Here We Are

Twenty-five years after The Cynics' first performance, frontman Michael Kastelic sits in a booth at Gooski's bar, near his Polish Hill home, and considers the band's legacy. He talks excitedly of young bands like Thee Vicars, The Frowning Clouds and Los Explosivos -- bands that are carrying the garage-rock revival into a new generation, and all over the world.

"These are kids that get it," Kastelic exclaims. "They're my children. I know everybody always says they have the best kids in the world. The Cynics have the best kids in the world."

"Proud parent" isn't the first description of the mop-topped singer that leaps to mind. Almost as much as for his wild-man stage persona, he's known for surviving decades of the rock 'n' roll lifestyle, with all that suggests. As Cynics guitarist Gregg Kostelich notes, Kastelic "is entertaining -- on and off the field."

"The stories of my eccentric proclivities -- a lot of them are hyperbolic, and some of them are apocryphal," Kastelic says. "I do not deny anything, because this is show business, and who am I to deny anyone's fantasy of what Michael K. is?"

That reluctance to clear the air means that when you ask a question about his past, he's likely to serenade you with a few stanzas of a Winnie the Pooh song. And when I suggest we talk about how he started off down this road so many years ago, Kastelic's eyes widen in disbelief.

"Holy moly!" he exclaims. "That story could go on for hours and hours!" (See our abridged timeline of it here.)

In part, he's maintaining his cloak of mystery, but the passage of time is also a touchy subject in the world of rock, widely seen as a young person's game.

"I'm not saying that America is ageist -- it's just more throwaway culture," Kastelic says. Much of The Cynics' career has played out overseas, though, in countries like Spain, France and England, where "there's not really a prejudice against older musicians," he says, "and they don't give up on you." In Spain, there's even a Cynics' tribute band, called The Kastelics.

The Cynics' sound has undergone a tweak or two over the years -- sometimes more folk-rock, sometimes more aggressive -- but the bedrock has remained the same. It's a gritty combination of punk, '60s garage and psychedelia, topped with Kastelic's lovelorn croon, by turns tender and primal. Kastelic describes the garage-revival as part of a larger tradition, a "caveman beat" that includes the likes of Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and Bo Diddley, as well as Alice Cooper and The Velvet Underground.

Currently, The Cynics feature drummer Damien Llanes and bassist Angel Kaplan -- who live in Spain and Texas, respectively -- but other rhythm sections may fill in, depending on touring plans. The band's rotating membership over the years rivals Spinal Tap's.

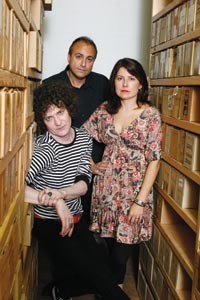

The core, though, has long consisted of an unlikely triumvirate -- Kastelic, Kostelich and his wife, Barbara Garcia-Bernardo. Each contributes qualities that set The Cynics apart from other long-running Pittsburgh rock bands: a ferocious live show, an ever-growing business infrastructure and a global reach.

Kostelich is "the epitome of a Pittsburgh entrepreneur. I'm the epitome of the Pittsburgh entertainer-clown," Kastelic says. "The way Barbara puts it now is that Gregg and I are more like an old husband and wife than she and he are!"

Though they've had brushes with fame, and those around them have blown up -- Green Day once opened for the Cynics, says Kastelic, and Fugazi debuted by opening for them -- the band is neither rich nor rock-star famous. But it does get a steady stream of requests to play. "We only go to places if you really, really want us. It's a great position to be in," says Kastelic.

It sure sounds a lot better than becoming a stay-at-home act that trots out a couple of times a year to play a nostalgia show for local mainstream audiences. At least when Kastelic talks about playing rib fests with REO Speedwagon and Blue Öyster Cult ... he's just pulling your leg.

"You know, we're hams -- why would be playing music this long if we weren't hams?" he says. "Holy moly!"

Get My Way

Walking through Get Hip's North Side warehouse with Gregg Kostelich is like navigating a rock 'n' roll Bat Cave. There are disorienting turns and chambers packed with the stuff of daydreams run wild -- provided the daydreams in question are those of record geeks and musicians.

In the main offices, Cynics posters adorn the walls and guitars are stacked 10 deep; cavernous shipping and overstock areas are crammed with new vinyl and CDs, and used collections purchased to resell online. A fireproof room houses Kostelich's personal vinyl collection, "stuff I've really enjoyed from 2- or 3-years-old to now" -- or at least 6,000 of them he doesn't keep at home. A second fireproof room contains The Cynics' master tapes.

When other tenants vacate space in the building, Kostelich finds something to fill it, expanding the Get Hip empire. (Get Hip's latest venture -- screening its own T-shirts -- is housed in a small room and bathroom.) Get Hip's mission is similarly sprawling, according to Kostelich. "It's not just the label," he says, "it's distro, and turning people on to good music."

Kostelich started the record label to release The Cynics' music, "by default," because he couldn't find another label to do the job. Similarly, Get Hip became a distributor for itself and other labels when Kostelich couldn't find a suitable one. He's expanded into other areas too -- sometimes for business reasons, and sometimes for what seems a byproduct of a record collector's obsessive compulsion.

For example, Get Hip inspects, packages and shrink-wraps its new vinyl by hand. Trusting manufacturers to do this means being charged for damaged or defective discs, Kostelich says. And before used records are priced and sold on eBay, they're cross-checked against Kostelich's personal vinyl collection, to fill in any gaps.

Kostelich describes himself as "hardheaded" -- while Kastelic suggests "megalomaniac" -- and sometimes thinks he's made more work for himself than he'll ever be able to complete.

"It's very depressing," he murmurs wryly, surveying all the past and future projects around him. "You think you're going to live forever.

"I feel like I'm a bean-counter over pennies, not just for The Cynics but for everybody who's on the label, and then responsible for all the vendors," he adds. "I never looked at it as a big drag when things were going well, but I have now realized how much has been a ball-and-chain through my life, 20 years."

And despite all the business trappings, Kostelich remains a rock 'n' roller at heart, still exhibiting the fervor and sneer that started him down this road so many years before. Listening to Jimi Hendrix that morning on the way to the office, for example, got him fired up to wail on the guitar himself. "I still have the crazy, silly kid shit. The kid's still in me," he says.

Kostelich characterizes the Pittsburgh scene in the early '80s with his usual, well, cynicism. "Nothing was going on! Like now," he says, only half-joking. Influenced by his older brother and his druggie friends, Kostelich grew up "living the '60s," he says, and obsessed with the music. When the punk era rolled around, he thought, "If I can just put the punk attitude with the garage, that would be garage-punk. That's the kind of band I want to put together." And so he did.

The singer for the band's July 1984 debut at the Electric Banana was Mark Keresman; The Cynics we know today started with Kastelic's first gig in November 1985 -- and the tensions which define and sustain the band began at exactly the same time.

"We were loud, and [Kastelic] was so pissed off, he was gonna quit: 'I can't hear myself, fuck you!'" Kostelich recalls. "It was our first argument, which is great -- we've been arguing about it ever since!"

While the band initially thrived in the underground scene, The Cynics seemed an awkward fit for more mainstream Pittsburgh. "Imagine playing the jock bars, showing up looking like we're out of 1966. We got fucked," says Kostelich. "Now, it would be cool. We got shit for it, nobody was doing it," he says. "We were a fish out of water."

The ensuing ups and downs -- which include a five-year break-up during the latter half of the 1990s -- have been documented repeatedly in what Kastelic calls the "perennial article" [see "The Cynics: An abridged timeline"]. But not only are Kostelich and Kastelic still at it, but they're the only members who've managed to hold on.

"All I wanted to do was this, and Michael, I think, is similar," Kostelich says.

Turn Me Loose

When Michael Kastelic talks about the past, it seems part myth-making, part psychodrama. He plans to write his memoirs and already has a title picked out: Encore, Encore. (He says he wants the same phase to be his epitaph.) One senses he's been grooming this material for awhile. It's all part of his role as "entertainer-clown."

Kastelic's path toward "weird performer" began when he was a kid, after his grandpa, a policeman, gave him a bunch of '60s records that had been stolen from an AM radio station; the station had replaced them by the time the police recovered the music.

"Before that, I either wanted to be a DJ or a backhoe driver -- I was very infatuated with things that made big noises," Kastelic says. "But as soon as I heard those Eric Burdon records and those weird '60s records when I was 9, I kinda wrote off 'backhoe driver' and decided 'I kinda want to do something a little more like that -- they dress better.'"

In addition to loud noises and cool clothes, "one of the reasons I chose the business of show -- or maybe it chose me -- was that I wouldn't have to worry about people judging me," for being gay, Kastelic says. "I always thought in rock 'n' roll and especially punk rock, that musicians were expected to be libertines and at the very least, bisexual. It's part of the narcissistic disease to want to be loved by everybody!"

One of the many bands Kastelic played in before joining The Cynics was a proto-noise band called Dub Sex, short for "Dubious Sexuality" -- one of his early forays into Pittsburgh's burgeoning punk scene, where he refined his "onstage assault tactics."

"It wasn't even until later in high school when I found out that the Pittsburgh punk-rock scene was actually happening," he says. "The first time I saw The Cardboards, when I was like 14 years old, it was probably the scariest thing I'd seen in my life." It helped him realize there was music in his time that was connected to the raw '60s music he was into, not just the current radio rock he found pompous, like Led Zeppelin and Genesis.

Before joining The Cynics, he and Kostelich "were close, almost like brothers," Kastelic says. "We were both big fans of each other." The way he remembers it, he joined the band after The Cynics' first lineup played a show. "We were all doing acid at this party on McKee Place, and we were sitting on the steps. I said 'Gregg, that show was really good, but you guys would be so great if you had a real singer.' He said, 'Well, why don't you do it? Why the hell don't you do it, are you a coward?'"

In the years since forming that alliance, "my idiosyncrasies have definitely blossomed," Kastelic says. Even so, Kostelich says that no matter what condition his vocalist has been in, "Michael's always on time."

"I never went into it, even in the punk-rock days, saying, 'Oh, I just want to be unprofessional and sloppy about it,'" Kastelic says. "I always wanted to be the best at it -- even if it was the sloppiest, dirtiest punk rock." When Kastelic wants to praise other musicians, a frequent term of approval is "professional."

As for Kostelich, "I was going to say that he's mellowing with age, but I don't think that's at all it," Kastelic says. "I think he's becoming smarter with age, becoming more crafty." While the two have written most of their songs together, they still battle over things like which tunes to play at a gig.

"That happened at our first show, and it still happens," Kastelic says. "I don't know if that will ever change."

Another thing that hasn't changed is Kastelic's drive to push boundaries and buttons. "My onstage persona as well as the sound of our music are both fairly confrontational," he says. "Everybody dances, has fun, and we have happy songs, but it's definitely not safe -- it's loud and passionate and someone could really get hurt at a Cynics show.

"Although it's usually me getting the most bruised up."

Different Worlds

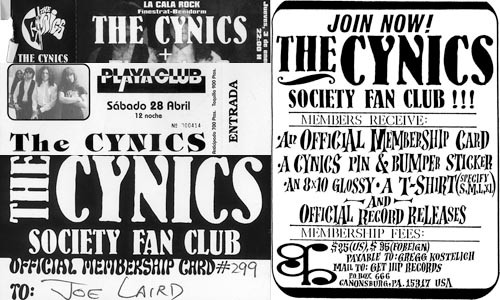

At Get Hip headquarters, Barbara Garcia-Bernardo, the label's vice president, has cherry-picked some Cynics memorabilia to look through: slick 8-by-10-inch promo photos; fan-club membership cards; fliers from gigs in Mexico; old stickers and buttons. There are issues of Bust and Playboy that featured the band -- as well as police and hospital documents from Kastelic's misadventures in Spain. Even if you don't speak Spanish, "traumatismo perineal, hematoma escrotal" tells all you need to know about the injury Kastelic sustained when an audience member pulled him offstage ... by one leg.

That these items still exist -- and can be located amid the flotsam of 25 years of rock 'n' roll -- gives you an inkling of Garcia-Bernardo's importance to Get Hip and The Cynics. Kastelic has described her as "our manager, publicist, booker, everything." She's also helped create the global agenda that has kept their fortunes independent of their popularity in Pittsburgh.

Garcia-Bernardo took the first steps toward that role in 1990 while living in Madrid, where she was very plugged in to the garage-rock scene. She helped out at a local record store and with concert promotion, and kept in touch with touring bands that came through town.

At that time, The Cynics were one of the better-known bands in the garage-revival scene, Garcia-Bernardo recalls. When their van broke down during their European tour for Rock 'n' Roll, record-store owner and promoter Pepe Ugena of Record Runner covered their airfare home and hotels in exchange for recording a live album for him in Madrid.

With The Cynics stranded in Madrid for several days, Garcia-Bernardo and Kostelich "became really good friends," she says. When The Cynics got home, "he sent me postcards, and we kept in touch," and invited her to visit in Pittsburgh.

"I really needed a change -- I was really burned out and I hated the job that I had," Garcia-Bernardo says. And at the same time, "I was getting more into the music, I was doing a lot of posters with shows, helping manage and promoting.

"When I told him I was coming, he was like, 'What!?'"

Kostelich was staying with his mom between tours at that time, and Garcia-Bernardo found early 1990s Pittsburgh "dreadful, dreadful" after Madrid. But, she says, "I just had this gut feeling -- 'Hey, I really like this!'"

Over the next two years, she shuttled back and forth between Pittsburgh and Spain and started helping Kostelich with various aspects of Get Hip and The Cynics. Eventually they married. She's called Pittsburgh and Get Hip home ever since.

"Somehow we keep doing the same thing and we keep liking it," she says. "As long as I get to travel."

In addition to work with the label, she frequently accompanies The Cynics on tour, where her organizational skills allow the band to relax and focus on playing. "Gregg and Michael say they don't want to go if I don't go!" she says.

Garcia-Bernardo says she's no more involved with Pittsburgh's scene than with any other city's. "A lot of people don't realize that we have a worldwide business. I can't really concentrate too much on any one market."

Even so, she and Kostelich are kicking around the idea of opening a retail location in Pittsburgh, and possibly expanding into yet another wing of their warehouse space, where they could host dance parties and record swaps. Recently, the two participated in a dance party at Remedy in Lawrenceville, spinning rare garage rock.

The Cynics, meanwhile, continue to tour internationally, with dates in the U.S. and Spain this month. "In a lot of markets, it's very, very consistent," Garcia-Bernardo says. "The band being consistent goes with the consistent good audiences, and I think that's the key."

It also means Pittsburgh shows by the band are few and far between, even though they're seemingly here to stay. "I've tried moving Gregg a couple of times," Garcia-Bernardo says, to no avail. "He has his roots here, but the biggest thing is the vast amount of stuff he collects. He's a major packrat and refuses to part with anything, and that would make moving a monstrous task."

Living Is the Best Revenge

Garcia-Bernardo's international contacts helped Get Hip and the band become increasingly global -- and not a day too soon, as local support for the band was drying up. (Kastelic estimates their local peak came in 1990.) "We had our scene at the Electric Banana, and when the Banana closed, we carried that scene to the [31st Street] Pub a little bit, and Graffiti, and Cloud Nine," Kostelich says. "And when Cloud Nine closed, that was the end of it."

Since then, Pittsburgh has become more homebase than hometown crowd. As Kostelich tells it, The Cynics won the world but lost Pittsburgh, once their original scene started to dry up. "That generation of people got married and had babies, so they're not coming out," he says.

Kastelic and Kostelich have mixed feelings about that. Though Kastelic has hopes of engaging the local student population at some point, he admits, "I'm just happy to be home and not have to go out and play!" In any case, he surmises, "People in Pittsburgh are more comfortable with something they know and aren't threatened by."

In fact, at their most recent album-release show, The Cynics drew about 80 people to the Rex Theatre on a Saturday night. "I was never so humiliated," Kostelich says. "I don't know what to fuckin' say about this town."

Even Cincinnati is a better market than Pittsburgh for The Cynics these days. At a recent show, "It was incredible, the turnout," Kostelich says. "There were a lot of MySpace young kids -- [Kastelic] corralled them," he says.

Chasing the band's audience is the right call, Kostelich believes: "I don't want to name names, but there's even head honchos that had their salad days, and they're stuck playing Pittsburgh." But if you want to see this Pittsburgh band in its element, you might have to travel some distance. Say, to Austin, Texas.

This spring, after several performances earlier in the week, The Cynics downed the last flat backwash of the South by Southwest music festival with a Sunday-night gig on the outskirts of town. The venue was an outdoor stage, with a miniature pavilion over a concrete pad and an adjacent weird little bar. The small crowd trickling in looked around mid-thirties to mid-forties, many dressed in Mod styles. Many festival attendees had already left town, and it didn't look too promising.

Then The Cynics started. It's cliché to say that everything changed, but that's exactly what happened. As the band launched into song after song, Kastelic gyrated to what he calls the "caveman beat," wielding maracas and tambourines, gesturing obscenely with the microphone, and controlling the ebb and flow of energy in the night air. Everyone was on their feet, dancing, sloshing plastic cups of beer, whistling at the band, knocking into each other, grinning absurdly. This is the kind of rock 'n' roll mess that The Cynics can still inspire after 25 years -- and on a school night, no less.

"Everybody was gone, yet it was a great crowd," Kostelich recalls. "All the musicians that hung around that were cool were fucking there, and we had a great set."

Unbeknownst to The Cynics that night, the audience included Sky Saxon, vocalist and bassist of '60s psychedelic garage-rockers The Seeds -- forefathers of the racket and the look The Cynics unleashed on Pittsburgh at their first gig, decades later. It was to be one of Saxon's last nights on the town: He died unexpectedly soon after. In true rock 'n' roll fashion, Saxon's real age is unknown: A New York Times obituary suggests he was 71, but notes that his widow wouldn't confirm it "because he believed age was irrelevant," she said.

The Cynics might agree. Kastelic says he sometimes thinks of The Cynics in terms of a recurrent dream about turtles -- his pets when he was a kid.

"I loved them because they were so peripatetic, just walking around all the time with their house on their back," he says. "I don't know whether we really won the race or won any prizes, but I think by going slow and steady, we have a better legacy."

"I can only hope that some time in my dotage, some TV show or movie will take one of our songs and use it, so I can maybe afford to get health insurance or something!" he adds. "I plan to live to be about 102 years old -- I plan to definitely outlive Sky Saxon."

The Cynics' October tour dates:

10/09 Newport, KY – Southgate House

10/10 Atlanta, GA – Star Bar

10/11 Atlanta, GA – Criminal Records in-store

10/28 Gijon, Spain – Savoy Club

10/29 Madrid, Spain – La Boite

10/30 Vitoria, Spain – Helldorado

10/31 Burgos, Spain – Estudio 27

11/1 Albox (Almeria), Spain – Rock Albox 25 Aniversario Festival