Facing at least a $4 billion deficit, Gov. Tom Corbett projected $810 million in cuts for K-12 schools, $625 million in cuts for higher education and the elimination of 1,500 jobs, among other cost-saving measures, in his 2011-2012 state budget proposal last month. Corbett called it a "day of reckoning" for many in Pennsylvania.

If Corbett's budget passes in June, however, it appears as though a day of reckoning will not come for the state's Department of Corrections. In addition to funding increases for the Board of Probation and Parole, from $142.1 million to $149.1 million, Corbett's budget also includes a $186.5 million increase in DOC spending, from $1.7 billion to $1.9 billion.

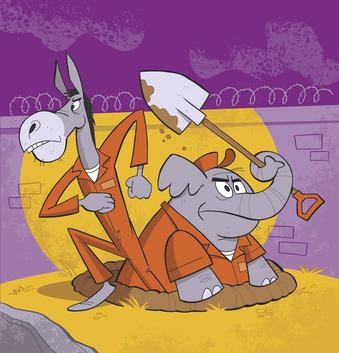

But that may not continue for long. After decades of increased bipartisan prison spending, there is a now bipartisan sense that it needs to be reduced. This push to trim the state's corrections budget may not go into effect for this year's budget, but it's gaining traction. And much of that traction is coming from former prosecutors at the state and local level.

The task will not be a small one. This year's corrections budget increase is built to support an overcrowded and expanding system. DOC reported at the end of March that 51,200 inmates were incarcerated in 26 state prisons built to hold thousands fewer. That March number represents a 500 percent population increase since 1980.

Even Corbett admits that trend needs to change.

"We need to think smarter about how and when and how long to jail people," Corbett said during his March 8 budget address. "We need to be tough on crime, but we also need to consider the fiscal implications of our prison system."

Corbett, who served as an assistant district attorney in Allegheny County before serving twice as the state's attorney general, is not the only person voicing concern about a state budget that extracts money from schools to support prisons.

State Sen. Stewart Greenleaf, a Republican former prosecutor who now represents Montgomery County in the state senate, is spearheading the Criminal Justice Reform Act (House Bill 100). Introduced in January with hearing dates to be determined, the act is supported by four Republicans and four Democrats, including Jim Ferlo (D-Highland Park) and Jane M. Earll (R-Erie) in Western Pennsylvania. HB 100 supports early release for inmates serving short sentences, educational support for inmates on their way out of prison, and alternative sentencing for drug offenses and other nonviolent crimes.

"The best justice system is one that has the development of a punishment but also has the development of rehabilitation," Greenleaf says. "And without rehabilitation it's a failure. Actually, it's worse than that. It's ineffective. It makes our streets more dangerous."

A main point, Greenleaf says, is that more than 90 percent of convicted criminals are eventually released back into their neighborhoods. So a centerpiece of any prison reform should be post-incarceration treatment and support.

Furthermore, Greenleaf points out that while the prison population expanded by 500 percent since 1980, the violent crime rate also went up during that time.

But the problem is not just structural. It's also financial.

"We're wasting money," he says. "We're building new prisons at $200 million a piece, plus there's 2,000 inmates per prison at $35,000 per person, per year, and it costs $50 million per year to run those places. I mean, there's your budget increase. And we're going to do that for, what, the next 30 years?"

Greenleaf's measure would not initially save money.

A memo sent to legislators on Dec. 22, 2010, calls for $50 million in additional corrections investment this year because "We must spend some money now to avoid ... huge additional costs in the future."

But Greenleaf says his bill would save costs. He explains that there are 4,000 inmates who would be affected by one proposal in his bill, for example, that would redirect inmates sentenced to short minimum sentences into local rehabilitation programs rather than state prison.

By Greenleaf's calculations -- which were aided, he says, by former DOC Secretary Jeffery A. Beard, who suggested the proposal -- the DOC could save $60 million if just that portion of his bill were passed. This is not a plan for the distant future, Greenleaf says; his proposals could influence the state budget this year.

"We could eliminate many cuts in education and elsewhere if we enact this bill," he says. "It's a cost savings and it'll keep our streets safer."

Democratic Auditor General Jack Wagner agrees.

"If you do not reduce your costs in corrections, you cannot have a healthy state budget," Wagner says. "Virtually every major state in the country has reduced their cost of incarceration and their number of inmates. That includes very conservative states such as Texas, New York and California."

Pennsylvania, however, had the largest prison-population increase of any state in the country in 2009. And, according to a report released by Wagner's office in January, Pennsylvania's corrections-spending increase in last year's state budget was higher than every state's but Wyoming and West Virginia.

"This is something that needs to be corrected now," Wagner says.

Which is a statement you'd expect from a Democrat. But Greenleaf and other Republicans are sharing the same sentiment.

Doug Reichley, the Republican vice chair of the House appropriations committee, is, like Greenleaf, a former prosecutor. He says his primary concern with the corrections system is recidivism -- inmates cycling in and out of prisons over multiple years.

Reichley references a portion of the prisoner population with mental-health and/or substance-abuse issues who don't get treatment inside the system. These inmates "don't have a very good chance of leading a law-abiding life," he says, which creates "a turnstile situation" where ex-prisoners often re-offend.

"That's not a very cost-effective way of dealing with people," Reichley says.

Reichley acknowledges that budget constraints -- and not civil-rights or humanitarian initiatives -- are driving much of the discussion about the corrections budget within the state's Republican Party.

"The parameters that we have before us ... really force us to look at the core services we are required to provide," he says. "I think most people would agree that incarceration facilities for people who have committed heinous offenses are essential services.

"But then we need to look within those numbers to see if there are efficiencies that we can provide or develop that allow us to reduce the overall cost while still maintaining the safety level we require."

Some say that's exactly what the state needs right now.

"It's as if we're being forced into sanity by a lack of money," says David Harris, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh who writes about criminal justice and national-security issues. He says the state has been defined for the past 30 years by a "mindless criminal-justice policy" that puts "tough-on-crime campaign slogans" ahead of rational sentencing guidelines.

"It's easy for a politician to propose tough criminal sentences, but we can't lock up every criminal in the system and throw away the key," he says. The result of that type of "easy solution," Harris says, is Pennsylvania's current budget situation.

"For any kind of real solution to increased prison spending and population numbers," he says, "you almost need people on the conservative side to come forward."

State Rep. Chelsa Wagner (D-Brookline) agrees.

"You can never waste a good crisis," says Chelsa Wagner, who is Jack Wagner's niece. She echoes others who say corrections reform will likely enter political discussion because of economic concerns. She supports Greenleaf's Criminal Justice Reform Act, she says, but is unclear how it will affect inmates re-entering society post-incarceration.

"Folks who have left the prison system have come to my office and said that they haven't received treatment while they were incarcerated," she says. "But more than anything, they tell me they need jobs when they get out."

Chelsa Wagner is referring to a "ban the box" movement that is taking root in Pittsburgh. This movement seeks to eliminate the check-box on the city's job applications where ex-cons are now required to disclose that they've been incarcerated.

"I don't necessarily think someone's prior conviction record is something an employer needs to know along with someone's name and their qualifications," she says.

City Councilor Ricky Burgess is leading the "ban the box" charge locally. Burgess did not return calls for comment, but Mark S. Lewis, president and CEO of the POISE Foundation -- which Burgess uses to distribute his Community Development Block Grant funds -- also supports the movement.

Once inmates are released from prison, Lewis says, the stigma of being an ex-felon often keeps an individual out of the job market, forcing him to make ends meet illegally.

"We tend to judge people based on their mistakes rather than how they can help society," he says. "By doing that, we end up rotating people in and out of prison."

Hide Yamatani, an associate dean for research at the University of Pittsburgh's School of Social Work, agrees.

"If more than four out of 10 adult American offenders still return to prison within three years of their release, the system designed to deter them from continued criminal behavior clearly is falling short," writes Yamatani in an email to City Paper. "That is a miserable reality, not just for offenders, but for the public safety."

Sen. Greenleaf's Criminal Justice Reform Act advocates for early-release programs, more lenient parole guidelines for nonviolent offenders, and treatment courts. Yamatani supports these measures, but agrees with Greenleaf only to a point.

"[The] future will definitely shift toward expanded utilization of the community corrections facilities," he writes. "However ... such unaddressed social conditions as education, economic opportunity, housing, poverty, and racial discrimination will continue to afflict public safety. Thus, the Criminal Justice Reform Act will reduce corrections spending in a valid way, but our government needs to do a lot more investment in the right area to 'make our streets safer.'"