If elections were contests of ideas, Pittsburgh City Councilor Bill Peduto might already have won the mayoral primary.

In January, Peduto was the odd man out in a three-man field that included Mayor Luke Ravenstahl and City Controller Michael Lamb. Only Peduto supported waiving a city-residency requirement for police. Only Peduto was unwavering in seeking to keep the city operating under state financial oversight. Only Peduto supported a city ordinance requiring gun owners to report the loss or theft of firearms, a measure Lamb and Ravenstahl called "unenforceable."

But Lamb and Ravenstahl have dropped out of the race, replaced by former state Auditor General Jack Wagner and two other challengers. And for all the negative ads and debates that have ensued since then, Peduto and Wagner agree on all three of those issues. On these topics, what was a minority position six months ago will likely be administration policy next year. And Wagner too embraces bike-friendly policies and green infrastructure, even if his grasp isn't quite as tight as Peduto's.

But Peduto has spent years fighting for those issues, and has scars to prove it. He's been attacked by rivals on council, and by Ravenstahl himself, who's using a nearly $1 million campaign war chest to air ads attacking him. Beset by these foes, Peduto is attacking Wagner for his friends.

"There is a group that is supporting Jack, who represents the leadership that Pittsburgh has had for awhile," says Peduto. "And it's concerning to them that a new group is coming to power."

"Council today is a dysfunctional council," counters Wagner. "Bill is part of the problem."

Recent polling suggests the race is too close to call. When the candidates debate, it almost sounds like we're already living in Bill Peduto's Pittsburgh. But there's no guarantee he'll be its mayor.

For one thing, he's got credible opposition.

A.J. Richardson is running the kind of long-shot campaign that may actually have benefited from the added visibility of a DUI arrest. But state Rep. Jake Wheatley, who represents the Hill District and adjoining areas, is touting a single-minded focus on eradicating poverty — an issue that would likely get little attention from the candidates otherwise [see chart, "Running Amok"]. By focusing on industry-specific job training in schools and other education initiatives, Wheatley says, Pittsburgh will be "a lot more attractive to people who want to relocate here."

"When we talk about eradicating poverty, it's about lifting everyone up," Wheatley adds. And he's voicing the battle-cry of every underdog: "Let the ‘can he win?' question go to the wayside." If you asked that question when Obama first ran, he wouldn't be the [Democratic] nominee."

But polls suggest Peduto's biggest rival is Wagner, for whom this mayoral campaign has a familiar theme. Wagner first won a city-council seat, in 1984, by decrying government dysfunction, campaigning on the theme "Stop the Circus."

Wagner himself wasn't immune from the chaos. A battle over the council presidency with then-councilor Jim Ferlo, for example, ended up in court. But by 1990, newspapers were reporting a new era of "peace and courtesy" on council.

"There was a far better working relationship on council after I got on," Wagner says. And Wagner says he grew as a politician himself.

As a city councilor, for example, he'd opposed legislation adding gays and lesbians to the city's anti-discrimination ordinance. But as a state senator a decade later, he sponsored or co-sponsored numerous LGBT-friendly bills — and in the 1990s, supporting LGBT causes wasn't necessarily a gimme for a Western Pennsylvania politician.

"Every issue I have voted on in the past has not always been the right vote," he says of his initial opposition.

Wagner's supporters tout his own independence. Wagner is "going to be his own man," predicted Ferlo, Wagner's former council foe, when he formally endorsed Wagner March 27. (The two men became compatriots in the state Senate.) Ferlo noted that as the auditor general, Wagner was "an equal-opportunity critic" of Democratic Gov. Ed Rendell and his Republican successor, Tom Corbett.

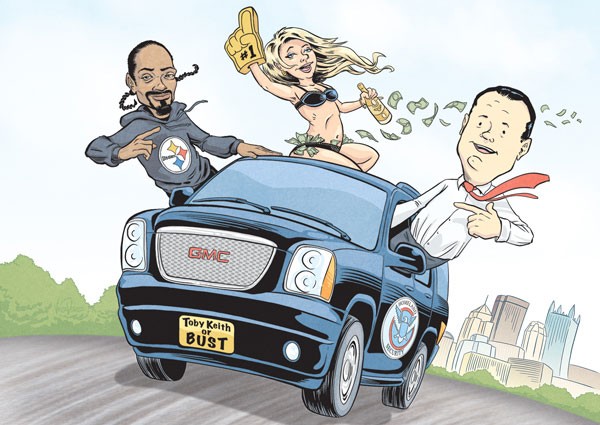

But Ferlo was originally a Ravenstahl backer, and he's not alone. Other former Ravenstahl loyalists now backing Wagner include city councilors Ricky Burgess and Darlene Harris, as well as the firefighters and some building-trades unions.

"Their coalition is built off the [people] that have been running the city for years," says Peduto. "For them to say they are not part of the Ravenstahl machine ... is just false."

Wagner may prune city government more than some critics expect ... and more than some allies hope. If he's elected, Wagner predicts, "I see the majority of people in the mayor's office being new people. There is going to be a new administration." For example, he says, "I would fully expect [mayoral chief of staff] Yarone Zober to move on."

But so far in this campaign, Wagner hasn't yet been forced to choose between his allies and his agenda. And on issues where a collision seems possible, his stance can be difficult to pin down.

In mid-April, for example, invitations surfaced for a $1,000-a-plate Wagner fundraising luncheon, co-hosted by "members of the Marcellus Shale Community." Did such support mean that Wagner would favor lifting a city ordinance — favored by Peduto — that bans drilling within city limits? "I know of no interest ... in introducing such a bill," he said. "[N]o one wants to drill in the city," he added, and "I am an advocate of supporting that." So what would he advocate if someone did want to drill? It's not clear.

Team Wagner has sought to portray Peduto as "divisive," offering Wagner as a potential bridge-builder. "I think we need to emerge with a mayor that has some consensus," is how Ferlo put it. But being a consensus candidate is a lot easier when you can adopt a platform, rather than having to fight for it.

For Peduto, the struggle has lasted the better part of a decade. In 2007, he ran a brief, joyless campaign against a then-popular Ravenstahl, then dropped out in mid-March. He did so, he told City Paper at the time, because his only hope was to run a savage, negative race — and even then he was likely to lose. That setback, he said "probably would have ... destroyed a reform movement" — one he'd worked "over a dozen years to build."

This year, it's Ravenstahl who dropped out — and Peduto hasn't shied away from going negative. (Two of his TV ads have blasted Wagner for voting in Harrisburg to raise his own pay, and for supporting Republican budgetary rhetoric.) More importantly, he says, that "reform movement" is less vulnerable today.

When his campaign held an April 25 show of support this year, more than three dozen elected officials and other leaders attended, including local and state leaders from outside Peduto's traditional East End base. Some had been elected with help from Peduto's own political team, part of an ongoing effort to create what Peduto calls a "New Coalition."

And for a time, at least, Peduto also had legislative momentum on his side. Between 2010 and 2011, when Peduto was part of a council majority, he helped shepherd through a variety of reforms, including campaign-finance limits, the lost-and-stolen gun bill and a "prevailing wage" measure setting a higher-than-minimum-wage floor for workers at grocery stores and other projects receiving tax subsidies.

Peduto remains the policy-wonk's dream candidate. His campaign website features scores of policy proposals. Some, like a proposed financial-literacy program, could be done outside city government. (Though Peduto says all the ideas "really need a leader that is part of government [and] can see the potential" to be sustainable.) But for supporters, when Peduto recommends using city resources to convert underused building space into "Innovation Incubators," the main point is the idea's specificity. Go to Wagner's site for his thoughts on job creation, by contrast, and you'll see a vague promise to "partner with local business leaders to identify growth opportunities."

Peduto says such a disparity reflects the fact that he has "more hands-on experience of the transition from old Pittsburgh to new Pittsburgh than any other candidate." Meanwhile, "Jack's been away for 20 years. The city has changed."

But not as fast as Peduto would like. On city council itself, a lasting coalition has been more elusive: Harris, who headed up Peduto's bloc as council president between 2010 and 2011, parted ways with him the following year. In endorsing Wagner, she denounced Peduto for holding "petty grudges."

And many of his legislative initiatives have languished, casualties of Ravenstahl's hostility or indifference. At least one reform, the campaign-finance reform, has been found wanting. During a court battle between Wagner and Peduto over the rules, Judge Joseph James voided contribution limits for this year's mayor race on a technicality, and expressed hope that the rules could be amended "between now and the next election."

At the same time, Ravenstahl has tapped his now-idle campaign treasury to attack Peduto in TV ads, which claim Peduto only cares about his own district. Many of the attacks — like the complaint that Peduto was the lone vote against a senior housing project in Homewood — echo criticisms lodged at Peduto by Burgess, a frequent foe. Wagner, meanwhile, is in the enviable position of benefiting from the ads while denouncing Ravenstahl and Peduto for the lack of civility: Both, he says, should "grow up."

Peduto acknowledges some frosty relations on council but says, "I've never let it get in the way of doing business." But he makes no apologies for being a strident foe of business-as-usual.

If elected, for example, his housecleaning will include asking mayoral appointees to city boards, authorities and commissions to resign. Unlike Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald, a Peduto ally who has previously required appointees to sign undated letters of resignation he could use at any time, Peduto says his appointees can vote without fear of removal. "I'm not telling them to vote a certain way," he says. But "[w]ithout bringing new people in, you're not accomplishing the goals you set." (Wagner, meanwhile, says he'd allow appointees to serve out their terms.)

"I've been leading a new coalition in this city for years," Peduto says. "We're ready for our turn."

If voters do decide Peduto is too much a part of "dysfunctional" government, the person who might best sympathize is ... Jack Wagner. In the city's 1993 mayoral race, Wagner was trounced nearly 3-to-1 by then-state Rep. Tom Murphy. As returns came in, his press secretary lamented to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, "[T]here was such a demand for change. [Murphy] was totally [out of] city government and Jack was in city council."

This time, that dynamic may help the former auditor general ... even if his own proposed changes are more modest.

Peduto champions a community-driven redevelopment and decision-making, empowering neighborhoods instead of political players. That approach, he's fond of saying, will "turn upside-down the top-down model of [legendary former Mayor] Davey Lawrence."

Wagner strikes a different note. Just after Peduto spoke to an audience at an April 29 forum in Brookline, Wagner said "I'm here tonight to ask for your support — because Pittsburgh does not need to be turned upside down."

Wagner promises changes too, like an enhanced role for city planners in development. But while Peduto focuses on how he'll make residents part of the conversation, Wagner's message primarily emphasizes how officials speak to each other.

After the contentiousness of the Ravenstahl years, it's not clear which vision voters will choose. This election may be decided by how much change Pittsburgh really wants. And how easy we expect it to be.