Death of a Salesman at Pittsburgh Public Theater

Zach Grenier literally grinds himself into the earth over the course of the play

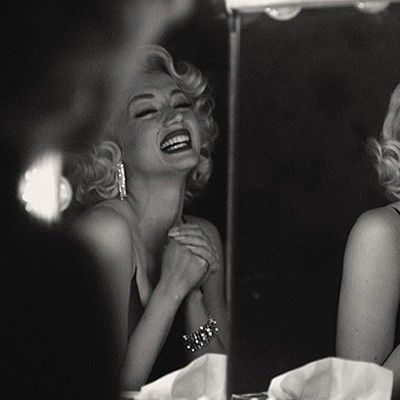

Kathleen McNenny and Zach Grenier in Death of a Salesman at Pittsburgh Public Theater

DEATH OF A SALESMAN

continues through May 21. Pittsburgh Public Theater, 621 Penn Ave., Downtown. $15.75-66. 412-316-1600 or ppt.org

We’re never really told what Willy Loman sells, but like any salesman, he’s really selling himself.

Portraying such an archetypal character in one of the American theater’s canonical works is itself a tough sales job, yet Zach Grenier succeeds in creating a vivid and original interpretation of this man whose fate is summed up by the title of Arthur Miller’s 1949 play, Death of a Salesman (presented by Pittsburgh Public Theater).

Although we live in an era that celebrates public outrage, and seems to justify personal grievances more when they can be anchored to larger social constructs, great dramas usually focus on the problems of the individual. As Susan Sontag observed 50 years ago in an essay on Miller, “The best modern plays are those devoted to raking up private, rather than public, hells.”

Grenier, an accomplished stage, film and TV actor, literally grinds himself into the earth over the course of the play, as if Willy’s growing smaller, or sinking into his own private hell.

His Willy is inebriated with failure, such that he is living more in reverie than in reality, like a man on an existential bender of despair and regret.

Director Mary B. Robinson helps the action skip around in time (reflecting the distorted temporality in Willy’s head), brilliantly intertwining decades-apart scenes like someone reliving memories from a photo album that’s been shaken all over the floor. She could give Heidegger lessons in phenomenology.

Willy’s wife Linda (played with dynamic restraint by Kathleen McNenny) picks up the pieces, and sees the bigger picture: “A small man can be just as exhausted as a great man.”

Sons Biff (Alex Mickiewicz) and Happy (Maxwell Eddy) amount to nothing more than living, empty dreams for Willy (both actors convey the feckless energy these roles demand), while his dead brother Ben (Tuck Milligan) persists as a powerful, consoling ghost.

James Noone’s set is as pragmatic as it is simple — well-suited to furnishing a dreamscape — and Tilly Grimes’ costumes evoke the feel of that famous cover from the Viking Press edition we all read in high school.

This production certainly reminds us how personal hell can be.

Portraying such an archetypal character in one of the American theater’s canonical works is itself a tough sales job, yet Zach Grenier succeeds in creating a vivid and original interpretation of this man whose fate is summed up by the title of Arthur Miller’s 1949 play, Death of a Salesman (presented by Pittsburgh Public Theater).

Although we live in an era that celebrates public outrage, and seems to justify personal grievances more when they can be anchored to larger social constructs, great dramas usually focus on the problems of the individual. As Susan Sontag observed 50 years ago in an essay on Miller, “The best modern plays are those devoted to raking up private, rather than public, hells.”

Grenier, an accomplished stage, film and TV actor, literally grinds himself into the earth over the course of the play, as if Willy’s growing smaller, or sinking into his own private hell.

His Willy is inebriated with failure, such that he is living more in reverie than in reality, like a man on an existential bender of despair and regret.

Director Mary B. Robinson helps the action skip around in time (reflecting the distorted temporality in Willy’s head), brilliantly intertwining decades-apart scenes like someone reliving memories from a photo album that’s been shaken all over the floor. She could give Heidegger lessons in phenomenology.

Willy’s wife Linda (played with dynamic restraint by Kathleen McNenny) picks up the pieces, and sees the bigger picture: “A small man can be just as exhausted as a great man.”

Sons Biff (Alex Mickiewicz) and Happy (Maxwell Eddy) amount to nothing more than living, empty dreams for Willy (both actors convey the feckless energy these roles demand), while his dead brother Ben (Tuck Milligan) persists as a powerful, consoling ghost.

James Noone’s set is as pragmatic as it is simple — well-suited to furnishing a dreamscape — and Tilly Grimes’ costumes evoke the feel of that famous cover from the Viking Press edition we all read in high school.

This production certainly reminds us how personal hell can be.