Thursday, August 7, 2014

Experts say Pittsburgh triathletes exposed to unsafe levels of fecal bacteria

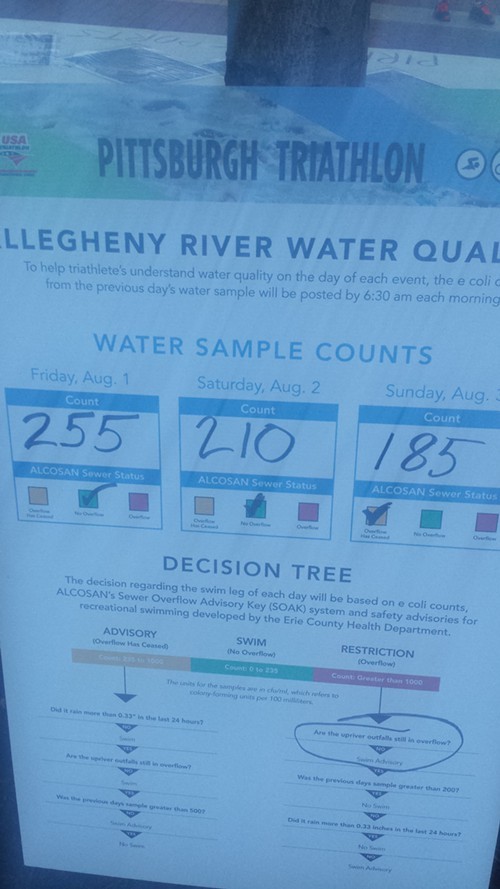

When around 200 triathletes started plunging into the Allegheny River at 6:45 a.m. Sunday, a chart posted by race organizers near the starting line suggested the water quality was improving.

But the chart's data was 24 hours out of date. And the state Department of Environmental Protection said today the actual level of bacteria in the water likely exceeded what it considers to be safe for swimming.

The chart was created by the event's host, Friends of the Riverfront, and was a response to athletes' complaints that they weren't adequately informed about water safety, especially since sewage backups have long plagued the event. On the morning of the race, the chart showed a downward trend in bacterial levels in the river, with 185 colonies per 100 mililiters on Sunday. But the lab cultures on which such numbers are based require 24 hours to grow, so the 185 figure actually referred to bacterial levels the previous day — before sewers likely backed up into the river following a rainstorm Saturday night.

Like many cities with aging infrastructure, Pittsburgh has a combined sewer system, meaning stormwater can overwhelm the system that carries raw sewage. When that happens, fecal-related bacteria can flow untreated directly into the river. According to the Allegheny County Sanitary Authority's overflow monitoring system, that's exactly what happened between 6:32 and 9:32 the night before the race. And indeed, when Friends of the Riverfront posted the Sunday numbers a day after the race, they showed bacteria levels one-third higher than those triathletes had seen on the chart.

- Photo courtesy of Sarah Quesen

- Bacteria counts posted near starting line

In small lettering at the top, the race-day chart did acknowledge that the chart displayed the previous day's readings, but some expressed concern the message wasn't clear.

"You think they just tested it that day. I think that’s what any normal logical person would assume," says Chris Mann, a 39-year-old Bloomfield resident who competed in the triathlon.

"The chart gave people a false sense of security," says Sarah Quesen, a leader of the Pittsburgh Triathlon Club's open swimming program, and a volunteer at Sunday's race. She says she has regularly complained about a lack of information about water safety. "It’s the lack of transparency that really gets to me."

"The poster was a naïve idea," acknowledges John Stephen, founder of Friends of the Riverfront. "I just decided to put that together in the past week, and in hindsight, I regret doing that."

Concern about sewer overflows prior to race time have been "a consistent issue with this particular event for a couple years," says Jim Wrubel, president of the Pittsburgh Triathlon Club. Wrubel says participation in the race has been falling — this Sunday's event had 208 finishers, down from 345 the previous year — and he ascribes the decrease to concerns about sewage in the water. Wrubel describes the chart used on Sunday as "misleading." If event organizers don't provide better water safety information, Wrubel says, he'll likely pull his organization's support of the event.

Race organizers say ALCOSAN's overflow advisories have been the main tool they've used to decide whether the river is safe for swimming. On 5:30 Sunday morning, Stephen says, he was told ALCOSAN was no longer leaking sewage into the river that the sewer system was no longer in overflow. "That was really the go/no-go decision when they determined the outflows weren't flowing into the river," he says.

But ALCOSAN's website warns that the river may "remain impaired for up to 48 hours after overflows have ceased." And John Poister, spokesman for the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, says that just because sewage isn't actively flowing into the river, water conditions could still be dangerous.

"You can take an [overflow warning] down the day after a rain event, but that doesn’t mean all the fecal matter is out of the river," Poister says. He adds that he's heard reports of illnesses connected to the Pittsburgh triathlon in the past.

The chart's presentation was muddled by another factor: It characterized the numbers as reflecting levels of E. coli bacteria, when they were apparently actually measurements of fecal coliform. The two are different measurements: Fecal coliform numbers include E. coli and other bacteria.

According to Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority spokesperson Melissa Rubin, event organizers asked the authority to test samples collected by a vendor, which collected water using a robot traveling along the swim route. But the authority didn't test for E. coli — instead it tested for fecal coliform. "There seems to be some sort of disconnect in the way Friends of the Riverfront presented the information to the public," she says.

She also notes that the authority isn't authorized by the state to provide official fecal coliform levels in the water. "The analysis was intended for race organizers — it was not intended for the public," she says.

There is some debate about whether E. coli is a more accurate measure of illness-causing bacteria. Either way, says UPMC infectious disease expert Amesh Adalja, "From a public health messaging standpoint, I think it should be very clear whether people are measuring fecal coliform or E. coli."

"These numbers have to be completely announced and interpretable by the general public," Adalja adds, "and if there’s any lag, that needs to be incorporated [into the announcement], especially if there was an ensuing rainstorm."

According to the DEP's Poister, the state's standard for "fecal coliform" concentrations in the water is 200 colonies per 100 milliliters — a number experts say was certainly exceeded on the day of the race.

According to data analyzed by the Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO), on the Tuesday before the race, fecal coliform levels in the Ohio River in Pittsburgh were 5,100 per 100 milliliters — nearly 26 times the state standard. Those readings were taken five days before the race, but Stacey Cochran, an ORSANCO environmental specialist, says levels "would have been exceeding [the standard]" even on race day — "by how much, I’m not sure."

On Monday, the day after the race, Friends of Riverfront posted new data for race day. It showed bacteria levels of 240 colonies per 100 mililiters.

Even so, "I don’t anticipate any life-threatening illnesses due to this kind of exposure," Adalja says.

If gastrointestinal symptoms present, most can be treated at home, he adds. And those worried about exposure should be fine if they experience a week without symptoms. (Some viruses, like Hepatitis A, can take six weeks to incubate, however.)

Still, some participants are finding it hard to shake the reality that they were swimming in, well, poop. "I don’t know if there’s enough chlorine in the world to get clean again," Mann says. "I’m really hoping I don’t get sick."

Editor's note (Aug. 8, 12:28 p.m.): This story has been revised to clarify the nature of sewage discharges into the river.

Tags: Friends of the Riverfront , Pittsburgh triathlon , Pittsburgh Triathlon Club , Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection , environment , contamination , feces , E. Coli , fecal coliform , Image