Friday, June 22, 2012

Cave Canem Poetry at City of Asylum

Terrance Hayes is a pretty good poet. Arguably, he's Pittsburgh's most prominent poet right now. In 2010, the National Book Foundation thought enough of him to hand him the National Book Award for poetry.

But the quality of Cave Canem's annual visit to City of Asylum last night was such that Hayes took the opening slot on a four-poet program and it didn't feel like a case of undue hometown deference to visiting artists.

In fact, departing the big standing-room-only tent City of Asylum had set up on a closed-off North Side street, I couldn't recall a night of poetry hereabouts in quite a while that was both stronger and more lively.

And I haven't even mentioned the surprise, evening-ending appearance by the venerable Nikki Giovanni.

Cave Canem was founded in 1996 by poets Cornelius Eady and Toi Derricotte to nurture African-American poets. Eady and Derricotte (who teaches at Pitt) have grown their baby into a major cultural force. They've got 344 national fellows. One faculty member is just-named U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Tretheway.

The reading, which drew some 300 people to Monterey Street, was part of the group's annual multi-day series of workshops and events in the Pittsburgh area.

The audience was filled with Cave Canem students and faculty, and the readers (all faculty themselves) felt free to do a mix of classic, new and even in-progress work.

Hayes led off with a stunning set of mostly new and unpublished poems, including one that in part describes his attempts to learn piano: "I was trying to play the 12-bar blues with two bars … I was tyring to play the sound of applause by trying to play the sounds of rain." He also read the provocative (and provocatively titled, after a parlor game) "Kill, Fuck or Marry" and a poem ostensibly about wigs whose wordplay was almost too dense to follow (and too rapidly spooled off to take notes on).

Acclaimed poet and novelist Angela Jackson followed. Her work, including an excerpt from a long piece about an enslaved forebear, was potently lyrical; a signature piece titled "The Smoke Queen," a breathless assertion of existentially indomitable blackness, brought the crowd to its feet. And her raunchily comic, folk-myth-imbued comic poem "The Man with the White Liver" had people all but rolling in the aisles, perhaps not least because Jackson at first seems so grandmotherly.

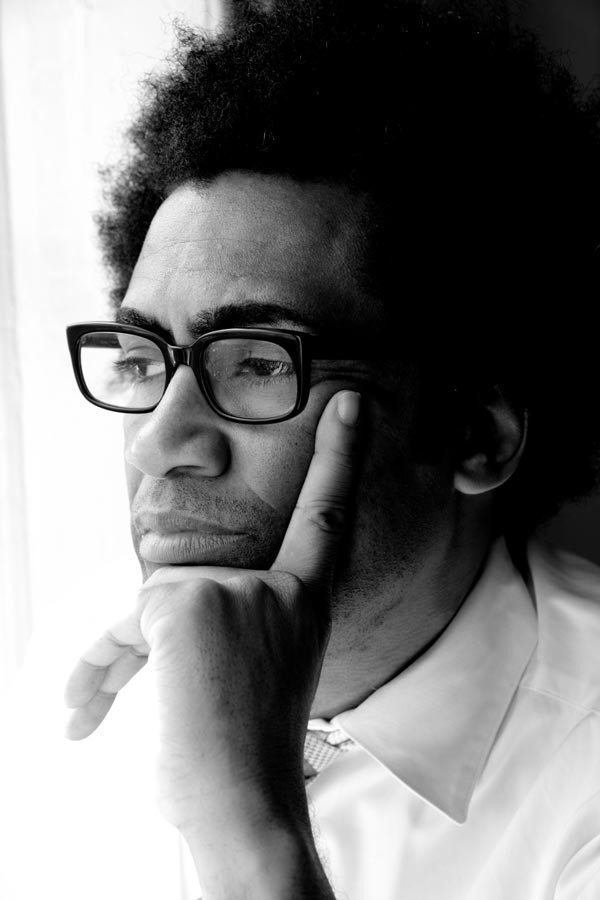

The young poet who introduced Thomas Sayers Ellis described him as "Albert Einstein and Richard Pryor." Though he didn't talk much astrophysics, the intensely cerebral but quite entertaining Ellis (pictured) lived up to the billing. When reading much of his work, he's got a unique, stylized manner, percussively emphasizing the rhythm. Ellis is experimental but also endlessly quotable. Some of his work's about being a black poet in a white-dominated culture: "I no longer write white writing, but white writing won't stop writing me." He read of women on the street who "clutch their purses because they want you to think you've stolen something," while in the art world, "they clutch their purses because they know you know they've stolen something."

One more: "Love is when people like the same food and like the same toys. War is when people dress up like salads and eat each other." He also performed ("read" is too tame) excerpts from a promising longer poem he wrote after Michael Jackson's death.

The offical program closed with another National Book Award-winner, Nikki Finney. She began with a calmly furious poem about the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina whose key images include a government helicopter making "observational" manuevers over a flooded city full of starving, dehydrated people but doing nothing to help them. She also read a wonderfully strange and affecting poem about her mother feeding her fish as an infant, and finished with a harrowing in-progress piece about a U.S. soldier who was raped and murdered on a base in Iraq.

Things wrapped up with Giovanni, a pioneer in the 1960s of the black-arts movement who now teaches at Virginia Tech. She read a couple pieces, including an hilarious brag with lines like "I am so hip, even my errors are correct."

Tags: Program Notes , Image