At 6 p.m. on a late-summer day in 2011, in a slum in the Álvaro Obregón district of Mexico City, the garage on the bottom floor of Alma Brigido’s cinderblock home was set ablaze. The Brigido family had recently renovated the garage into a bedroom for Alma’s grandmother. The bed, the furniture and the television were engulfed by flames and smoke. The blue-painted iron garage door was turned black with soot.

The structure wasn’t just her home. Alma used one room of the house as a makeshift convenience store selling candy and other items to neighbors in the barrio. That’s where she was when she saw the flames. She panicked, but a neighbor ran across the alley with a hose and extinguished the blaze. Luckily, her two young daughters, Luz and Samantha, were spending time with her in the store that evening, even though they normally watched television in the renovated garage. No one was hurt.

“By the miracle of God, I took them with me to the store,” says Alma in an interview with City Paper.

Earlier that year, Alma’s partner and the children’s father, Martín Esquivel-Hernandez, had joined the Mexican army, after his employer, German-based tool manufacturer Stihl, moved its offices out of the region. He was in basic training for the Mexican army when the fire was ignited; once he completed his training, Martín was set to travel from state to state looking for and taking down drug cartels.

Unfortunately for Martín’s and Alma’s families, the drug cartels already had a presence in their Mexico City neighborhood. Alma believes a local cartel started the fire as a way to intimidate her because of Martín’s involvement with the army.

Martín’s brother, Arturo, told Alma “you really shouldn’t be here, you should be living with us.” So she packed up her things and moved Luz and Samantha to the house he shared with Martín in the adjoining Jalalpa neighborhood.

But the harassment and violence continued. A few months later, members of the cartel threw rocks at the house, demanding to see to Martín, but he was still in basic training. There was nowhere to turn for help. Residents of neighborhoods like these in Mexico City are typically left to their own devices; authorities tend not to serve the slums.

“The police do not come into these neighborhoods,” says Alma.

A week later, Martín was given a vacation, and he and Alma took the kids to Puebla, a city two hours southeast of Mexico City. This was when the cartel got serious. One night during the family’s vacation, Arturo came home and blasted some Mexican folk music on the radio — something Martín did every night when he returned home, but not something Arturo did regularly. Alma believes the cartels possibly took the loud sounds of trumpets and accordions as a sign that Martín had returned.

At night, the Esquivel-Hernandez family secured its door with lock and chain, but during the day usually left the doors unlocked. Because it was still early evening, a group of men entered through the front door and grabbed Arturo, as his pregnant wife and children watched in fear. Arturo wrestled away and grabbed a knife. A brawl ensued and Arturo ended up cutting one of the cartel members on the head. Some blood spilled on the kitchen tiles, but no one was seriously hurt and the gang retreated.

When the couple returned home and heard the news, Martín was furious. “I am just trying to do the right thing,” Alma recalls him saying back then. “This shouldn’t be happening to us.”

Regardless, both realized this was the time to leave: Their home and their neighborhood were no longer safe for them.

“I was not going to risk anything happening to my family,” says Alma.

Martín’s mother had moved to Pittsburgh in 2005; in 2011, the family decided to join her there.

Five years later, Martín Esquivel-Hernandez, an undocumented immigrant, sits in a private prison in Youngstown, Ohio, charged by federal officials in the U.S. District Court of Western Pennsylvania with felony illegal re-entry. Martín had unsuccessfully attempted to enter the U.S. four times; prior to his detainment, he had lived in Pittsburgh since 2012, with his wife, Alma, his two daughters and his son Alex, an American citizen.

This past March, Esquivel-Hernandez had been cited by Mount Lebanon Police for driving without a valid license. (He presented his Mexican license.) About a month later, at 6 a.m. at his Pittsburgh home, he was picked up by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers. The day before, he had marched in an immigrant-rights rally holding up a sign with his two daughters that read “Not One More Deportation.”

Martín has no criminal record. He has spent his years in the Steel City volunteering for local Latino community groups, advocating for better Spanish-language services at Pittsburgh schools, and fighting for other immigrant rights, all while working in the residential-construction industry.

“I can testify to his character,” says Rosamaria Cristello of the Latino Family Center. During the county’s process of assessing the needs of the Latino community, Cristello struggled to find volunteers willing to conduct a meeting with Latinos in Natrona Heights, but said that Martín and Alma jumped at the chance “without hesitation.” No one showed for the community meeting, but Martín and Alma stayed the required time anyway.

City Paper first reported this story in June, after witnessing a teary-eyed Martín being read his rights in an empty courtroom in the U.S. District Court building on Grant Street, in Downtown Pittsburgh. After his arrest by ICE, he was taken on a 665-mile journey to York County prison in Southeastern Pennsylvania, back to U.S. District Court in Pittsburgh, then to the Cambria County Prison, near Altoona, and eventually to the private prison where he currently resides in Youngstown.

During his initial arrest, his family had no clue where he was being taken and Martín had no way of communicating with them. So, during his arraignment in Pittsburgh, no family or friends were present to comfort a distraught Martín, even though they lived just miles away.

Martín’s story is far from unique. According to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), illegal re-entry has been the most common federal criminal charge from 2011 to 2014, even as deportations decreased over that time span.

Martín originally entered a plea of not guilty, but was set to change his plea to guilty on June 21. His family and friends convinced him otherwise and now he is fighting back.

Had he pled guilty to the federal felony charge, like many other undocumented immigrants he would have not only been ruled ineligible to ever become a U.S. citizen, but would also have been transferred to the deportation hub at York County Prison, where he would’ve received a hearing with an immigration judge via video conference, and then most likely been shipped back to Mexico, all within the span of a couple months.

But Martín still faces monstrous odds. According to U.S. Court data, of the more than 17,600 illegal re-entry cases seen from March 2014 to March 2015, fewer than 1 percent saw a trial and only 365 cases didn’t end in a conviction. Also, local law enforcement collaborated with federal immigration officers to detain Martín. Moreover, by making him a priority, those immigration officers appear to be going against orders, even as state lawmakers, federal elected officials, and even presidential candidates seem to be launching attacks against undocumented immigrants like Martín. On top of that, Western Pennsylvania’s U.S. Attorney is mounting a serious case against him.

If he loses and is deported, he might have to retrace the steps of his hellish 5,000-mile, nine-month journey. He might have to relive the four apprehensions by border patrol in two different states; feel the cockroaches crawl across his face again while sleeping in abandoned homes; rewash the cars in Mexican border towns just to make a few pesos; and again walk the hundreds of desert miles just to see the wife and family he fought so hard to reunite just four years ago.

“I came to the United State for a better life for myself and my family,” wrote Martín to CP in a letter from prison. “I could not defend myself and my family from violence. I was looking for the American Dream. But, the dream I was searching for is now a nightmare that I cannot seem to wake up from.”

“From the moment I arrived in Tijuana, I never stopped praying.”

tweet this

When Alma and Martín chose to emigrate to the U.S., they first visited the American consulate in Mexico City and told them about the fire and the harassment by cartel members. American officials told them they could apply for asylum papers, but Alma and Martín knew that would take time they felt they didn’t have.

So, they decided that Alma, who was now pregnant with their son, Alex, would cross the border with Luz and Samantha first. Martín elected to resign formally from the army because he didn’t think it was right to simply abandon his duty, Alma says.

So Alma, Luz and Samantha boarded a plane to Tijuana. Once there, they were aided by a coyote, a person paid to help immigrants cross the border undetected. The coyote supplied Alma with a legal ID to use to cross the border. Luckily for Alma, the photo on the ID looked almost identical to her. The 4-year-old Luz’s head was shaved, and she was placed in a diaper and a stroller to give her the appearance of a toddler.

“From the moment I arrived in Tijuana, I never stopped praying,” says Alma.

The next day they attempted to walk across the border at the designated pedestrian bridge near U.S. Interstate 5. Alma was stopped and asked for her papers by a border-patrol officer. She showed the agent her ID and the agent said “bye” and ushered her quickly through. Luz and Samantha were in line 10 places in front of Alma with the coyote and crossed without issue. They were almost safe.

After getting across the border, the family walked briskly past seven stop lights in three minutes. At a house in San Ysidro, Calif. they entered a car that was to drive them to Alma’s aunt’s house in San Jose. “Don’t look at our faces,” the men driving the car said to Alma and the kids. Once on the highway, they crossed the second immigration checkpoint in San Onofre, Calif., about 100 miles north of the border, without incident and they were home free. To this day the three remain undocumented.

For Mexican immigrants like Martín, entering the United States legally is a process filled with barriers.

In 2011, when he first attempted to enter the U.S., there were almost 1.4 million Mexicans on the waiting list to immigrate into the states; less than two percent of them were given visas that year. Applications on the wait-list went back as far as 1992.

“Our immigration system is incredibly convoluted,” says Sundrop Carter, of the Pennsylvania Immigration and Citizen Coalition. “The only good avenues for green cards are through family unification, but these are very limited and only apply to the nuclear family.”

And immediate family members must already be U.S. citizens. Martín and Alma have family in the U.S., but only their son is a legal citizen. Because the couple lacked any immediate family members who were U.S. citizens before immigrating, entering legally was nearly impossible, says Carter. She adds that even for those lucky enough to fit the legal criteria, the process can take five to 15 years just to get the initial green card.

Legal immigration is easier for those who have jobs lined up with employers willing to go through the green-card process. First, a U.S. employer must complete a labor certificate for the immigrant; this can take anywhere from six months to several years. Next, a visa petition must be obtained for the worker; this can take up to four months. Lastly, the worker’s green card must be obtained; this takes about six months. But Carter notes that this process isn’t perfect, saying that many employers, particularly in agriculture, have publicly supported immigration reform because of the difficulties of obtaining visas.

There are also visas for those who can prove worthy of asylum status, which Martín’s advocates are pursuing given his dealings with the cartels in Mexico City. And there is a lottery that makes 55,000 green cards available to persons from countries with low rates of immigration to the United States. However, immigrants from Mexico, China, the Philippines, India and others with high levels of immigration here don’t qualify.

Martín’s best path would have probably been to go through his son, Alex, who was born in California, in 2011. The U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services website says U.S. citizens are allowed to petition for permanent resident status for immediate family members (spouses, parents and children) to “promote family unity.”

But critics, who call children like Alex “anchor babies,” say this leads undocumented immigrants to give birth to children on U.S. soil simply to avoid deportation. In 2010, politicians in many states launched the effort to end birthright citizenship for children of undocumented immigrants.

Regardless, it would have taken two decades before Alex could even start this process to petition for Martín to enter the U.S. legally: Alex can petition for his father to enter the U.S. with a green card only on his 21st birthday, due in 2032.

For Mexicans who grew up in neighborhoods like Jalalpa, where Martín grew up, the pull to the U.S. is just too strong to wait.

Horacio Ruiz, a server at the Capital Grill in Downtown Pittsburgh, also grew up in Jalalpa. He entered the country without documentation in 1993, and has since received citizenship. When he was growing up in Jalalpa, Ruiz says, there were no jobs and no real careers available to its residents. “Some people worked in construction, many hawked products on the street,” says Ruiz. “My mom used to wash clothes by hand, my dad worked as a toll collector at the public market.”

When he was young, Ruiz would travel to the market early in the morning, waiting for the produce trucks to arrive. He would ask to sweep and clean the trucks, hoping to collect enough stray beans to bring back to the family for dinner.

These harsh conditions led many in the neighborhood to turn to drugs, either using or selling, says Ruiz. “When I was 16, what am I gonna do here? If I don’t leave, I am gonna start behaving like my peers,” he says.

Ruiz, whose brother still lives in Jalalpa, has visited every year since receiving his green card and says little has changed since he departed. He says the drug problems have only increased; the area still lacks economic growth; and no help is on the horizon.

“If you don’t work, don’t find a way to make some money, the government is not going to help you out,” says Ruiz.

Monica Ruiz, Horacio’s wife, sees similarities between Jalalpa and Pittsburgh. When the steel industry fully collapsed, in the 1980s, Pittsburgh experienced unemployment rates as high as 20 percent. Hundreds of thousands of people departed the region as a result.

“How bad was it when the steel industry left?” says Monica, a Cleveland native and social worker at Latino-advocacy group Casa San José. “Bad enough that Pittsburghers left as a response. That is what you do, you get up and go. You go to where there are more opportunities. How is Martín different? He is trying to do the best for his family, just like people did here.”

On Nov. 3, 2011, after Martín fulfilled his obligation to the Mexican army, he said goodbye to his family.

“Take care, good luck, and God bless you and your family,” Martín says his sister told him. “The one who has helped us the most is now leaving.”

Martín’s account of his journey from Mexico City to Pittsburgh is taken from more than 50 pages of handwritten letters to CP. (Casa San José volunteer Carmen Urrutia translated the letters Martín wrote from prison. Urrutia has not been involved in Martín’s advocacy, nor has she met Martín.)

After leaving Mexico City, he caught a flight to Nogales, Mexico, with just a backpack, one set of clothes, and 800 pesos (about $40) in his pockets

The bordertown sits directly next to Nogales, Ariz., in the heart of the Sonoran Desert, known for its giant saguaro cacti. At the airport, he was questioned by police about where he was going, and they took him into a room to interrogate him. Some were laughing, and saying, “This one is going to the other side.”

Eventually, the police made it clear they wanted a bribe, so Martín gave them 500 pesos and they let him go. After a 250-peso cab ride, Martín arrived at the Pancho Villa Hotel, where he would meet his coyote, Doña Lupe de la Poblana.

But first, Martín needed more money to stay in the hotel and to pay the coyote’s fees. He was able to receive wired funds from his mother in Pittsburgh, but was still terrified he was going to be caught, fearing his Mexico City accent would expose him to local authorities.

In a church not far from the hotel, Martín prayed: “Please God, take away my anguish.”

The next morning at 9:30 a.m., he was awoken by Lupe’s aides; he would be crossing soon. A man nicknamed Cholo escorted Martín to a section of the wall, where he claimed the camera wasn’t functioning. Martín was worried.

“If you listen to me, everything is going to be all right,” Cholo told him.

Martín was boosted over the 8-foot wall and within seven seconds, he was spotted by a plane. Soon after, Martín was apprehended, cuffed and made to sign documents in English he couldn’t understand. (These were most likely papers pleading guilty to crossing the border without valid documentation. According to stats from Syracuse University, misdemeanor illegal-entry cases make up more than 60 percent of all immigration charges and more than 95 percent of those are prosecuted at the border.)

He spent the night in a cold cell and was released back to Mexico the next day.

Over the next several weeks, Martín spent days and nights with 15 people crammed into a room at the Pancho Villa, and even participated in an attempt to cross again, where they spent 10 hours hiking in the desert, two days waiting near the border with little food and water only to return to the Pancho Villa when the attempt was called off.

His desperation was increasing because his son, Alex, had been born at the Santa Clara Valley Health Center in San Jose that month, and he knew he should be with his family. He cried many nights because he had missed the moment.

Eventually, the coyote Lupe decided another strategy would get Martín across. He was taken to a hair salon, where his hair and eyebrows were trimmed and dyed to make him resemble a “mica” Lupe had given him. “Micas” are fake credentials, usually counterfeit green cards.

On Dec. 6, 2011, Martín was to be driven from Nogales to Tucson, Ariz., by a driver with proper U.S. documentation. However, during the trip, the driver was sweating and visibly nervous. (Aiding and harboring undocumented immigrants is a federal felony.) Martín exited the car before they reached the border crossing because he was afraid the driver’s anxious appearance would tip authorities off. He walked to the border crossing by himself. When asked by border patrol why he was entering the U.S., Martín told the officer he was going to Arizona to purchase antifreeze. The officer looked at Martín’s “mica,” didn’t buy its validity or his antifreeze story, and he was detained again in a small, cold cell, shivering all night.

The next day, he was taken into court and the immigration judge told him that he should not come back this way, because he would go to jail.

Due to the large volume of immigrants getting caught attempting to cross without documentation (even though numbers have shrunk since peaking, in 2011), these court proceedings near the border are typically a hasty process. (Carlos Garcia, of the Puente Human Rights Movement, a Phoenix-based migrant-justice group, says it’s normal to have 60 to 100 cases prosecuted in one day.)

After pleading guilty to illegal entry (a misdemeanor), he was taken to a nearby prison and forced to remove all his clothing, so officers could check whether he was concealing any drugs. Martín was then driven by bus for five hours and released in Mexicali, Mexico, right across the border from California.

Lupe wired him money so he could return to Nogales, and a day later he arrived back at the Pancho Villa Hotel. Upon his return, Martín says the hotel clerk told him, “You have really bad luck.”

Some might say that bad luck also contributed to Martín being detained by ICE here in Pittsburgh. But Guillermo Perez, president of Pittsburgh’s chapter of the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement (LCLAA), which has been advocating on behalf of Martín since he was detained by ICE, thinks the reasons were more intentional.

In March, Martín was pulled over in Mount Lebanon for a traffic violation. When CP visited Martín in the Youngstown prison, he said officers pulled him over for failing to stop at a pedestrian crosswalk. Martín said he didn’t see any pedestrians waiting to cross the street.

Perez believes Martín might have been pulled over for what he calls “driving while Latino.”

“We don’t know why exactly Martín was pulled over,” says Antonia Domingo, also of LCLAA. “But we assume it may have something to do with the color of his skin.”

Domingo says rumors are circulating in the Latino community that these types of traffic stops are increasing in Pennsylvania, and says there has to be some link, even if currently inexplicable, between undocumented immigrants getting pulled over for minor traffic offenses and ICE detaining them shortly after.

According to court documents, at least two other undocumented Latino immigrants in Southwestern Pennsylvania were also picked up in the last few years and charged with immigration felonies, after local police cited them for minor offenses. Walter Melgar, an El Salvador native living in Altoona, pled guilty to a false identification charge on Dec. 28, 2015; he was identified by ICE the next day. Jose Hernandez-Segura, also a native Salvadoran, was cited for disorderly conduct and driving without a license on April 19, 2014, by Leetsdale Police; he was charged with felony re-entry two months later. Both men had no prior criminal record.

Domingo says this is unjust because many undocumented immigrants in the Pittsburgh area work in residential construction, and they need cars to drive from worksite to worksite. Pennsylvania doesn’t allow undocumented immigrants to receive driver’s licenses. (Twelve states in the U.S., including nearby Maryland and Delaware, allow undocumented immigrants to receive some form of driver’s license.)

In Martín’s case, the racial-profiling theory might carry some weight. Court magistrate documents show that Martín wasn’t cited for failing to yield to pedestrians. Mount Lebanon Police cited him only for driving without a valid license, without valid registration and without valid insurance. But it’s highly unlikely that Mount Lebanon authorities would have been able to determine these infractions before stopping Martín and requesting documentation. The car Martín was driving has a Michigan license plate, and while the registration sticker did expire in October 2015, the year was printed in 8-point font and can be read easily only from about two feet away, while the car is stationary.

Lt. Duane Fisher, of the Mount Lebanon Police, left a voicemail in July with CP saying the township’s general policy is to make contact with ICE if police “find someone who is unlicensed” and to see whether ICE has “any reason to see if [the suspect] is wanted.” Fisher says that from there, Mount Lebanon police don’t follow up on the case, and that it becomes ICE’s call.

Upon further questioning, Fisher wrote that the Mount Lebanon “Police Department empathizes with Martín about his potential deportation. We do not enforce traffic laws with the intention of separating a person from family or country.” Fisher added that it’s not uncommon for officers to initiate traffic stops and then find other violations, and that it would be difficult for officers to determine “with any certainty items such as race or sex” before pulling over the vehicle. He wrote of Martín’s case:

“It was discovered that Martín had numerous characteristics that matched a wanted person. Only through the efforts of the officer at the scene was it ultimately determined that Martín was not the subject of the warrant. Federal and state agencies monitor all queries we make in regards to licenses and registrations. While we made no additional efforts in regard to Martín, it would not be unusual for another such agency to investigate when an inquiry so closely matches the description of a wanted person.”

However, court documents released Sept. 26 say that a Mount Lebanon Police officer “sent an inquiry” about Martín and his date of birth to ICE. This inquiry led to ICE contacting Mount Lebanon police and eventually detaining Martín on May 2 to obtain his finger prints and confirm his identity.

Pittsburgh has a policy to not initiate contact with ICE, but will cooperate if contacted, according to a 2014 city order. However, the city’s policy doesn’t apply in Allegheny County’s 129 other municipalities, and it is unclear how many of them have followed in Pittsburgh’s footsteps.

"The love for someone’s family is the most important thing.”

tweet this

Back in Nogales, Mexico, in late 2011, Martín started to wash cars to pay for food and board at the Pancho Villa. Other than another attempt to cross the border, in which a group of people waited in the Mexican side of the desert for two days only to be called back to the Pancho Villa, Martín was mostly forced to wait.

About two months later, on Feb. 7, 2012, he attempted another crossing by walking through the desert with a group; but that attempt ended in capture. He proceeded quickly through immigration court again (court documents show he was charged with felony illegal re-entry, but took a plea deal, and was charged with misdemeanor illegal entry). Martín served about 30 days in a jail in Phoenix and then 30 days in a private prison in Las Vegas. (The facility was run by the same company, Corrections Corporation of America, which currently houses him in Youngstown.)

After finishing his sentence, Martín was shipped by bus to Tijuana and released. He says some of the other immigrants celebrated being released by partying with drugs and alcohol. Martín didn’t participate; he knew his journey was far from over.

By now, Martín’s mother and Lupe the coyote knew a different entrance strategy was necessary. With money wired from his mother, Martín received a temporary Mexican ID (his previous ID had been confiscated when he was caught by border patrol the second time) and caught a flight to Nuevo Laredo, which is directly across the Rio Grande from Laredo, Texas.

Shortly after arriving in Nuevo Laredo, he crossed the café-au-lait colored waters of the Rio Grande at Rio Bravo, a tiny town just south of Laredo, with another coyote and another group of immigrants. But Martín could not swim, so he had to blow up an inner tube. He stripped and carried his clothes over his head to keep them from getting wet while he floated across the river.

After reaching the bank, he walked 30 minutes through rocks, thorns and mud, but made it through. Two others in his group abandoned the trek and returned to Mexico.

The group that did make it found a dilapidated house to hole up in nearby. It was in bad shape; the floors were covered in dirt and there was no toilet paper (they used plastic bags) or hot water. The migrants slept on the floor, where cockroaches crawled across Martín as he slept.

Martín had no idea how he would travel safely to his cousin’s home in Austin, some 250 miles away. To make it through the few nights at the house, he says he thought of being reunited with his daughters and meeting his newborn son. He knew that if he didn’t make it, they were going to suffer.

“Who would take better care of them than their mother and father, together? That is what kept me going,” he wrote to CP.

Martín remembered the lessons taught to him by the army. He was taught that anyone who doesn’t finish a mission is a coward. He will teach his kids that someday, he thought, because their father should be a role model.

He was also reminded of his parents. “They did the best they could to provide,” wrote Martín. “But because of their lack of education, they did not reach the goals that they wanted. They ingrained the love of family in me forever. The love for someone’s family is the most important thing.”

While laying in the cockroach-infested house, with the sun setting and the temperature dropping quickly, he thought about how his mother always told him never to leave his kids behind. With that sentiment fresh in his mind, and with the huge amount of love he has for his kids, he vowed that May night that he would never leave them behind and let them suffer. “This is why I never gave up.”

So far more than 30 notarized letters have been written by pastors, professors at the University of Pittsburgh, public-school teachers and Martín’s employer in support of him. Pittsburghers have started to donate time and money to his cause, and his advocates have gathered around 1,000 signatures so far, asking Western Pennsylvania District U.S. Attorney David Hickton to drop his charge.

“Hickton, escucha, estamos en la lucha [Hickton, hear us, we are in this fight],” the marchers shouted on Beechview’s Wenzell Avenue.

Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto has also chipped in. Peduto sent a representative to the rally to speak in support of Martín, and has helped Martín find a pro-bono immigration lawyer to take up his deportation case, which will come after the outcome of his federal case.

“Pittsburgh is committed to being a welcoming city for immigrant families while also protecting public safety for all,” wrote Peduto in an email to CP. “We have a strong interest in working with federal partners to uphold these commitments. We want to create opportunities for new Pittsburghers, not deny them.”

The mayor also brokered meetings so that Martín’s family could come face to face with federal politicians, like U.S. Congressman Mike Doyle (D-Forest Hills).

Doyle told CP in September that Martín has been a “model citizen.”

“By all standings, this is someone who should have a path to citizenship,” said Doyle.

Doyle’s staff has also spoken with U.S. Attorney Hickton to see if Martín’s charges could be dropped, but is now looking into the circumstances of when Martín was pulled over, to determine whether racial profiling played a role in the stop. Martín’s criminal lawyer, Sally Frick, who is defending him for drastically reduced fees, is also aggressively pursuing this avenue for Martín’s defense.

But while a community of activists is fighting tooth-and-nail for Martín, a more powerful force is attacking undocumented immigrants across the state and the nation.

Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, now notoriously, kicked off his campaign by calling undocumented Mexican immigrants “rapists.” U.S. Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.) is currently running ads for his re-election campaign claiming that Democrats want to give “welfare towards illegals.” And several Pennsylvania state legislators, like Butler County Rep. Daryl Metcalfe (R-Cranberry), have consistently introduced legislation aimed at attacking immigrants, including English-only rules, denial of birthright citizenship, and a recent bill requiring U.S. identification to receive public benefits.

“We are here to send a very public message to Congress,” said Metcalfe in a 2011 New York Times article. “We want to bring an end to the illegal alien invasion that is having such a negative impact on our states.”

Carter, of the Pennsylvania Immigration and Citizen Coalition, disagrees with that premise.

“Every piece of anti-immigrant legislation that our state lawmakers introduce doesn’t solve any problems, it just demonizes a group of immigrants,” says Carter. “There has never been a case of an undocumented immigrant illegally accessing welfare services in the state.”

In fact, according to data compiled by the Migration Policy Institute, the majority of Pennsylvania’s undocumented immigrants speak English well or fluently, their employment rates are actually a bit higher than rates of U.S.-born Pennsylvanians, and more than 70 percent have lived in the country for five years.

Carter says the attacks from some GOP politicians in the Keystone State are misguided, because Pennsylvania is home to such a small percentage of those who have arrived without documentation. Pennsylvania, the sixth most populous state, has the 16th most undocumented immigrants. According to the Migration Policy Institute, Pennsylvania had around 136,000 undocumented immigrants, or 1 percent of the state’s population. In fact, of the 25 states with the most undocumented immigrants, only Ohio and Michigan have smaller percentages of undocumented immigrants than does Pennsylvania, and only by fractions of a percent.

Still, Carter says anti-immigrant bills pop up in Pennsylvania’s legislature every year and pass through committee, with Republicans supporting them and Democrats opposing. But when these bills are fully discussed, they get voted down because lawmakers realize they are a waste of resources. “They never pass, they are just bad public policy,” Carter says.

After about a week in the run-down house in Southern Texas, the night came for Martín to travel through the final ring of checkpoints, some dozens of miles north on all highways exiting Laredo. Martín crammed into a truck with 12 other people and felt like “sardines in a can.”

After about 30 minutes of driving, their coyote, “Flaco,” told them to exit the car. They entered the desert on foot. The group walked all night, crouching among thorny bushes and crawling on rocks to avoid being spotted by passing cars. Eventually they made it to a stable filled with cows where they would spend the day hiding out. They had run out of water, so many drank from a trough filled with muddy water.

One evening, Martín and three others packed into the truck again and make a dash past the border patrol in Hebbronville, Texas. On the road, lights appeared behind the truck. Flaco told the group to make a run for it.

Two of them, along with Flaco, jumped out of the truck, and sprinted into the scrub. Martín says he prayed to God, and asked for protection before taking the wheel, fearing the truck would crash into a young man who exited the truck.

Martín stopped the car and ran toward a fence near the border-patrol station. He jumped the fence, but cut his hand on barbed wire and injured his ankle on the descent. He was running in the dark, his ankle throbbing in pain.

Martín tripped and fell into a bush full of thorns, giving border-patrol agents enough time to catch him again.

“Why are you running?” the agent asked Martín in Spanish. “I don’t like when people make me run, piche pendejo [fucking idiot].”

Once in custody, Martín was harassed by agents who believed he was the coyote. “You speak English and you live in Atlanta,” an agent screamed at him in Spanish. “If you are lying it is going to be a bad road from here.”

“I am not a coyote,” Martín pleaded in Spanish. “I have never even been to Atlanta.”

Eventually, the officers realized their mistake and shipped Martín off to a nearby detention center with the other immigrants Martín attempted to cross with.

Martín asked the girl and woman who jumped out of the car if they would try again. The woman said no: “It was too hard.”

Replied Martín, “If I get caught again, I might not try, too.”

"I don't see anything positive for anyone coming out of this. It is tearing apart a family."

tweet this

When Martín was detained by ICE this May in Pittsburgh, it was his fifth time in immigration custody. But this time was different; this time he had finally established a new life in a new country. His kids were attending Pittsburgh schools, he had steady work, and his family was active in two churches and Latino-advocacy groups.

This time between detentions is important for Martín’s advocates; they say it’s crucial in showing he is not a priority for deportation.

“He does not fit the priority, he should never have been picked up in the first place,” says Perez of LCLAA. “This prosecution makes no sense.”

In fact, it’s questionable whether Martín even falls under the federal guidelines for priority immigration enforcement. A 2014 memo by Department of Homeland Security secretary Jeh Johnson lists the government’s current priorities for deporting undocumented immigrants. They include detaining non-citizens who are suspected of terrorism plots, involved in gangs, convicted in “aggravated felonies,” and other less serious offenses. Only two descriptions apply to Martín. Martín was apprehended at the border, which is a “Priority 1” qualification, and so he was deported the four times he was caught there. But his latest apprehension was here in Pittsburgh, more than 100 miles from any international border. That would place him under the “Priority 2” description. But this description applies only to undocumented immigrants who cannot establish continuous physical presence in the U.S. since the start of 2014. Martín has an established presence in the states since mid-2012.

According to data from Syracuse University’s Transaction Records Access Clearinghouse, ICE field officers have largely ignored Johnson’s issued priorities. During the first two months of 2016, more than half of ICE detainees nationwide had no criminal record, which was actually slightly higher than before the secretary’s 2014 memo outlining the priorities.

Perez says that Martín’s charges should be dropped for this reason alone and that ICE should be practicing “prosecutorial discretion.” LCLAA drafted a letter to Pennsylvania ICE Field Office Director Thomas Decker requesting he support their cause in getting Martín’s case dropped. The letter claims Martín was not only the possible victim of racial profiling by local police, but that he has become a “community asset” and his deportation would cause his family “extreme hardship.” (Martín was the sole breadwinner for the family before being detained.)

There have been very few cases where an undocumented immigrant has had his or her felony illegal re-entry charges dropped, according to a CP record search. This May, Oregon District U.S. Attorney Billy Williams dropped charges against Francisco Aguirre-Velasquez, who had been an advocate for immigrant-rights for years. Aguirre-Velasquez was considered an aggravated felon (one of the qualifications for being considered an ICE priority), but Assistant U.S. Attorney Greg Nyhus wrote on his dismissal form that the case was being dropped “in the interest of justice.” (ICE did not respond to requests for comment for this story.)

Perez believes the same reasoning could be applied to Martín.

“I am not happy about attacking [U.S. Attorney] David Hickton,” says Perez. “He appears to be a very good person. He is just not showing that towards our community. I don’t see anything positive for anyone coming out of this. It is tearing apart a family. Creating fear and sending a bad message to the Latino community.”

In a needs-assessment for area Latinos conducted by Allegheny County, 32 percent of respondents said family reunification sat atop their list of priorities, the largest percentage of any answer given. Perez believes Martín’s prosecution is a step backward for the region’s growing acceptanced of Latinos.

But Perez adds that federal prosecutors are determined to prosecute Martín anyway. According to a motion filed in Martín’s federal case, U.S. attorneys are aware of Martín’s advocates and their push to show his value to the community.

“The Government anticipates Esquivel-Hernandez may attempt to introduce non-relevant evidence during his trial. In particular, the Government expects Esquivel-Hernandez to introduce specific acts as evidence of his behavior and general disposition as a good person,” wrote Assistant U.S. Attorney Paul Hull. “[E]vidence, such as testimony of Esquivel-Hernandez’s involvement with his family in the United States, and his interaction and leadership in his community, should be prohibited.”

U.S. Attorney David Hickton refused to comment for this story.

After four days in a south Texas detention center, Martín was again made to sign papers he couldn’t understand in English, and was then deported to Matamoros, Mexico, more than 200 miles away, across the border from Brownsville, Texas.

He called his cousin in Austin, who wired him money and told him to take a bus to Reynosa, a border town 50 miles west of Matamoros. Martín says he spent another month in this town, walking around the central square and following the news.

He was nervous there, because the area has a bad reputation for violence and a large presence of drug cartels. He saw a news story one day about two dead bodies being discovered without IDs and worried he could become one of them.

“It was more of the love I have for my wife and kids, that it kept me from being scared,” Martín wrote.

His cousin eventually arranged for a coyote, who took Martín to his house and confiscated his cell phone. After about a week there, it was time for another attempt to cross; it would be Martín’s last.

This time, Martín joined a group that included mostly Chinese immigrants. They walked along the Rio Grande for hours as Martín was pestered by mosquitoes and ants.

At 9 a.m. the next day, the group was divided in two, and crossed in small boats, undetected. A five-minute walk later, Martín hopped over a wall. From there he journeyed along the banks of the river for days, until finally reaching a car that would transport him to safety. Martín crammed into the car with the group and they made it past another border patrol station 75 miles north, also undetected. His luck was finally turning.

Martín eventually made it to his cousin’s place in Austin, and he called his wife, Alma. “Be calm Alma, I am safe,” his wife recalls him saying. “Everything is going to be all right. I know now it is going to be okay.”

Martín found work in Austin. After he earned enough cash, his cousin found him a ride with someone from Dallas for $500. Martín rode with the man for two days until finally arriving in Pittsburgh, where he was reunited with his mother. He found another job so he could purchase plane tickets for Alma and the kids, who had been staying in Northern California.

Alma, Luz, Samantha and baby Alex flew to Pittsburgh on a red-eye. Martín was supposed to pick them up at the airport that morning, but he recalls his mother made him go to work, so she picked them up. When Martín returned to his mother’s home in Uptown at 7 p.m., it was dark, and light snow was falling on the street. Martín forgot his keys that day and banged on the door.

Alma and the kids rushed to open the door and the family embraced for 10 minutes. None of them could stop crying. He wrote to CP that it was the happiest day of his life.

“Please forgive me for all the time that we weren’t together,” Martín said.

Martín and Alma vowed from that moment never to be separated again.

On a Saturday in August, Martín finally got the chance to see his children again after being imprisoned for months. CP joined Alma, Samatha, Luz and Alex on a trip to the Youngstown prison where he was being held. After an hour-long car ride filled with whining from Alex, conversations with Samantha about her favorite Cartoon Network show, and Luz expressing her hope to share an afternoon with her dad at Kennywood (all in English), the family sat in a sterile prison waiting room for 20 minutes. (Alma didn’t get to see Martín; she was dropped at a nearby McDonald’s for fear the CCA staff might identify her and contact ICE.)

After taking off their shoes and walking through metal detectors, the kids entered the room and saw Martín’s smiling face through the glass window of the last stall farthest from the door. Samantha, Luz, and Alex ran to him, and Martín broke down instantly. He cried, and 9-year-old Luz picked up the phone first. “No llores, papá, no llores [Don’t cry, dad, don’t cry],” she said. Martín put his hand up to the double-panned glass and Alex placed his hand on the other side, bringing a smile to Martín’s face.

Luz sang him a song she discovered on a Spanish TV show to comfort him, “Mariposa, mariposa …” The room was mostly silent otherwise. None of the inmate’s voices penetrated the walls and windows. Occasional loud smacks emanated on the tile as Alex hopped from his chair, slightly interrupting the visitors speaking to prisoners through their black handsets.

After 15 minutes or so, the children settled into their routine with their father. Luz explained to him the plot of the animated film Zootopia, and Alex ran around playing with a plastic dinosaur. Martín, now with buzzcut black hair, told Samantha that she must be strong and take care of her siblings while he is gone.

They all played their favorite game, “rock, paper, scissors,” which Martín taught to each of his children. As the hour came to a close, Martín gave his family a thumbs-up and smile as his kids waved goodbye.

The gesture was eerily familiar. The day before he was detained, Martín could be seen giving thumbs-ups throughout an immigrant-rights march from Beechview to Brookline, spreading his positivity about his community to the Pittsburghers he met.

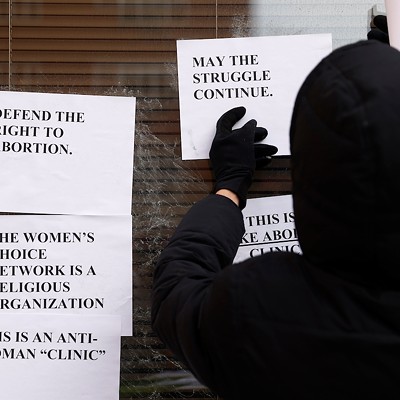

During the Sept. 25 rally, hundreds retraced the march Martín took on May 1, the day before he was detained. Casa San José, LCLAA, the Thomas Merton Center, college students and others shouted “Bring Martín Home!” as neighbors watched from porches.

Martín is the first undocumented immigrant facing deportation in the Pittsburgh area to gather such wide-spread community support. At the rally, Alma addressed the crowd, hopeful the push to save Martín can broadly influence immigrant rights in Western Pennsylvania.“Our campaign is not going to stop supporting Martín and our community,” Alma said in Spanish. “Today it is for Martín and my family, but tomorrow it could be for any other family. We can’t have fear when injustice occurs; we need to get our voices out for our children and our community.

“Damas y caballeros, hemos abierto la puerta para luchar por los derechos de los inmigrantes,” she said. Ladies and gentlemen, we have opened the door to fight for immigrants’ rights.