Don't ask local activists or civil-liberties experts to pinpoint the worst excess of the "war on terror" since the 9/11 terror attacks. After a decade, they say, there are too many to choose from.

Random searches on public transportation. The surveillance and infiltration of Muslims. The demonization of protest and anti-government sentiment -- unless it comes from the conservative end of the spectrum -- and the use of terror laws used to prosecute activists. The creation of the Department of Homeland Security. The migration of military tactics to civilian policing. The continued operation of a U.S. prison in Guantanamo Bay -- not to mention the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that created it.

And those are just the tactics we know about.

"We don't know exactly what's going on," admits Brooklyn College Professor of Sociology Alex Vitale, who tracks government reaction to dissent for the New York American Civil Liberties Union.

That uncertainty may be the most disturbing development of all. Last week, for example, the Associated Press reported that the CIA and New York City police have been collaborating to monitor and infiltrate Muslim groups and mosque attendees. That's "very troubling," Vitale says -- both for what it says about local police and "for its implications for the CIA." The spy agency, after all, is supposed to confine its intelligence-gathering to foreign countries. "If the CIA is taking part in domestic surveillance by proxy …"

"There's been a whole range of ways in which the country has gotten more repressive," adds Jules Lobel, professor of constitutional law at the University of Pittsburgh and vice president of the U.S. Center for Constitutional Rights. "It's become more easy for the government to take repressive actions like racial profiling." And the courts' refusal to hold the government accountable either criminally or civilly "could have bad effects on the country for years to come."

Over the years, there have been high-profile arrests involving people accused of hatching terror plots. But in cases ranging from Oregon to Baltimore, undercover agents have arguably acted as provocateurs, even supplying fake weapons to would-be terrorists, whose plots agents themselves have sometimes described as "aspirational," rather than genuine threats. Such practices are "basically weakening the restrictions on police use of entrapment," Vitale says.

Activists say some of these trends predate 9/11. But the past decade, they say, has seen unprecedented victories for security over free speech.

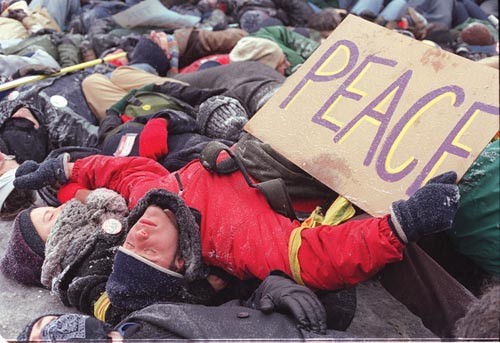

"What limited democracy exists in the United States has evaporated since 9/11 at an alarming rate," says Naomi Archer, a national activist who joined the protests against the international G-20 summit here in September 2009. Thanks to increasingly heavy-handed restrictions on public demonstrations, she says, "People's space -- for action, for thought, for creative [expression] -- has shrunk. What the state considers an acceptable level of expression has shrunk."

The government has sought to shrink dissent's physical space as well, Archer notes. "Their whole basis for [policing] is to keep a critical mass" from gathering. "Unfortunately, the left hasn't been able to break out of their paradigm to do the things necessary to stop that."

The climate of fear, magnified by the shouts of right-wing television commentators blasting the motives and loyalties of those they disagree with, "reminds me a little of Nazi Germany, where you also had to be fearful of the stranger," says Edith Bell, a veteran local activist with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. (Unlike the right-wing talkers who sometimes invoke the Holocaust, Bell was born in Germany and survived several concentration camps.)

"Sometimes it's almost difficult to remember how much things have changed," says Joyce Wagner. On 9/11, she was 17. Since then, she has been to Iraq twice with the Marines -- and is now board co-chair for Iraq Veterans Against the War. "The scariest thing is how many of these things -- just the security culture -- have become usual to people my age."

"When I look at the types of actions taken by the government since 9/11 -- many of which have been challenged in the courts, and the challenges have failed -- I never would have believed it before 2001," says Vic Walczak, legal director for the ACLU of Pennsylvania. "The damage the Supreme Court is doing is not just saying, 'You lose on the [basis of] the law' but, 'You can't challenge the law.' They find some sort of immunity" for the government agency being sued.

For instance, after 9/11 the ACLU was unable to successfully sue the government for detaining people without charges; the government identified detainees instead as "material witnesses" to crimes it never revealed, and courts declined to overturn the designation.

Walczak cites the case of Abdullah Al-Kidd, a U.S.-born Muslim convert detained in 2003 for 15 months without explanation, whose lawsuit was only recently kicked out of court. Or the case of Egyptian native Abdel Moniem Ali El-Ganayni, who lost his security clearance at the Bettis laboratories here and could not work.

"For the first time in history, [the government] said they couldn't even tell him why they revoked his security clearance" -- a refusal itself attributed to purported security concerns, Walczak says.

Civil libertarians have enjoyed the occasional victory. Walczak cites a lawsuit that got Muslim airline pilot (and Iraq War veteran), Erich Scherfen, and his wife off the no-fly list -- an obvious job-killer for a pilot. Walczak recalls asking Scherfen's wife whether any of her friends were also on the no-fly list.

Her answer, recalls Walczak: "Yeah, everyone I know."

Everyone she knew from their mosque, that is. "She looks at me and says, 'Don't you have a lot of friends who are on the list and have trouble at airports?'" Walczak recalls. "And I said, 'No, I don't.'"

Saleh Waziruddin, a Canadian Muslim who spent the initial post-9/11 years in Pittsburgh working and joining in protests, still isn't sure why he was detained temporarily at the Canadian border when trying to re-enter the U.S. in 2004, or why he was barred from coming here entirely for five years beginning in 2006.

"It could be something as simple as writing a letter to the editor against what the FBI is doing, or participating in a demonstration," he says today. "Somebody put me on a list. I don't even think it is possible to find out why. If there had been an informed reason to deport me, I think they would have asked me [about] specific charges."

Prior to the start of the Iraq war, in March 2003, there was a degree of cooperation between Pittsburgh's FBI and the local Muslim community. Waziruddin says he attended a meeting between Muslim leaders and local FBI and immigration officials here.

During that meeting, Waziruddin recalls, an FBI representative "said that he was a Marine who fought for the right for free speech in this country." But in the same breath, the agent added "that if someone opposes the war they could be a violent supporter of Saddam Hussein and so should be investigated."

Anti-war activists say that they, too, have failures to answer for. After all, the left has largely failed to stop the government's post-9/11 moves, despite a rise in activism not seen since the Vietnam War.

"The legacy of the anti-war movement is not a good one," says Tim Vining, who headed the Thomas Merton Center from 2001 through 2005. The Garfield-based group was at the center of mass anti-war organizing here, but Vining says its efforts suffered from insularity.

"The leadership of the anti-war movement is dominated by religious pacifists whose message does not at all resonate with the American public" -- especially, he believes, with the African-American and other minority communities who are not widely represented in peace movements here.

"We have failed to reach the very people the war has most directly impacted -- the working and lower classes," concurs Francine Porter, local coordinator of Codepink Pittsburgh. "We have failed to make the majority of people realize the importance of keeping billions of dollars that could support social programs and much-needed human needs in this country instead of going to war."

Differences over tactics also fractured the anti-war movement, says Alex Bradley, a vocal presence in Pittsburgh for most of the decade with the anarchist Pittsburgh Organizing Group.

The mainstream left, with which POG once cooperated on a limited basis for certain anti-war actions, "couldn't articulate any strategy beyond permitted mass marches and lobbying politicians," says Bradley. "They thought that if the population turned against the war it would end."

In fact, polling data suggests a majority of Americans began questioning the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan long ago. Yet the wars continued; when Democrats scored huge electoral gains in the 2006 elections, George W. Bush responded by expanding the war effort in Iraq.

Says Bradley, "This lack of understanding of how power operates meant [peace activists] had no idea what to do, once most people agreed with them but nothing was changing." Too often, he says, moderates engaged in "a really problematic retreat" into the "false notions" of patriotism and the seeming respectability of being accepted as legitimate by the mainstream media.

If anything, some activists say, election-year gains may have hurt the cause. "A terrible thing happened to the anti-war movement: Obama was elected," says Porter. "Many on the left helped put him in office. Many were hesitant to go out in the streets and oppose him, even though the war dragged on, and the promises he so eloquently spoke of during his campaign were not kept."

Pete Shell, head of the Merton Center's Anti-War Committee, says that in the end, some in the movement proved to be more anti-Bush than anti-war. But he's not ready to give up.

Shell just returned from a meeting in Chicago, where he spoke to organizers preparing to counter a meeting of the G-8 and NATO there in May. The results of such protests may not be immediate or obvious, he says. "However, I believe that if it weren't for the anti-war movement, the U.S. government may have invaded additional countries in the Middle East after invading Iraq."

To Mary Sheehan and Gail Austin, at least, the anti-war movement remains viable. Each is a stalwart at weekly street-corner peace vigils held by Pittsburgh North People for Peace and Black Voices for Peace, respectively.

"We try to take a long-term approach," says Sheehan. "We have to get beyond protesting one war after another to try to work to change the mentality to peace being a way of life."

"The wars are still going -- that's what keeps us going," says Austin. "The only other choice is to do nothing. And no change comes from that."

Edith Bell, for one, has no patience for people who sit back while others protest. "What is the anti-war movement?" she asks. "It's volunteers" -- volunteers whose work is often ignored. "We have some hard-core people working and the rest of the people say, 'Oh, it's great what you're doing.' I have no patience for that. Why aren't you in the streets? If we don't get millions of people in the streets, we can't change [anything]."

And if millions did turn out, she contends, the message wouldn't be ignored anymore. "Right now there have been people at the White House [gates] protesting the pipeline" that, if approved by Obama, would carry oil from Canadian tar sands through the U.S. The protests are motivated by environmental concerns, especially misgivings that exploiting the tar sands would release huge amounts of greenhouse gases certain to worsen global warming. Hundreds have been arrested so far, Bell notes, but the demonstration has been ignored by most news outlets.

Even as she waits to be arrested at the White House fence, national direct-action organizer Lisa Fithian sees the future of activism in local issues. Fithian helped organize here during the G-20 summit in 2009, but recently she has spent much of her time training activists to tackle problems specific to large cities across the country.

"All of those groups are gearing up for a fall of action," she says. "The impact [of wars] is no less [now], but people are dealing with more immediate crises."

Those who are still active against the wars, meanwhile, have changed their tactics. Wagner, of Iraq Veterans Against the War, says her group is organizing near military bases "to stop the redeployment of traumatized troops" with post-traumatic stress disorder or traumatic brain injuries.

"My hope is that we're not looking at a dead movement," she concludes, "but at a movement that needs to reassess itself."