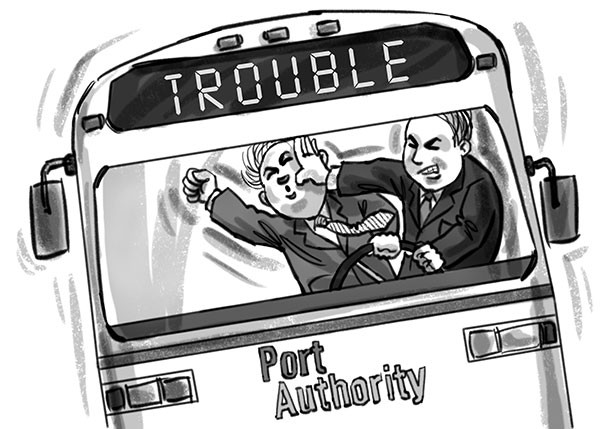

Port Authority riders are used to change: route adjustments, fare increases, service cuts. But in the weeks to come, the transit agency itself will have new leadership at the wheel ... and the road ahead may be bumpy.

Under a state law passed in July, the authority's board is set to be overhauled in September. And where Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald used to have total control of the appointment process, the new law compels him to share that power with Gov. Tom Corbett and legislative leaders in Harrisburg.

That could affect everything from scheduling routes to purchasing buses, from hiring executives and lobbyists to approving union contracts. Ultimately, the changes could even determine whether the agency continues to exist in its current form.

"The board makes all the major operating decisions," says Helen Gerhardt, a community organizer with Pittsburghers for Public Transit, an independent rider- and driver-advocacy group. "And they have such a key role in approving the labor contract, which is key to the whole function of the operation of the system."

Fitzgerald is putting the best face on the changes, noting that nearly 60 percent of the authority's operating funds come from the state.

"I think it's great they're going to be involved, learning about it, seeing what we do, helping make policy," says Fitzgerald.

Still, the changes are a dramatic turnabout for Fitzgerald, who just months ago asserted the right to remove any appointee at will. And given that Republicans — who control every branch of state government — have often been indifferent or even hostile to urban transit, some worry the new rules will add turmoil to an already difficult climate. The agency is currently without a CEO, and $30 million in additional state funding — part of a package Fitzgerald worked out to help avert a crippling 35 percent service cut — is also in jeopardy since the state legislature stalled on passing a transportation-funding package.

"I hope that this doesn't become a political football and nothing gets done," says current authority board member Amanda Green Hawkins. "We have so many people who rely on transit."

The restructuring is a result of Act 72, which Corbett signed on July 18. It expands the board from nine members to 11. The larger board will include one appointee each from the governor, and from the Democratic and Republican caucuses in both the state House and Senate. The county executive retains control over six picks, though two of those are to be recommended by at least one of a handful of civic groups interested in transportation. Those range from the Allegheny Conference business group to the Committee for Accessible Transportation, a disability-rights group.

Gerhardt, the transit advocate, is concerned about the lack of labor and rider groups among those advisory groups. And with a "substantial board majority representing suburban, corporate and rural interests," she's worried that board members lack connection to the concerns of urban riders.

"These people aren't directly accountable to the voters, so they don't have a constituent base or incentive to really represent the needs of riders," she says.

It's not clear whether Gerhardt's fears will come to pass. At press time, only Senate Democrats had made an appointment: state Sen. Jim Brewster (D-McKeesport), who also sits on the Senate transportation committee. (Fitzgerald says he's "still evaluating" his appointees.) But Act 72 also sets out new procedural rules that might complicate matters further.

Under the new law, a supermajority of seven members must agree to "take action on behalf of the authority."The upshot: For Fitzgerald to effect changes at the authority, he will need support from more than his own appointees.

And Republicans have a special power to thwart Fitzgerald's agenda. Tabling a bill — delaying action on it — ordinarily requires a majority, unless it's opposed by board members appointed by the party opposite that of the county executive. In that case, only two opposite-party votes are needed to halt actions like hiring a CEO or approving contracts over $5 million.

The tabling power turned off Sen. Wayne Fontana (D-Brookline) and Jim Ferlo (D-Lawrenceville), who along with Brewster voted against the bill. "I don't think there needs to be that much Harrisburg representation," says Ferlo, who calls the requirement "ridiculous."

"I've never seen any other board or authority in the state like this," Ferlo adds.

In Philadelphia, the board of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority (SEPTA) includes appointees from the governor and the legislative caucuses. But SEPTA is a regional system whose board includes appointees from the five counties it serves. If representatives of areas totaling at least one-third of the population object to a proposal, it takes three-quarters of the board to override the objection.

"There's a lot of converging interests here," says SEPTA assistant general manager of public and government affairs Fran Kelly. "They come from city versus county, Democrats and Republican." Still, he says, "Everyone gets a fair shake."

Fontana doesn't oppose giving the state more say at the Port Authority — he has previously proposed his own bill to do so — but says that allocating veto power over major decisions "goes too far when the questions become ‘Is that a guy a Republican? Is that guy a Democrat?'"

Fitzgerald acknowledges the provision could be "problematic if people wanted to get in there and ‘cause trouble.'" But he notes that tabling a motion can only "slow it down to slow it down," since a majority can later untable it. "There's kind of checks and balances on both sides."

The legislation also requires a study of other potential reforms. One where there is broad agreement instructs the state Department of Transportation to study consolidating the authority with other local transportation agencies. Fitzgerald campaigned on the idea of regionalization, which was also recommended by a Corbett task force.

The law also instructs PennDOT to study the "potential privatization of authority services" to reduce costs and increase revenues. PennDOT spokeswoman Jamie Legenos says that the department is doing preparatory work for those studies.

"Those are parts of the bill I wish weren't in there," says Senate Minority Leader Jay Costa (D-Forest Hills). "But Democrats weren't in control of the process. It was something important to the House Republican colleagues, and as a result that language stayed in there." (Republicans in the legislature did not return calls for comment.)

For Fitzgerald, Act 72 could have been much worse.

In the original version proposed by Senate Republican Leader Joe Scarnati, Fitzgerald got only one appointee. The others would have been made by Allegheny County Council, the mayor of Pittsburgh and elected officials from counties contiguous to Allegheny.

"Given the ever-increasing amount of funding the state contributes to the Port Authority it is appropriate for state officials to have a voice on the board," Scarnati wrote in a March 28 co-sponsorship memorandum. "It is also important that local influence on the board be attained from a diverse group of individuals."

The proposal set off a heated exchange. Fitzgerald slammed Scarnati in the media, calling the proposal "cheap politics." Scarnati fired back, citing Fitzgerald's ouster of former CEO Steve Bland as a "fiasco."

"[I]t is clear the policy set by the County Executive is not moving the Port Authority in the right direction," Scarnati added.

Fitzgerald has made no bones about his hands-on style. As City Paper previously reported, he previously required appointees to sign undated resignation letters — a practice he's since abandoned. At the Port Authority, he engineered Bland's ouster though the board was divided; Fitzgerald also considered naming then-board member Joe Brimmeier to the position. Brimmeier, the former CEO of the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission, was later indicted for allegedly directing turnpike contracts to vendors who donated to Democratic politicians.

Fitzgerald says he doesn't think those moves prompted the Act 72 overhaul. "Harrisburg has been a partner in transit for many years, but they're a partner without the seat at the table," he says. "That is unfortunate and I've supported the state having a seat at the table."

Scarnati's earlier proposal, he says, seemed to put the state at the head of the table. "What I was against then was the county executive had one pick out of 11 — somebody's got to be in charge of the system," Fitzgerald says. "We can't run an agency by committee."

State leaders credit Costa with brokering a compromise alongside state Sen. Randy Vulakovich (R-Shaler). But that doesn't mean Democrats are still fully happy with the bill. It passed out of the Senate 28-19.

Costa was among those voting yes: "If you work out a compromise you can live with, you need to support it," he says. While a number of Democrats had concerns about the legislation, "the bill was going to pass without our support, so I thought it'd be important for us, as much as possible, to have our imprint on it."

Democrats hope that having more Republicans on the authority's board will increase bipartisan awareness of transit needs.

"Like most marriages, there's going to be some potholes and we're going to have to work through them," says Brewster, the first appointee to the new board. "I'm not going to sit here and say it's going to be a perfect marriage, but a marriage it's going to be."