No evidence suggests Robert Wideman actually shot Nichola Morena, a used-car salesman, in 1975. But Morena was shot during a criminal scheme gone bad, one Wideman participated in. That made Wideman an accomplice to a felony in which a homicide occurred; under Pennsylvania law, that made him guilty of second-degree murder. The charge carries a mandatory life sentence.

Prisons are full of such stories, but Wideman's is better known than most. His brother, John Edgar Wideman, is a nationally renowned author. The elder brother wrote a book about Robert's struggles, Brothers and Keepers, which won a 1984 National Book Critics Circle Award in 1984.

Wideman's crime occurred late at night on Nov. 15, 1975. According to trial testimony, Wideman and two accomplices -- Michael Dukes and Cecil Rice -- agreed to sell Morena a truck full of stolen television sets. When they met on Morena's Saw Mill Run Boulevard car lot, it turned out there were no TVs. Instead, Wideman and his accomplices demanded that Morena turn over whatever money he had. When Morena ran, Dukes shot him in the shoulder. Morena kept running and eventually collapsed a few blocks away. He eventually bled to death.

Later, evidence emerged suggesting that Morena had gone without medical treatment for hours due to an overworked hospital staff. The Morena family won a wrongful-death lawsuit against the hospital. Upon hearing those developments, Wideman appealed his conviction, arguing that if a civil court deemed medical staff responsibile for Morena's death, Wideman's charges should be reduced. He recruited a key ally: former Allegheny County Coroner Cyril Wecht, who argued that in light of the new information, Wideman should have been charged with homicide -- not murder.

A judge granted Wideman a new trial in 1998. But Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr. opposed the retrial, and a three-judge Superior Court panel eventually disallowed it.

Wideman's chances for release now are slim. He is seeking a pardon from Gov. Ed Rendell, but only four such commutations have been granted in the past 15 years.

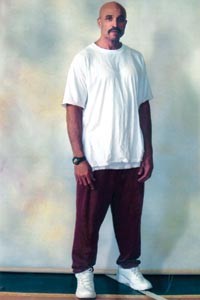

In the State Correctional Institution-Pittsburgh, Wideman lives in a small cell outfitted with a sink and a toilet, books, a typewriter, and an electric piano-keyboard and a television. He works 40 hours a week at SCIP's gym. He has been married twice, the second time in 1996, when he married a woman he met during an NAACP meeting held at SCIP. One of Wideman's sons was killed following a bar fight in 1993.

I am a reporter with the Innocence Institute of Point Park University, which reports on claims of wrongful conviction involving Pennsylvania inmates. In order for the Institute to investigate a claim, an inmate must claim "actual innocence" -- meaning that the conviction was for a crime in which he or she did not participate in any way. Since Wideman was involved in the stolen-TV scheme, he does not qualify for the Institute's help. I conducted this interview as a freelance journalist.

This interview was conducted over, and condensed from, several visits to SCIP during late 2009, and through several letters.

Do you think back to the night of the crime often?

You gotta remember, this happened 35 years ago. I thought about it for a long time -- about the people I had hurt and how I got into this situation. But day to day, you gotta live your life.

When I think about it, I think about how oblivious we were to what had gone on. We were running a con. We showed up with this empty U-Haul truck in a parking lot. Mike told Nick to give us the money, and Nick was angry. He thought we had a deal. He and Mike were yelling and saying all kinda shit, and Nick eventually dropped the money on the ground. It wasn't bound into piles in a briefcase like it is on TV: It was just a wad of $800. And it was windy, so I went to grab all the money before it blew away. Nick started running fast toward the road. I yelled "get him" -- not "shoot him" -- and Mike fired a shot. We saw Nick stumble, but then he got right back up and started running again. We just let him go. I didn't think Mike had even hit him.

What'd you do after that?

We went out drinking. I remember I got this feeling later on, though. I passed it off to the wine, but it was something more.

We were driving around downtown Pittsburgh. I started to get the shivers. I felt sick. I felt weak and fearful. I can't even describe it. And I remember Mike lookin' over at me like, "What's wrong?" I didn't say anything at the time, but I was horrified. I wanted to hide. I didn't know what to do, so I just wanted to go get plastered. I wouldn't find out until months later -- after we had been apprehended by cops -- but that shaking feeling, that fear, happened right around the time Nick died.

What's the most difficult part of being in prison?

I always thought the death of my mother would be the one thing I could not take. She died two years ago. She and I always promised each other that when I finally went free, she would be there to greet me when I got home.

Everything has changed in the last five years. My father passed, then my [two aunts], then my mother. When you're young, you don't think about all the things you'll miss behind bars. The worst of it is not really losing the freedom: The worst is knowing how much of your life -- and the life of everyone around you -- you are going to lose.

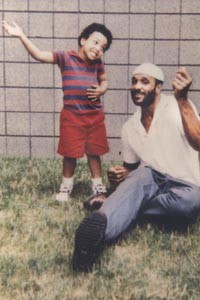

In 1993, when my son died, they let me go to the funeral home. But then I came right back here. I called home from time to time after that, but I just felt inadequate. I felt like I was just one more thing for them to suffer about. Not only am I in jail, but the whole family [is] in prison, too.

I have this huge family of educated people. My brothers used to give me books. My sister used to give me books. And when I started reading, I wanted to change the world. I remember I was in 10th grade when I read Malcolm X. I read Marcus Garvey, Ralph Ellison. The books impressed me. But my culture tore me away from all that.

What culture do you mean?

My family moved from Shadyside to Homewood. That's when I took a turn for the worse. I remember my mother saying, "I'm concerned about Robbie." She knew how rebellious I was -- always attracted to kids who were "always looking for trouble."

Maintaining a house in Shadyside in the '60s began to be more than [my parents] could handle. And my grandfather had a house on the edge of Homewood. He was willing to let us live there for little or nothing. My two oldest brothers, John and Otis, were grown and living on their own. So Mom and Dad and their three youngest moved into Grandpa's house, on Tokay Street in Homewood.

See, you had Shadyside, with all these white people around and book stores. People had money and the schools were good. Then you move over to Homewood: Everyone's black, no one has money and the schools ain't so good.

Not like that mattered to me. I was tired of being the only black face on the block. I was excited to be in an all-black neighborhood. And my mother was right: As soon as we moved to Homewood I got caught in the wrong mentality.

It was the '60s, and I wanted to do my own thing. The counterculture of the late '50s through the early '70s influenced me profoundly. I love the positives that era produced, but I got lost in the negative aspects of that idealism.

School and good grades were my brothers' and sister's way, not mine. In my mind, there was always some easy way out, some way to reject the system. It wasn't any sort of real idealism. I was irresponsible and did not want to work hard.

I didn't have to do this. I have abilities. I am intelligent. I just threw it all away. And it hurts. I wonder how I could've been so foolish.

What were you like when you first came here?

I was young, mid-twenties. I was so immature and caught up in my own images of who I thought I was and how people saw me. I thought I was making all the right moves and was out-thinking everyone.

But deep inside, in that alone place we all inhabit, I was in fear of what tomorrow would bring. I was angry and confused, unable to fathom how my life had turned out as it had. I never saw myself as a violent person. I had carried a gun at times, but I always thought it was for show. I rationalized if push came to shove, pulling the gun out would get me by. My ideas were not thought out very well.

I used [drugs] for a lot of years. When I came to prison, you could not even file for commutation until you had eight years, and no one made it the first time. At 25 years old, eight years seemed a long, long way away. I just about ruined myself with drugs and alcohol. And, man, drugs make me do dumb things.

So what changed?

Change for me came when I began to search within. I joined the Muslims, and then I moved on to other religions, but did not find the peace I was searching for. I had been trying to make deals with God: If I followed the words of whatever book, God would let me out of prison. I discovered God don't make no deals.

My studying of religion -- especially Eastern philosophy and its focus on karma and God's all-inclusiveness -- has given me a strong moral compass. It has also given me a certain connectedness to all people.

Nobody should get out of prison until they have done something to be a productive citizen. I think school -- or vo-tech, college -- instills this in people. ... It should be mandatory that each inmate should increase their level of education.

I've heard people say, "Why should we give inmates a free education?" You're spending the money anyway -- as much as $35,000 per year to house and care for inmates. Education would save money in the long run. You need to encourage these guys to learn something new. A lot of these kids come to prison and can barely read -- some can't read at all.

As it stands now, prison does not deter. In many cases, just being here is a badge of honor. If you reform the institution so people can -- and are, in fact, forced -- to learn and grow, I think you're going to have a much better, less violent society.

So why doesn't that happen?

The prison system is a political farce. It's perpetrated on citizens by politicians with blind participation from the media and popular culture. The American taxpayer is experiencing cuts in essential services like schools, hospitals and bridges while prison budgets skyrocket.

The public accepts these huge tax levies out of fear and a need for safety. But does it keep the public safer? What does the use of so much money for prisons say about us?

Don't get me wrong: Society needs prisons. I do not advocate for anarchy. What I advocate for is a smarter system based on the need, not on political gamesmanship.

You said the media is to blame, too. How so?

You see it every day, I'm sure: The 24-hour news cycle that reports the most heinous, most sensational, most disturbing crime over and over. This fear and need for change and justice puts a demand on the politicians to correct the problem. Typical solution? Spend more money and put more people in prison. America now has more people in prison per capita than any other country in the world. Has that made these senseless, heinous crimes go away? No.

People might suspect you have an ulterior motive for wanting to convince them of that.

Fine, don't believe me. I'm a prisoner who wants out of prison. That's fair. [But] nobody wants to talk about prison reform. We live in a time when so many pressing issues exist that people suffer apathy of partisan distortions. This leaves the old boys' network in place, and prison is the great gravy train that never runs out of money -- money that is passed around to constituents and cousins. The need to change becomes secondary to the need to hold control.

Is the justice system institutionally racist?

I don't want to alienate people. The politics of racism are so contentious and full of blind-spots that I shy away from the topic.

So, institutionally racist? I don't know that there was any grand plan to make it this way. But what can you expect? Most judges are white and affluent: How are they going to treat a black kid and a white kid when they come in on identical charges? In the white kid, the judge is going to see an element of himself, or his son or his grandson, and have a deeper empathy. He's gonna give the white kid a chance. Maybe he'll give the black kid a chance, too. But the numbers show he probably won't.

Things have changed: Obama's election said as much. Election night, I was joyous, just laughing and crying nonstop. But racism still exists. Disparities remain, in average lifespan, in education, in everything.

Has prison itself changed since you've been here?

When I came into prison in 1976, everybody used to carry knives, just to protect themselves. You would not look at anyone unless there was an invitation to do so. Even the slightest thing could get you beaten or killed. Men were meaner then. And there were fewer guards.

Back then, you had actual criminals in prison. [Now] we've incarcerated more and more people, hired more guards who'll write you up or throw you in the hole for doing nothing -- for talking back, for not getting out of bed in time. Until the influx of cocaine and crack offenders in the '80s, this was a place to incarcerate bad men. Now it's more like an institution -- much more populated, certainly softer, but no more humane or closer to solving the ills of society.

Do guards or other prisoners treat you differently because of Brothers and Keepers, and your brother's fame?

Around 1984, when the book was released, I was featured on 60 Minutes. Ed Bradley showed up and I took him on a tour of the prison. I was in newspapers and magazines. I would get tons of mail. Out of nowhere, it seemed like I was important. But that faded away.

Today, most people don't know anything about the book. It's in the library here, but it's very rare that it'll get mentioned. The other day at chow hall, someone yelled over, "Hey, Wideman! I liked the book." But nothing more than that.

Did the book harm you at all?

Some prisoners -- and some guards even -- wanted to bask in that light with me. Others took it as an invitation to hate me. But no one acted out in any really obtrusive way. I'm over 6'1" -- if someone was against me or the attention I attracted, it's not like they could just pick on me. Nick's mother has been in a lot of newspapers, on television, talking about how I should never be released from prison for what I did. I think that has played a great role in the numerous denials of my commutation appeals. But I've never had animosity toward her. I lost a son, too.

So why should you get a new trial now?

I'm not innocent of a crime, but I'm innocent of [second-degree murder]. In my [criminal trial], Wecht testified that the only evidence concerning cause of death was a gunshot wound. Twenty-three years later, Dr. Wecht testified that had he known of the [kind of medical care Morena received], he would have given different testimony. Dr. Wecht testified that he believed the testimony he gave at the trial was false and incomplete. So how can I be guilty of second-degree homicide when the essential element of causation was [based on] false testimony?

Well, you can argue Morena died because doctors didn't treat his wounds properly. But Morena wouldn't have needed a doctor if Dukes hadn't shot him.

If that's the way a jury feels, then so be it. But that doesn't change the fact that a jury has not heard the true evidence of causation.

In my opinion -- not that I suppose it matters -- but to me, 34 years has been long enough for the crime I committed. Especially considering that a jury had no opportunity to hear the true evidence of cause of death.

Ultimately, though, I need to live my life apart from the grievances I have with the justice system. To concentrate on nothing but appeals and court proceedings and whatever else would render me insane.

I am not sure if we grow because of or in spite of our circumstances. I guess it could be argued prison afforded me the time to look hard and deep for answers to those ultimate questions most folks rarely have time to pursue. Those endeavors sustained me over these years. Without them, who knows where I'd be?