The indomitable protagonist of Jean Pierre Jeunet's Micmacs might strike a stranger as having a screw loose. Quite the contrary: He's got an extra piece of metal in his head.

You see, very late one dark Parisian night, while he's working in a lonely video-rental store and watching a Bogart movie -- precisely lip-synching every word of Bogey and Bacall's dialogue -- a scene from a real-life movie suddenly takes place outside: A car and a motorcycle, bullets a-blazin', come screeching by, and a stray bullet lodges in his skull.

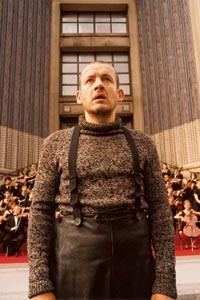

If the doctors take it out, they might leave Bazil (Dany Boon) a vegetable, so they send him home to -- well, pretty much nothing. His indifferent boss has replaced him with a chippie, and soon he can't afford a place to live. So he becomes a street performer, gathering enough change to get by.

That's enough of a premise for a character study, but in the hands of Jeunet, the furiously imaginative Frenchman behind Amelie and City of Lost Children, it's just the beginning. First, 30 years ago (in the movie's faux-triste prologue), Bazil's father dies doing his job of defusing land mines in a war zone. Then, the homeless adult Bazil joins a coterie of eccentrics who live in a sort of tunnel-factory under a mountain of junk at a scrap yard.

The central figure of this gang is an artist who uses found objects to create mechanized sculptures. There's a woman, the daughter of a seamstress, who can look at something and instantly deduce its dimensions; a surveyor from the Congo; and a contortionist who developed her skill as a way to hide in an ice cooler from her abusive father.

"I'm not twisted," she tells Bazil, on whom she has a crush. "I'm a sensitive girl in a twisted body." That, I'm afraid, is what passes for the whimsical and the profound in Jeunet's unbearably creative movie.

But there's more. When Bazil stumbles upon the two companies -- located across a street from each other -- that made the weapons that killed his father and entered his skull, he devises a convoluted plan to ruin them that's at once ingenious and haphazard. When his colleagues catch on to his scheme, they give him an angry ultimatum: Ask us to help you, or get out. More profundity here: We're all in this together, despite (or because of) our quirks and differences.

Needless to say, the companies are ultimately ruined, and the boy gets the girl. But in Jeunetville, nothing is quite as important -- not war, not child abuse, not love and longing -- as making a movie that's as flamboyantly visual and offbeat as possible. The same goes for the performances he demands of his actors: Everyone in his exceptional cast is elastic and bombastic, albeit thoroughly one-dimensional and therefore rather monotonous. Micmacs is pure cinematic pleasure if you like this sort of thing, and a roaring bore if you don't.

At the heart (but not the brain) of Jeunet's tale is an anti-war farce, the sort of well-intentioned thing we get from time to time. But what makes Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove a masterpiece and Jeunet's Micmacs more a piece of creative masturbation? Kubrick took a single, plausible idea and explored it with singular, plausible characters -- all of it gradually stretched to the point of absurdity. Jeunet begins with contrivance and plunges right in. The result strikes me as being merely self-indulgent, especially its allusions to classical cinema, including a musical credit to the great Max Steiner, whose symphonic strains swell up at some of the most melodramatic moments.

Toward the end of Micmacs, Jeunet treats us to some photographic spoils of real war and its effect on women and children. Boy, don't I feel guilty now for not liking his movie? But then it's back to feeling good, as Bazil and his gang complete their revenge plot, and the weapons magnates beg for their lives (always a pleasure to see, no?). "Rimbaud was a poet who became an arms dealer," says one of the malicious men. "I'll do just the opposite." Not if Jeunet has anything to say about it -- which he most certainly does. In French, with subtitles.

Starts Fri., July 9