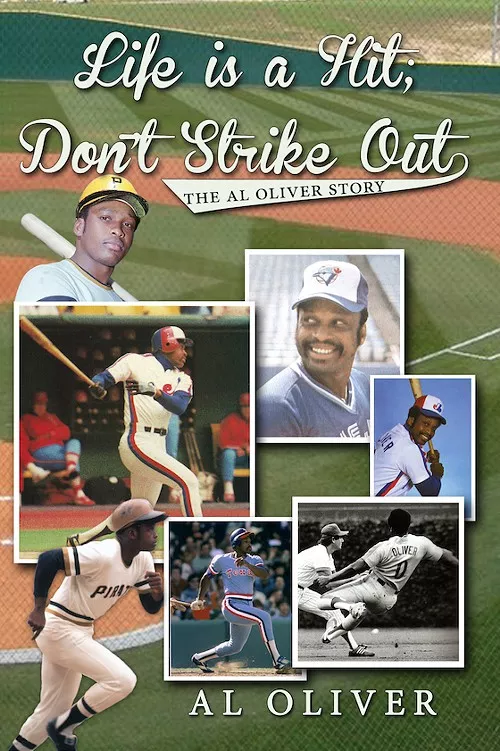

In advance of the September 30 release of his new autobiography, former Pirates slugger Al Oliver will sign copies of Life’s a Hit, Don’t Strike Out Saturday at the Majestic Clubhouse store in PNC Park from 1 p.m. to 2:30 PM and from 6 p.m. to 8:30 p.m.

Oliver joined the Pirates in 1968 before being traded in 1977 to the Texas Rangers. He’s a lifetime .303 hitter and collected more than 2,700 hits. The book examines his life in baseball and his struggles to be an everyday player despite hitting .300 in 13 of his 18 seasons, being named to seven all-star teams. It also deals with the racism he dealt with in the game, particularly early on in his career. Today Oliver is a motivational speaker and advocate for children, seniors and veterans.

Oliver talked to City Paper by phone Thursday prior to his return to Pittsburgh this weekend.

What made you decide to write an autobiography?

When Alfred [Adams of VIP Ink Publishing] first called — he saw me in an interview on one of the spiritual channels and he told me he thought I had a super career and that he thought my story might be bigger than my career. I thought about it for a week and decided it might not be a bad idea. People might know of someone but not know them. I’ve gone through a lot of things in my life and wanted people to know more about Al Oliver. My story shows that regardless of who you are and where you come from, you can make it. A lot of our young people today, for example, have a lot of talents but don’t use their gifts because they weren’t brought up in proper households to believe that they can make it. A lot of them get detoured off the highway and onto the service road, as I like to say. Detours happen to everyone, but you have to just gas that car back up and get back on the highway. Everyone detour.

You played in the Major Leagues at sort of a wild time. Players partied, some took illegal drugs but in your book you say you barely took a drink. How did you avoid the temptations that come with fame?

It was because of my foundation, my upbringing. If I was tempted to do something, I always asked, ‘What would my mother and father say if they found out? That’s what kept me away from it to the point that I was actually never tempted. My dad always told me you’ll be around people who will do foolish things and become fools but that doesn’t mean you have to become one too. I’ve always gotten along with everybody but I’ve also always been my own man. After the games some guys would go out and have dinner and some drinks but I was never big on that. A great night for me, especially on the road was to get a couple of hits and then go back to the hotel and get room service. I loved it, I still do. My teammates would call me the ‘king of room service.’ It was a special treat.

In your book you also talk about eating the same pre-game meal. Was it more about developing and keeping routines?

Dock Ellis [the former Pirates pitcher who had issues with substance abuse] always told me that he wished he had my discipline. I’m like that to this day. Dock used to always laugh at me because I was never out after midnight, but I wasn’t a drinker and that had a lot to do with it. I had my routines like my pregame meal. I would have two poached eggs, toast, sausage, hotcakes and coffee. I ate that meal before every game for 18 years. I was a creature of habit I guess.

You certainly had a different routine than Dock Ellis. The stories about Dock partying are legendary and he certainly had his issues with substance abuse. But you and he were best friends, you gave the eulogy at his funeral in 2008. How were you two able to be so close being so different?

There was a respect factor between me and Dock. In 1965 when I went to spring training he was the first member of the team that I had ever met. We were two 17-, 18-year-old guys and we just hit it off. I knew Dock had a great heart and was a great guy. I didn’t stay away from people just because they liked to drink as long as they remained in control and Dock was always in control. I think to his credit he respected the fact that I didn’t drink but could still be around it and not drink. As time went on our friendship grew and we became so tight because I knew Dock had my back and I had his. For example in 1975 they sent Dock to the bullpen because he wasn’t pitching well and he wasn’t happy. Some reporters asked me about it and I said I understood where Dock was coming from. I was always taught you stand behind your friends, you don’t throw them to the curb.

There’s a new documentary about Dock’s no-hitter that he says he threw while on LSD. Some people says there’s no way he was on the drug. You were his friend and you were that night, do you think Dock took LSD.

I was at first base that night so I was close to the action. I’ll say this, if a guy can throw a no-hitter on LSD, I believe he should be in the Hall of Fame. How did he even see the plate? I’ve never taken LSD, but I’m pretty sure there’s no way I could take it and hit a line drive. I’ve thought about that game a lot. Dock has always stuck to his guns with that story and I never asked him. If he says he did it, I believe him. Because if anybody could do it, it was Dock.

You had a reputation with the media and some of the fans about being cocky. What do you make of that label?

I don’t think the media understood where I was coming from. The things I said were harmless, especially by today’s standards. I said I wanted to play every day. Who didn’t? I wasn’t cocky, I didn’t even grow up in a place where that word was used. In my community, athletes were raised that way. If you had talent, your parents made you feel good about yourself and what you could do and accomplish. I think a lot of people missed the boat with their perception of me. I was an aggressive player but I was pretty laid back and if you asked me a question I would give you an honest answer, I assumed that’s what they wanted. But I think my honesty caught them off guard.

You talk a lot in the book about the racism you faced as a major leaguer. You received threats and had racial slurs thrown at you regularly, especially earlier in your career. You even talk about how you and your first wife received hate mail because people thought you were in an interracial marriage because of her light skin tone. How did that affect your career?

I have to admit, I was so positive as a person that when I heard that kind of name calling I would just look back at the person. There wasn’t and isn’t a racist bone in my body, I never had an issue with race. And I was proud of having that quality. But when they involved my wife and sent letters and hate mail, that was one of the hardest periods of my life. To think people would take the time to send letters to me and my wife just because they didn’t believe in mixed marriage, even though my wife was black … for me to say it didn’t bother me, I’d be lying.

In the book you talk about the end of your career coming too soon. Despite the fact that you were still hitting .300 or better in all but one of your last 10 seasons, your playing time dwindled and you describe it as sort of being phased out of the game. Do you feel like you could have played beyond 1985?

I think I could have played five or six more years, especially in the American League as a DH. I stopped getting regular playing time. I could still run and I could still hit because my conditioning was so good. I had won a batting title just a couple of years earlier at the age of 36. So I don’t feel like a I left baseball, I do feel like I was squeezed out. I could never understand how you could take a .300 hitter and platoon him. I could just never understand it.

A few years back there was a campaign to get you into the Hall of Fame through the veterans committee. Is that a dream you still have? How important is enshrinement to you at this point in your life?

You know, it doesn’t mean much at all to me anymore. I’ve given up on it and I don’t talk about it. The fans still do; the people who saw me play still do and that’s fine. I appreciate it, but it’s so far back in my mind now that it almost doesn’t surface. I wasn’t always seen as a team player by the media, but I like to think I was a pretty awesome team player who was always willing to play where they needed me and when they needed me. I didn’t complain. Dock always said it was amazing to him that I could be moved all over the place and still be productive. He also once told me that I should have gotten mad a couple times and knocked somebody out for the way I was treated. He said my career would have been shorter but I would have gotten the recognition.

Tags: Al Oliver , Pittsburgh Pirates , Pittsburgh , Hall of Fame , Image