When Henry Clay Frick died in 1919, he gave the city 151 acres of land, and a $2 million trust to create and maintain a park. The city park that bears his name has since grown to encompass 644 acres, making it Pittsburgh's largest. But Frick's original bequest, now called the Frick Woods Nature Reserve, has largely remained a wilderness area, filled with native plants for locals to enjoy.

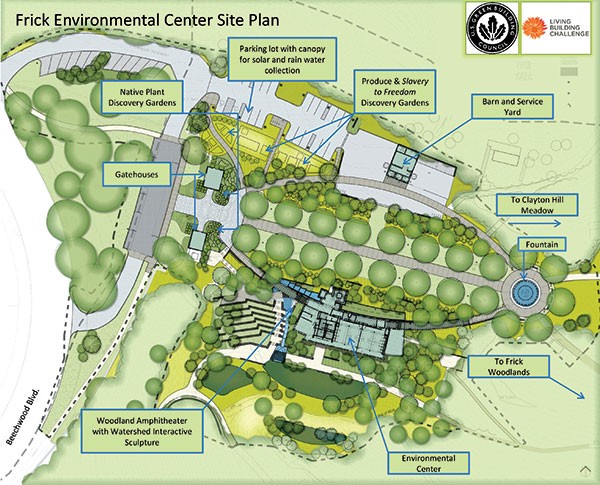

If all goes as planned, two years from now the reserve will also be home to a new environmental education center, complete with a redesigned parking lot featuring a canopy for solar and rainwater collection.

The new Frick Environmental Center, planned by the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, has been designed to meet cutting-edge environmental standards, including the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Platinum certification and the Living Building Challenge. The green facility will be net-zero energy and water, feature a geothermal heating and cooling system, and include recycled wood.

But critics are saying the greenest thing the conservancy could do would be to build the center somewhere else. And they wonder whether increasing environmental awareness is more valuable than protecting the environment itself.

"I see a beautiful wilderness that's going to be bulldozed to build a nature center," says longtime park patron Harriet Stein, who lives in Hazelwood. "You can't bulldoze a park to build an institution, and plant some trees and say that's good enough."

The new $15.9 million center will serve as a hub for programs like youth summer camps and other special events. It will contain classrooms, public restrooms, offices for the center's staff, a reception area and a 60-to-80-seat amphitheatre. The new center will be located near the Beechwood Boulevard entrance the park, on the site of the old Frick Environmental Center, which burned down in 2002.

But construction, which is anticipated to last two years, will affect approximately 10 acres of the park, though only five acres will be closed off by a fence. A portion of the park, including some trails and a nearby parking lot, will be closed during that time. Building the structure will require cutting down 95 mature trees and uprooting countless wildflowers. PPC has already begun relocating some of the wildflowers, and plans to plant some 195 trees, doubling the existing population.

Even so, and despite the fact that the new structure would replace an old one, critics worry about the impact. Stein says newly planted trees could take as long as 80 years to mature, and construction of the facility will disrupt wildlife habitats.

She and several other Frick Park patrons worry about the impact of an influx of students: Stein says increased school-bus traffic will detonate a "diesel bomb" in the area.

While Stein applauds the work the environmental center has done with youth over the years, she says the PPC is looking at economic benefits of the development (like providing jobs to construction workers) instead of how the center will impact the Frick Woods Nature Reserve.

"I think everyone thinks this is a good idea, because they're not looking at the bigger picture," Stein says. "It's a capitalistic enterprise disguised as environmentalism."

PPC acknowledges there will be some environmental costs: "It's challenging to see so many trees taken out; it's hard, admittedly," says Marijke Hecht, the Conservancy's director of education. "Unfortunately it's impossible to do a construction project without removing some trees."

Still, she says, she can't see how the center could be viewed negatively.

"Environmental education serves so many functions," says Hecht. "It provides a hands-on way for kids to understand the world around them. All of our programs have some stewardship component. The kids are planting trees; they're helping to curb erosion."

Since the original center burned down, the center's staff has continued to run a variety of educational programs for youth in the park, but needs more space to expand the programs to more participants. What's more, Hecht says, the facility will be a model for green building. There are only five "living buildings" in the world. In order to qualify, the building must be constructed from environmentally safe local materials, filter and treat all waste water, and use 40 percent less energy than similar buildings.

"Especially early [on,] the biggest concern we heard was footprint. Because [the site is] so wild-feeling, a concern we heard is how is it going to feel," Hecht says. "But our footprint is slightly smaller than the original building, and we have more usable square feet. We were trying to be as light as we can. What we wanted to do is make it small, so we're not taking a lot of land."

Hecht says while the new facility is nearly the same size as the old 11,000-square-foot center, an additional floor and outdoor "classrooms" boost it to about 15,000 square feet. And, she says, the value of inspiring youth to be more environmentally conscious outweighs the cost.

"We are planting not only more trees than we're removing, but we're also improving the bio-diversity there" by planting different species, Hecht says. As for the trees being lost, she says, "We're working with a couple local craftsmen to ensure we're reusing the wood."

PPC sent out a request for proposals in April, but Hecht says the bids they received were too high and her organization is trying to rework the design to stay within their budget. Currently PPC only has $8 million for the project and predicts the first phase will cost between $5 million and $6 million.

In August 2013, Pittsburgh City Council voted to use $5 million from the $16 million Frick trust for the project. City Councilor Corey O'Connor, who represents neighbors of the park and chairs the council committee with jurisdiction over parks, says council is unlikely to delay construction of the new center, which is set to start this summer.

"I believe everyone's happy to get the center back up and running," O'Connor says. "Unless there was going to be harm to residents, I can't see wanting to stop a center that's going to benefit kids and the community."

Similarly, the city's parks and recreation director, James Griffin, expects city administrators to sign off on permits needed for construction.

"It's an asset that's going to be tremendously valuable," says Griffin, who previously worked for PPC. "The vast overwhelming majority of people support it."

Both men say they've heard from more residents in support of the environmental center than from opponents, though plenty of concerns have been raised on the 205-member "Occupy Frick" Facebook page. Among the page's active members is Dennis Sullivan, who believes the environmental center could be housed in a building bordering the park. He likes the idea of adding amenities to the park, but says the proposal is too large because it also utilizes outdoor space for classrooms.

"I'm not sure it's the best use of the park," says Sullivan. "I like the idea of a nature center and restrooms, but I think it needs to be scaled back in scope."

Sullivan says he's also concerned with the lack of transparency in the planning process. Neither he nor other members of the Facebook group, he says, were aware of a chance to weigh in on the project other than a public meeting in April.

"There didn't seem to be sufficient public input," Sullivan says. "My request would be to slow the process down."

Hecht disagrees, saying the design process has been three years in the making, and has involved more than 600 people who provided input through workshops at the site, focus groups and meetings with key stakeholders. Among those groups were local environmental nonprofits, schools and community organizations like the Squirrel Hill Urban Coalition and the Regent Square Civic Association. Throughout the process, Hecht says, community feedback has been overwhelmingly receptive to increasing environmental education at Frick Park.

"We have serious environmental issues that need attention," Hecht says. "We can't expect to see more environmental change if we don't get people engaged. To have some small cuts for the larger good of engaging hundreds more children is what motivates us. We want to see those children grow up to love Frick Park."