Wednesday, February 3, 2010

Contestational Cartographies

One of the first things I recall learning about the familiar Mercator projection map of the world is that it is wrong. This is the most common two-dimensional rendering of the globe, where the perceived need to reproduce its likeness rectilinearly, on a page, means that Greenland, for instance, ends up looking bigger than the continental U.S. (even though it's less than one-third the size).

I believe some alert junior-high social-studies teacher or other also hipped us to the insidious jingoism inherent in the fact that North America is placed at the center of most Mercators we were likely to see, implicitly validating our national narcisissm.

Such bias was a subtext of last week's Contestational Cartographies Symposium, at Carnegie Mellon. CMU's Miller Gallery and Studio for Creative Inquiry hosted a series of talks by artists and scholars who question the means we use to abstract our notions of the space we inhabit. (The symposium was linked to the gallery's Experimental Geographies exhibit, which closed Jan. 31.) One symposium contributor, the artist and 1992 CMU grad Lize Mogel, calls her practice "radical, critical, counter-cartography."

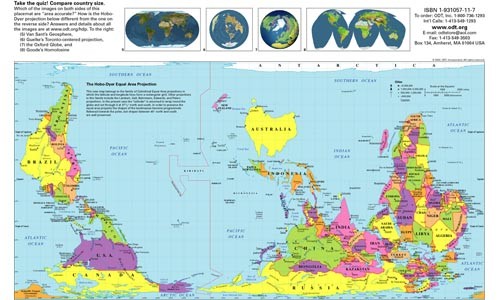

Mogel presented maps included the one depicted here. This version of the Hobo-Dyer Equal Area Projection is fruitfully disorienting, inverting the standard world map's "north goes up" orientation and addressing some of the sizing issues of land masses.

Mogel spoke Friday evening at the symposium. Many of Mogel's own maps, meanwhile, seek new ways to depict the effect of globalization. Among her other world maps was one that emphasized sites of the international shipping industry, from a relocated shipyard in Shanghai to decommissioned navy vessels in former shipbuilding capital San Francisco to the worksites in coastal Pakistan where workers do the dangerous job of disassembling the developed world's scrapped ships, largely by hand. In the map, the Panama Canal loomed huge.

Sizing, of course, that's not all that's wrong with maps. In his talk, artist and CMU instructor Pablo Garcia noted that the reason the earliest world maps deformed geography to fit a grid was for shipping purposes. In other words, the demands of the commercial elite have for centuries quite literally shaped the way we "view the world."

Perhaps even more fundamentally, maps "abstract" the world, providing a God's-eye-view of a planet that's complex -- culturally, ecologically -- and making it seem nearly as readily understood as a postage stamp. Mogel noted that while most Westerners regard maps fondly, a Nigerian artist she met said he "hates maps" because of what colonial mapping regimes did to his country.

Mapping, however, is a powerful genie that it's several centuries too late to stuff back in the bottle. Mogel and other symposium participants noted that popular access to satellite images and other technology puts map-making ability in hands beyond the governments and industries who traditionally controlled them. Perhaps that will help make our abstractions more honest and less harmful, as well as more diverse.

Tags: Program Notes , Image