If you asked Pittsburghers to name the city's most important steelmaker, most would probably answer Andrew Carnegie, or H.C. Frick. Mention the name Charles Schwab, and most would ask, "You mean the guy who started the brokerage firm?"

Well, no. This Schwab is the guy who took over the Homestead Works in 1892, cleaning up the mess left by Frick's notorious lockout. This is the guy whose after-dinner speech led to the formation of U.S. Steel. He's also the guy who, after running afoul of the bean-counting corporate management he helped create, left U.S. Steel to preside over one of its chief rivals: Bethlehem Steel.

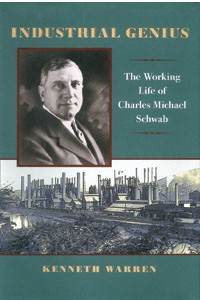

Kenneth Warren's book Industrial Genius is an attempt to give Schwab his due. As Warren convincingly argues, Schwab's creative zeal helped make a success of the American steel industry. Like Carnegie, Schwab plowed profits back into the company, constantly diversifying its products and improving its processes. (For that reason, Schwab's early departure from U.S. Steel is ominous: Decades later, Pittsburgh's steel industry collapsed partly because it failed to invest in newer technologies -- the kind Schwab insisted on developing.) Carnegie and Schwab were also consummate salesmen and charismatic optimists. They were spokesman not just for their company or their industry, but for a vision of American industrial greatness.

Unlike Carnegie, though, Schwab never aspired to be more than a steel man. As Warren writes, for "all his business talents and attractive human qualities, Schwab was a limited man" with little interest in culture or philanthropy. "For want of something better he was forced to seek distinction by remaining a master builder of businesses."

Warren's book suffers from the same limits. It closely studies Schwab's business moves, but gives little sense of who he was off the clock. Most of Warren's prose lacks Schwab's wit, and he often dwells on minutiae. For example, take Warren's account of Schwab's 1900 University Club speech on consolidating the steel industry, an address which led to the creation of U.S. Steel. Schwab began with a joke about how he'd keep the speech short, because his audience was made up of "old men [who] have to go home early." Warren seizes on this line to calculate the average age of Schwab's listeners. It was 61.9 years, in case you're curious -- but like any attempt to explain a joke, the disclosure falls flat.

Of course, as the title warns us, this is an account of Schwab's "working life." So it's no surprise that Warren barely mentions Schwab's adultery-riddled marriage until page 209. Even then he holds his nose: "It is not easy but fortunately [it] is unnecessary to write at length of their life together," he asserts.

Casual readers, at least, may wish Warren had similar qualms about discussing ore shipments. Such readers would be better served by 1975's Steel Titan, a livelier biography written by Robert Hessen.

Hessen's book has its flaws: As Warren points out, Hessen was a devotee of Ayn Rand, the high priestess of capitalism. As such, Hessen often sees Schwab in the best possible light, largely attributing labor trouble to PR gaffes. By contrast, Warren's account of Schwab's labor practices is more objective, and makes clear that Schwab could be ruthless. (He cites, for example, a letter in which Schwab exclaims "the labor situation could not be in better shape" -- just after he tells of firing a man for "sulking" on the job.)

Still, Hessen spends more than 10 pages on a scandal involving a contract to sell armor plating to the Navy. That scandal haunted Schwab's career, but Warren dispenses with it in a few paragraphs. For that reason and others, Warren's book is best read as a supplement to Hessen's. Warren corrects the record here and there, and fleshes out some additional data. But like Schwab himself, Warren focuses on business details, so much so that the book's significance is best appreciated by insiders.

Warren is forthright about this: His preface acknowledges the debt to Hessen, and notes that in writing the book, "[I]f I had anything new to contribute, I considered it worthwhile to do so." Scholars might agree with that assessment; general-interest readers won't be so sure.