Toker aims to demonstrate that Fallingwater became a singular world-famous house by intent, not by accident. Furthermore, he argues that many persistent myths about Fallingwater just aren't true, so he sets out to dispel them. Like Frank Lloyd Wright himself, Toker reaches far beyond what is necessary for legitimate success.

There is an enormous amount of rigorous, even ingenious research in this book. Much of the writing is also quite compelling. When Toker delves into the history of the Kaufmann family and the Bear Run site, he brings both literal and metaphorical tributaries together in a dramatic narrative stream. Even before meeting Wright, "Kaufmann rejected the whole pompous image of the country house," Toker announces. "His lodge would stand unembellished before nature."

But like Bear Run, whose untrammeled appearance masks a history of human activity, Toker sometimes presents some previously visited ideas as fresh news. Then he adds excessive spin. The author states that Fallingwater, though dramatic, is less innovative than prevailing myths suggest: Wright adapted, even copied, works by Richard Neutra and Mies van der Rohe, among others, in designing the house on the waterfall. A less distorted version of this relationship has been standard American architectural history for 20 years. More recently, scholar Anthony Alofsin has addressed with particular depth and nuance how Wright absorbed and radically reconstituted lessons from his contemporaries. Yet Toker imagines the architect saying, "What if I replicate [Neutra's Lovell House] at Bear Run..." Why not quote Shakespeare, who surely said, "What if I replicate Plutarch when I write Antony and Cleopatra ..."

Toker takes his biggest leap -- only a metaphorical one -- from one of Fallingwater's cantilevers. It starts innocently enough, with the building's process of design. There is a long-standing myth, repeated even by recent historians, that Wright designed the entire house in two hours. Actually, author Donald Hoffman effectively refuted this tale in his 1978 book (which Toker footnotes but does not emphasize), so this myth is also less pervasive than it would seem. To Toker's credit, he researches even beyond the scope of Hoffman's admirable work and makes important new observations. To Toker's detriment, he bends his conclusions all out of proportion in an overzealous application of his thesis about PR.

Wright always claimed that he designed buildings in his head before ever putting a line to paper. Toker is the first to look at frequently published drawings and to state explicitly and quite correctly that Wright did not finish the design in his head; visible erasures on at least two drawings demonstrate that he was changing his mind significantly as he went along. (Toker publicly attributed the assessment to "one of my brighter graduate students.")

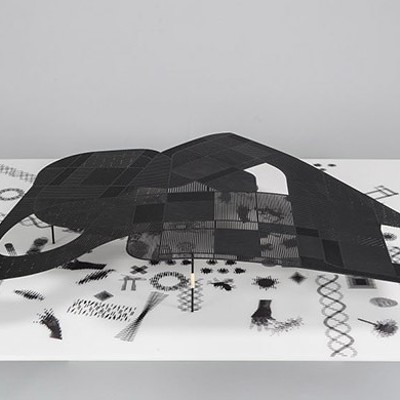

The observation about erasures is valuable and important, but the reconstruction drawing that accompanies it is not. Toker believes that Wright was going to design Fallingwater as we know it, but without an upper cantilevered balcony, as the speculative drawing shows. According to Toker, Wright added the upper balcony at the last minute, not to make more cohesive architecture, but because he thought it would get better PR.

But Toker here is trying to read Wright's mind rather than the real drawings and buildings. The original sketches contradict Toker's conclusion at all levels. The visible erasures show changes in numerous features of the house, not just that particular balcony. In one drawing that Toker mentions but does not publish, the upper balcony is there, but much of the lower balcony is missing. So the speculation is demonstrably incorrect as well as ill-advised. We can't pull incomplete designs from Wright's head so easily, and certainly not this one. Why spoil quality research with imaginary quotes and designs?

It seems that Toker has let a headline-grabbing image (which the illustration accompanying this article admittedly indulges) distract him from his craft. To say that Wright gave Fallingwater its upper balcony purely for PR purposes is a myth. In reality, PR may be the reason Toker took it off.