In the city's most dangerous neighborhoods, sometimes the littlest things can lead to the biggest problems: a bump of a grocery cart in the store, a toe stepped on, a few bucks owed. That can be all it takes for a gun to be pulled and a body to drop.

"Doe" says he doesn't fear it. His friends started dying when he was in the sixth grade at Rankin Elementary. Now 20, he starts to mumble through a list of nicknames, trying to count them all before trailing off and giving up. "It's a lot of people," he says.

"At least 20," says his friend, known to those at the Rankin Christian Center as "Baby Hulk." He and Doe grew up together. They're tight.

"If something happened to him, that would hurt me, for real," Doe says. "I would probably revenge him. He's like my brother."

Baby Hulk ducks his head and sounds a little surprised. "That's love," he says.

Would he do the same? "Yeah," he says.

But for the mothers who lose their sons to such violence, similarly heard justifications for their deaths bring no solace.

"I wanted more for my child," Shawntika Rice says, sitting on the couch looking at pictures of her son, Rashee Coleman, in her mother's Hill District apartment.

The 17-year-old was shot in the back of the head in April 2011, hours after he returned home from spending a year at a group home for troubled kids.

"He came home for the Easter holiday," she says. She had dropped him off at the barber shop and was making spaghetti — his favorite meal — when she got the call that he had been shot.

Whatever the reason for the murder was — a dispute over money or anger over something stolen — it wasn't worth his life, she says.

It "doesn't justify why I had to bury my only child," she says.

Coleman's murder is still under investigation. Pittsburgh Police Bureau detective. Tim Rush declined to discuss the status of the case. Rice says police have followed up on information she's shared, but "keep hitting dead ends."

"I know people out there know who did it," Rice says. "His murderer is walking around these streets."

The long wait for closure has motivated her to join other mourning mothers who are trying to change a deeply held culture of silence in communities bearing the brunt of the city's violent crimes.

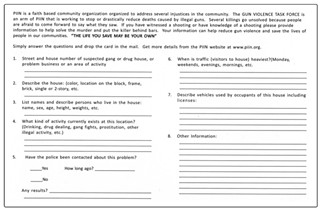

For the past five months, Rice has been canvassing, leading an effort by the Pennsylvania Interfaith Impact Network to curb shootings by asking people to write down on "hot spot cards" crimes or suspicious activities they've witnessed. She hopes she can act as a trusted middleman, promising anonymity and passing the information on to the police.

It's not an easy cause. In many cases, involving some of the worst crimes in the city's roughest neighborhoods, witnesses won't step up because of the fear that they or their family members will be harmed.

"Generally speaking, in almost every crime of violence, the perpetrator is known within the first couple of hours," says District Attorney Steve Zappala. "The question then is whether we have a prosecutable case."

Often, he says, that depends on whether first-hand witnesses are willing to testify.

Allegheny County marked 94 homicides as of mid-December. Of the 44 that occurred in the city of Pittsburgh, 25 were still under investigation, including the deaths of three people sitting in the stands of an October peewee football game at the Pittsburgh Obama International Studies Academy, in East Liberty.

"A lot of people saw what happened," Zappala says. "We have not been able to prosecute."

At the Rankin Christian Center, assistant program director Calvin Murphy works with the young boys and men most at risk of becoming either shooters or victims. They are those growing up without fathers, bouncing from house to house, coming into contact daily with drug traffic and drug use.

"Everybody has something to prove," he says.

Murphy says the shooters he's known displayed no signs of nervousness or remorse after the fact.

"When they're doing it and going around with it, they carry it like it never happened," he says. "There is no hint of anything until the day he is picked up. He's numb to it."

Indeed, the way to survive, Baby Hulk and Doe say, is to stand your ground and keep to your own business. You look to those you've grown up with, your "pack," to help protect you.

"Your feelings, you've got to keep them in your back pocket, keep them in your chest. You have to be more with your brain," Baby Hulk says. "You're thinking about yourself. You've got to think about yourself. It's a jungle."

And that means not helping the police — even when mothers like Rice are begging for them to come forward.

"My heart would go out to the mother," Doe says. "But if I snitch for her, that's putting my life and my family in danger. You can't worry about everyone else."

Baby Hulk agrees.

"You truly start to believe that," he says. "You start drowning stuff out."

Valerie Dixon has heard it before.

The mother of a Westinghouse High School graduate who was shot and killed 11 years ago at the age of 22, she founded the nonprofit Prevent Another Crime Today, or PACT, which produces billboards encouraging people to break the "code of the streets" and help solve Allegheny County's homicide cases.

Dixon, who also works as a court-appointed advocate for families of homicide victims, says that fear of the consequences of snitching "has been so deeply embedded that the attempt to come forward doesn't even occur."

But her effort with PACT has put her son's murderer as well as others in jail. Over the past 10 years, the billboards, which offer $5,000 rewards for information leading to convictions, have contributed to tips leading to 33 arrests, 27 trials and 22 convictions, she says. About $43,000 has been awarded to those who have called in with information.

But more than the money, she credits the impact she has had to the conversations she sparks — even though they may not produce a useful tip right away or convince someone to immediately come forward.

"They have to man up, when they're in that group, when everyone is looking at them. ‘We ain't no snitch,'" she says. "But when they go home, they think about it. Some of them do."

Richard Garland, coordinator of the Violence Prevention Project at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, also says that the bravado can be overcome.

"I don't care what you say about this generation. At the end of the day, they don't really want to kill anybody," he says. "They don't really want to do the shooting."

They're looking for someone — the right someone — to intervene and help them, he says.

"The guys who are doing what I call the hand-to-hand combat, they're not making any money. There's too much competition," Garland says. "Being a drug dealer is harder than construction work. You have the police who are trying to get you, you have your own friends, your own homies who are trying to rob you. You can't trust nobody. "

Garland says if anyone is going to break through the street rules governing "snitching," it is mothers like Rice and Dixon, those who choose to be a force for change.

"Moms make a difference on every level," Garland says. "When those guys go to jail, they don't call their so-called friends. Who's the first one they call? Mom. Who visits them while they're in jail every week? Not the girlfriend. Not the homies. Mom."

Shawntika Rice's effort with the hot-spot cards has yet to yield the kind of results she hopes for. Only a few cards have been returned since they were first distributed in August. But she remains optimistic.

"Just a little piece of information ... could lead to an arrest," she says. And "maybe one day, one of these cards will have information that leads to my son's murderers going to jail."