It's less than one month before graduation, and Obama Academy student Donald Lewis can't wait to begin college at Robert Morris University in the fall.

It's been a great senior year for the 17-year-old and, overall, he's had a bright scholastic career. He was a member of both Obama's swim team and wrestling team for three years, and during the summer he works as a lifeguard. This past February, he was named the school's King of Mardi Gras. And right now, he's preparing to meet with representatives from the U.S. Department of Justice to lend his voice to the national My Brother's Keeper initiative, which serves to close the opportunity gap for young black men.

Lewis has come a long way from earning a 1.8 grade-point average in 10th grade (the year his father died) to earning a 3.7 this past semester. There's just one problem. Despite working hard to turn his academic career around, he recently found out he won't be receiving the Pittsburgh Promise, a $40,000 post-secondary scholarship for students in the Pittsburgh Public School District.

"I'm pretty upset because I was convinced that there was a good chance of me getting the Promise," Lewis says.

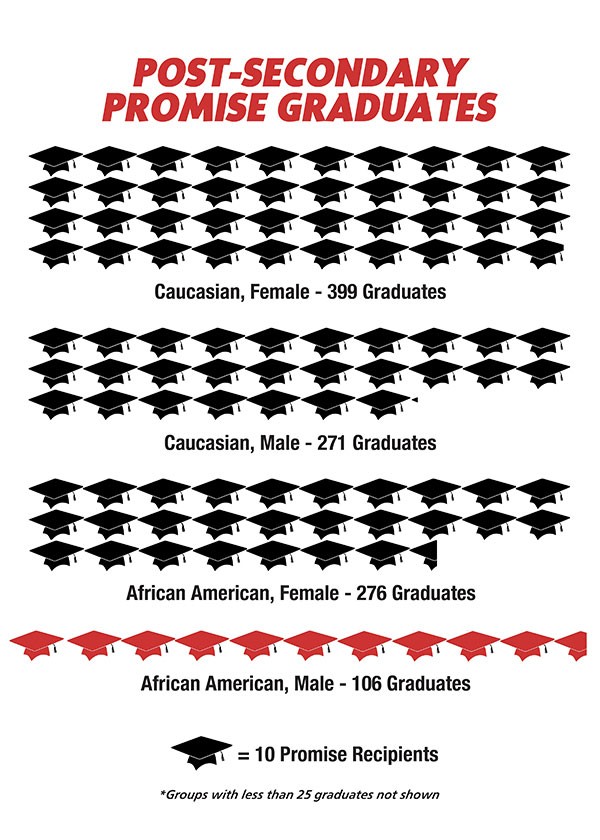

Unfortunately, his predicament has become the norm for black male students in the Pittsburgh Public Schools. Lewis and his peers are half as likely to receive a Promise scholarship as every other major student group in the district. To date, African-American males make up just 13 percent of Promise recipients, despite comprising 27 percent of the student population.

But this disparity isn't unique to the Pittsburgh Promise. Across the country, African-American males lag behind other groups in a number of academic indicators, like test scores and graduation rates.

Some say the effects of traumatic experiences and poverty have built barriers too high for black males to see beyond. Most experts agree that the inequity in Promise distribution is yet another way to measure how the district has failed this vulnerable population.

"We have a system of separate and unequal schools in Pittsburgh, that provide separate and unequal opportunities, and that naturally leads to separate and unequal outcomes," says Joseph Kennedy, head of the Fix the Promise campaign.

There are some programs making headway in reducing these opportunity gaps. For example, the district's We Promise program, which connects black males to mentors, has been a lifeboat for a number of students, including Lewis.

But activists argue that these programs don't go far enough, and that requirements for Promise eligibility maintain a system where the group perhaps most in need of financial aid, is least likely to attain it.

"If you're not getting the Promise, you're clearly not getting the same opportunities as someone who is getting the Promise," says Lewis. "There are a lot of lower-income families out there who can't afford to go to college and depend on the Promise. That means a lot more African Americans won't be in college, and that's a big issue, because if we can't afford to go to college, what are we going to do, just sit on the corner selling drugs?"

The Pittsburgh Promise was launched in 2008 as a partnership between the City of Pittsburgh, the city's school district and UPMC, which provided $100 million to seed the scholarship fund. It was originally meant to attract new residents to the city, but the Promise had more lofty goals as well.

"Creating access for kids to pursue higher education is clearly our priority," says Saleem Ghubril, executive director of the Pittsburgh Promise. "But it's not the only priority. It's also to use the scholarship as a way to lean on the district to promote school reform and measure that by college readiness."

Along these lines, the Promise has set a goal of having 80 percent of Pittsburgh Public Schools students obtain a post-secondary degree or certificate. In 2007, before the Promise started, 15 percent of students were meeting that goal. Nationally, the rate of college attainment for black males is 17.7 percent.

"It's crazy ambitious," says Ghubril. "There's a ton of work to be done, but I'm delighted that since the Promise was announced we've seen high school graduation rates grow, and the highest growth has been among African-American males. "

As of February 2015, 686 black males have received the core Promise scholarship. For white males, the number is nearly double, at 1,190 recipients. (The school district's current student body is 53 percent black and 34 percent white.)

To receive the Promise, students must have a 2.5 grade point average and a 90 percent attendance rate.

These requirements are the reason that Kennedy, a local education activist, started Fix the Promise, a campaign that calls for the elimination of Promise requirements. Kennedy, who has worked with students at Manchester PreK-8, in the North Side, and University Prep, in the Hill District, says that if students get accepted to a post-secondary institution, they should receive a Promise scholarship.

"Pittsburgh Public Schools has been locking in disparities by rewarding white students and ignoring black students," says Kennedy. "I am concerned that our students, black male students in particular, are being badgered about Promise readiness without getting the tools. When they have succeeded in leveling the playing field, we can talk."

Ghubril argues that the program's requirements are data-driven. Research and testimony from presidents at colleges and universities indicates that students who go into college with a 2.5 GPA and strong attendance do better in post-secondary institutions.

"If you throw somebody in the deep end and say, ‘Swim,' and they can't, is that really a fair thing to do to them?" says Ghubril. "The rule seems to be that high school-readiness is the best indicator for college readiness, and if that's the case, the answer isn't just to give someone a scholarship. It's to fix the systems when the systems are broken."

To help students who don't quite hit the mark at graduation, the Pittsburgh Promise created the Promise extension program. The program gives students with a GPA between 2.0 and 2.49 a scholarship to attend the Community College of Allegheny County for one year, and later transfer to another post-secondary institution if they maintain at least a 2.0. To date, 245 black males have received a Promise extension scholarship.

But this program isn't enough for Kennedy. He says black male students don't have time to wait for the education system to meet their needs.

Last year, in the 2014 graduating class, only 30 percent of African-American male students in the district were Promise-eligible. In comparison 73 percent of White males were eligible.

"I'm deeply concerned with the level of wishful thinking here because it undermines the needs and the wants of the students that are here now," Kennedy says. "I think these students deserve justice. Just because we have failed to educate doesn't mean they should miss out. This is an opportunity gap that [the school district has] created."

How to fix the education system is a million-dollar question, but one of Lewis' mentors, Michael Quigley, says administrators could start by looking at black males as "assets to be nurtured" instead of "problems to be fixed." Quigley is the outgoing program director of the Black Male Leadership Development Institute, a partnership between the Urban League of Greater Pittsburgh and Robert Morris University designed to increase educational and leadership opportunities for black males.

"These students are growing up in communities where there is violence and poverty, and then going to a school where their experiences are largely that they are problems to be solved," says Quigley. "So what else would you expect?"

Over the life of the Pittsburgh Promise, just 106 African-American males have used the scholarship and then graduated from post-secondary institutions. For white males, the number is 271, more than double.

"Anytime that a system consistently fails a particular population, that's not systemic failure, that's systemic success," says Quigley. "That system was designed to do just that, so it takes courageous leaders and courageous people to turn that system on its head."

Despite his involvement in programs like We Promise and BMLDI, Quigley is an advocate for broader reforms in the Pittsburgh Public School District.

"Often times we tinker around the edges and we focus in on a program here or there, and we lose sight of the core changes that need to take place," Quigley says. "The stakes are very high when black males fail in schools. The stakes are very high when they end up in the morgue or jail."

When the Promise was launched in the 2007-2008 school year, only 29 percent of black males were taking advantage of the program. Of the 445 black males who graduated from the district in 2008, 127 received the Promise. This disparity caught the attention of the Heinz Endowments, which supports the We Promise program.

"There are some real issues with access and opportunity, in particular for African-American male students," says Stanley Thompson, director of the Heinz Endowments' education program. "When you look at the number of kids who are taking advantage of the Pittsburgh Promise, you see that the numbers are significantly lower for black males. That to me is a red flag."

Thompson agrees that Promise disparities are a result of what's going on in Pittsburgh classrooms. But he says the problem is not unique to black males.

"If you find yourself in a high school classroom that is engaging, you find yourself studying something that is relevant, you're probably going to do fairly well," Thompson says. "The unfortunate thing is, we often times see high school students sitting in class and they're bored because teachers are not necessarily engaging them in the kind of active learning that could take place, so students disengage, and some might not come to school."

What is unique to black males is that many come from families living in poverty. Unlike their middle-class counterparts, Thompson says, these students don't have access to out-of-school "enrichment experiences."

"If you have kids that are not privy to those things, and we provide a type of education that's relegated to a classroom-like setting where we're never really asking kids to think about what's going on in their community, kids are not necessarily going to see school as being relevant," Thompson says.

This is especially a problem as it relates to the Promise's attendance requirement. In 2013, a district report found that 47 percent of high school students were chronically absent, meaning these students missed 10 percent or more of school.

"Research has proven, when kids feel like they are valued by adults in their learning settings, then what you have is kids responding in a way that shows they care about their own learning, and where they're going to wind up in their futures," says Thompson.

Nationally and locally, there are academics looking at how to more fully engage students in education. Among them is Daphna Oyserman, whose book Pathways to Success Through Identity-Based Motivation was the result of working with students in high-poverty schools in Detroit.

"Part of the problem with poverty is that your life is in chaos. My theory going in was, the more chaotic your life is, the more you can only think about right now," says Oyserman. "We looked to see what kids think about college. They assume their parents can't afford it. They know it's expensive."

For those living in poverty, and for a lot of inner-city black male students, Oyserman says, the idea of college is very abstract and out of reach.

"If the future seems far, you start too late," Oyserman says. "It's often easy for us to stigmatize the vulnerable, that they're somehow weaker. But if in your natural environment there's a lot of people who failed, but they never got back up, then that's your reality."

In Detroit, she worked with students over the course of 10 half-hour sessions in the first two weeks of 8th grade, which has been identified as a critical point in academic development. Oyserman had students envision the future they wanted, and helped them understand the many steps they would need to take to get there.

"Boys are the vulnerable group; they're not doing well," says Oyserman. "But this worked equally for all. Everyone had the same size of effect."

Pittsburgh Public Schools' We Promise program, which focused on African-American male students with a 2.0 to 2.49 GPA, is attempting similar methods locally. The program connects students with successful African-American male mentors from the Pittsburgh community who offer them help academically, while also exposing them to experiences and opportunities that success in post-secondary education will afford them.

"For the most part, our young men are in school, but they're a shell," says Jason Rivers, We Promise program director. "They've bought into the lie that education and college is not for them. We're unpacking years of bad practices."

The program has served 517 students since 2013. It originally worked with only 11th- and 12th-graders, but this year it was expanded to grades 9-12. Out of 393 We Promise students in 10th-12th grades, 191 — 59 percent — have had GPA increases over the past year.

While the program is showing results, it hasn't led to every We Promise participant receiving the Promise. Like Lewis, there are several students in the program who have fallen short of the scholarship's requirements.

Of the 126 seniors in last year's We Promise cohort, 24 received the core Promise scholarship and 53 received the Promise extension.

Data was not yet available for the 2015 graduating class, but as of press time, Lewis says he will not be among the Promise recipients.

Despite his disappointment, Lewis remains upbeat. But he was not always the smiling, successful, scholar his mentors describe today. He says he owes his change in attitude and outlook to the We Promise program. When Lewis entered 9th grade, he was like a lot of his peers — unaware of how his actions would impact his future.

"Of course people always say school is important," says Lewis. "But because it was 9th grade, I didn't think school mattered at that point. So it really was a hard hit on my GPA."

The following year, things deteriorated even further for Lewis after his father passed away.

"With the loss of my father I had to take on the responsibilities of being the man of the house because I'm the only boy, plus just the emotional stress it put on me, plus just watching my mom go through all of that. It was very difficult," Lewis says. "It just made me not want to do anything at all."

But Lewis says his mentors in the We Promise program wouldn't let him hold on to that mindset. Through his two years in the program, he says, they helped him change socially as much as academically, while steering him away from potentially dangerous distractions in Homewood, where he lives.

"It's difficult living in that area sometimes. I have quite a lot of friends who have gotten into trouble," says Lewis. "My mom and my dad have always been a good influence on me. But once I lost my dad, I sort of had the attitude of, ‘Oh I don't care anymore.' So if I hadn't met some of the mentors in the We Promise program, there's a good chance I might have given into peer pressure.

"I have a lot of friends that are going nowhere with their life, and I couldn't let that distract me anymore."

Receiving the Promise would have signified how much he's overcome. Because his school, Obama Academy has an international baccalaureate program, his courses are more challenging and weighted differently than courses at other schools. Lewis has a weighted GPA of above the 2.5 required to receive the Promise. But his unweighted GPA, the form of data the scholarship recognizes, is 2.4.

"Getting the Pittsburgh Promise would've meant like, ‘Yes, I did it,'" Lewis says. "Once I got in the We Promise Program, I began to strive for better grades. I got a 3.7 and I was like, ‘Yes, I'm definitely going to get the Promise,' and then it was like, ‘No, your average is still too low,' which made me feel like, ‘Why even try?'"

Lewis has filed an appeal, but says losing the scholarship won't keep him from attending Robert Morris to study psychology in the fall.

"It would just open so many more doors, because your college would pretty much be paid for, so you don't have to get a job while you're in college, so you can perform better," Lewis says. "But the We Promise program still improved my performance and my study habits, so I still know I'm going to do great."

Editor's Note: Support for this story was provided by The Equity Reporting Project: Restoring the Promise of Education, which was developed by Renaissance Journalism with funding from the Ford Foundation. Rebecca Nuttall was a 2014 recipient of the Renaissance Journalism Fellowship.

Editors Note: The original version of this story did not include numbers on what percentage of black male graduates in 2007-2008 received the Promise.