As a chemical engineer, Sharene Shealey understands the importance of a first-rate science education. But Shealey, who became a Pittsburgh Public Schools board member last year, never realized how few students may be getting one.

Sitting in an empty meeting room inside the district's Oakland headquarters on April 13, Shealey touched her forehead in dismay as she sifted through the district's poor test scores from last year's state assessments. "Wow," said Shealey, an air-quality specialist for RRI Energy. "I'm taken aback."

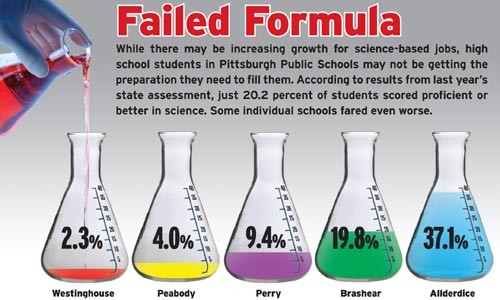

According to results from the 2009 Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA), just 20 percent of the city district's 11th-grade students scored "proficient" -- a designation reflecting satisfactory performance -- or "advanced" in science. That's 30 percentage points less than what those students averaged in reading; 23 points less than math; and 53 points less than writing.

In half of the city's high schools, fewer than one out of 10 students scored proficient or better. In Oliver, Peabody and Westinghouse -- the three worst-performing schools -- fewer than one out of 20 students were proficient.

Administrators caution that the numbers may not be as bad as they look. The PSSA, they contend, doesn't focus on the kind of science many district students are learning.

Still, Shealey says, "I'm shocked. In fact, I'm fearful for the future."

Science PSSA scores aren't very impressive outside the city, either: Only 40 percent of the state's 11th-grade students scored at the proficient or advanced level last year. (By contrast, 65 percent reached the same level in reading; 55 percent in math; and 82 percent in writing.)

"It's scary," says Carey Harris, executive director of A+ Schools, a local nonprofit organization that monitors Pittsburgh city schools. "[Scores] aren't good anywhere. Given the demand for STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering and Math] careers, it is concerning that we're not getting kids ready" for science jobs.

"These are the fields that are competitive in this global economy," agrees Leah Harris, a spokesperson for the state Department of Education. "That's what we need to prepare our students for."

According to local and state education officials, there are a few reasons why science PSSA scores lag behind other subject areas. One is simple: Science is a relative newcomer to the state assessment. Science and writing were added to the state exam just two years ago. Reading and math, meanwhile, have been tested by the PSSA for a decade.

As a result, Harris says, it may take a while before teachers are able to prepare students for the science exam. With time, she predicts, "[Scores] are going to get significantly better."

But some say there's another possible explanation for the low test scores in science: academic priority.

Reading and math PSSA scores, unlike science and writing, are used to determine whether districts meet federal Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) standards. Failing repeatedly to meet AYP standards can have serious consequences for districts, including mandatory changes in curriculum, as well as replacements of principals and other school staff.

And Pittsburgh schools have shown improvement in those areas: For the first time since the federal standard was created in 2001, the district achieved AYP, thanks mostly to strong scores by elementary students in reading and math.

But districts like Pittsburgh are more apt to focus more on reading and math, rather than science.

"Science technically doesn't count," says Michele Cheyne, a clinical instructor at the University of Pittsburgh's School of Education who specializes in science education. Even though poor performance in science is "an issue we need to take a look at," she says, "There aren't any sanctions if a district doesn't meet standards in science."

Harris notes that there is some justification for emphasizing math and reading: "If you don't have that foundation, a student's not going to be able to do science well," she explains. "But that shouldn't take away from the importance of science education."

While scores for high school students are the worst in the district, scores in middle school reveal problems as well. Only 31 percent of the district's eighth graders, for instance, scored at least "proficient" on the science exam. Two schools -- Weil, in the Hill District, and Manchester, on the North Side -- had 0 percent of their students hit that mark. ("Oh my God," Shealey remarked as she saw Weil's test results.)

"We have to do much better," says school-board member Bill Isler. "All students have to be literate not just in reading and writing, but also in math and science."

"The scores are weak," agrees Mark Roosevelt, superintendent of the Pittsburgh Public Schools. "[Students] haven't been taught the material they're tested in. That's the only conclusion you can draw."

District officials say they're working on changing that. According to Dr. Jerri Lippert, executive director of the district's Office of Curriculum, Instruction and Professional Development, the low scores largely stem from the fact that "[o]ur courses weren't aligned to state standards."

The science PSSA focuses heavily on biology, chemistry and physics. But in addition to those core subjects, students in Pittsburgh have also been able to take classes in a range of fields -- including environmental science, earth and space science, and tech science -- the test largely glosses over.

Over the past couple of years, however, Lippert says school officials have been working to ensure that the district's science curriculum in grades 6 through 12 focuses more on the core programs.

Otherwise, she says, "There would be gaping holes" in the curriculum.

One bright spot can be found in the district's elementary schools, where nearly 64 percent of fourth-grade students scored proficient or advanced on last year's science PSSA. School officials credit those scores to an elementary curriculum that is more closely aligned with state standards.

But at higher grade levels, where the curriculum is broader, the scores take a nosedive -- even within K-8 programs that are housed in the same building.

At Squirrel Hill's Colfax, for instance, 87 percent of the school's fourth-graders scored at least proficient on last year's state exam. By contrast, just 27 percent of the school's eighth-graders did.

"In one building, you go from 87 percent to 27 percent," says school-board member Shealey. "That's absurd."

Lippert hypothesizes that the district's middle- and high school students will improve as changes in the curriculum take shape, and teachers learn how to better prepare students for state exams.

Exactly how long will that take?

Says Lippert: "I wish I could predict that."