T-shirts, pins, flags, bookmarks, notepads and bandanas. If it has a pink ribbon on it, there’s a good chance Pittsburgh-area resident Meghan Koziel has received it. In the year since she was diagnosed with breast cancer, Koziel says she’s been overwhelmed by the amount of pink-ribbon merchandise she’s received. It’s not that she’s ungrateful; Koziel just doesn’t find the breast-cancer symbol comforting.

“When I was diagnosed, everyone wanted to send me things with the pink ribbon on it,” Koziel says. “It was in my face constantly to the point that I felt suffocated by it. It’s wonderful to get gifts when you’re sick, but I have a box at home and everything with a pink ribbon on it, went in that box.”

Koziel isn’t the only one bugged by the popular symbol. The breast-cancer ribbon and the color pink have come under fire in recent years after advocates started questioning how money collected from pink-ribbon merchandise was being used.

But that won’t stop the barrage of pink clothes, grocery-store items and advertisements Americans are exposed to in October for Breast Cancer Awareness Month, in addition to personal statements such as men dying their beards pink. (In years past, Pittsburgh even colored the waters of the Point State Park fountain pink.)

Despite advertising efforts that present a united front, there’s little consensus within the breast-cancer community about the controversial ribbon and pink branding. Some organizations, like the American Cancer Society, embrace the pink movement full on. Other cancer organizations, like local nonprofit Glimmer of Hope, have never branded themselves under the pink label. And as for Koziel, while she might not be a fan of the breast-cancer ribbon, the color pink has always held a special place in her heart.

“My favorite color’s pink, so pink for me doesn’t really have a negative connotation,” she says.

But all agree on the need to ramp up the battle against breast cancer. An estimated 246,660 women in the United States will be diagnosed with breast cancer, and an estimated 40,450 will die from the disease this year.

In April 2015, 25-year-old Koziel found a tumor in her breast. At the time, she was told she was too young to have breast cancer, but returned to the doctor after it continued to grow and she continued to experience pain. At 26, she was officially diagnosed, and since then she’s documented her journey on social media.

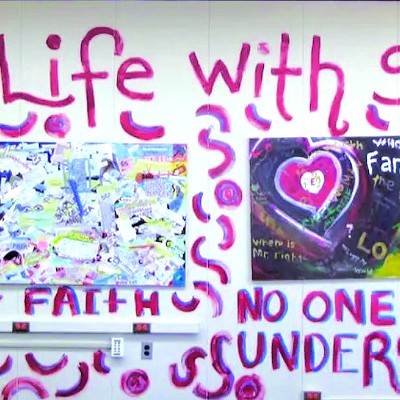

“When I was Googling mastectomy or breast cancer, you get all these scary, horrendous pictures of people that had all these terrible things go wrong,” says Koziel, who posted pictures of her naked chest on her blog and social media. “I feel like my scars tell my story, and I want other women to feel empowered by my posts, and not to be ashamed if maybe they don’t have nipples or they have mastectomy scars.”

But a lot of people weren’t happy with Koziel’s posts. The bubbly woman was subjected to vicious comments on the photos she posted on Instagram from people she’s never met.

“When I first came out with my first mastectomy picture, I had people write horrendous things about me — that I was ugly,” says Koziel. “But I think there are other upsetting things about cancer, not the scars that saved my life.”

And Koziel has received a lot of positive feedback as well. She set up a GoFundMe page to help pay for her treatment and has raised $21,709 to date. She recommends supporting those living with the disease in ways like this, instead of donating to nonprofits.

“It’s wonderful that the money is supposed to go to research, but there’s no way to track it,” says Koziel. “I don’t make donations, and I don’t recommend people to make donations to those types of companies. You should be raising money for people who are sick, to make it through life.”

For more than a decade, breast-cancer organizations and pink-ribbon merchandisers have been under scrutiny from activists questioning how funds are used. Among them is Breast Cancer Action, founded in 1990 by women living with and dying from cancer, who were dissatisfied with the inadequate treatment choices they had.

“A quarter of a million women will be diagnosed with breast cancer this year, just like last year and unfortunately probably next year. About 40,000 women die of the disease each year,” says Karuna Jaggar, Breast Cancer Action executive director. “We’ve just seen far too little progress for the billions and billions of dollars spent on pink-ribbon products, and far too little progress for the focus on awareness. We need action.”

According to Jaggar, the ribbon was originally created by 68-year-old Charlotte Haley who was using them to call attention to inadequate funding for research into the root causes of breast cancer. She turned down corporations looking to partner with her, so companies released a breast-cancer ribbon of their own in the pink hue seen most commonly today.

“From an early stage, the pink ribbon was a corporate co-optation of an activist’s peach ribbon,” says Jaggar. “They did these focus groups that found that pink was cheerful and soft and nonthreatening, everything that breast cancer is not. And the result was that when these companies turned the peach ribbon pink, they also shifted the focus from prevention to just empty awareness.”

Breast Cancer Action launched the Think Before You Pink campaign in 2002 to shine light on issues in the pink-ribbon industry. The campaign asks the public to consider where money collected from pink-ribbon products is going. The campaign also highlights pinkwashing, such as when a company whose products or services contribute to increased breast-cancer risk sells pink-ribbon products.