Richard Leigh, a physicist and engineer, once labored to improve the efficiency of boilers and air conditioners. But facing the enormous stresses that human energy use imposes on the planet, he tired of "making something better by 10 percent." Scientists have warned that to avert climate disaster, humans must reduce our greenhouse-gas emissions by 80 percent in less than 40 years. Piecemeal improvements, Leigh says, are "not the same thing as looking all the way to the end and saying, ‘This is where we have to go.'"

Today, Leigh is research director at the Urban Green Council, New York City's version of Pittsburgh's Green Building Alliance. In February, the UGC released "90 by 50," a proposal to reduce that city's carbon emissions 90 percent below current levels by 2050.

That is a startlingly ambitious goal: The Pittsburgh Climate Initiative, by comparison, calls for a 20 percent citywide reduction by 2023. Yet "90 by 50" is achievable with current technology ... and in cities with a will to pursue it.

"90 by 50" focuses on buildings, which account for 75 percent of New York City's energy use. But its strategy is also valid in less dense and mass-transit-heavy cities like Pittsburgh — where buildings account for 65 percent of energy use, according to the Pittsburgh Climate Initiative.

Reducing energy use in buildings is infamously difficult: Old buildings — in Pittsburgh, that's most of them — are typically saddled with aging, inefficient HVAC systems. Half of a building's energy goes to heating or cooling spaces, but much of the heat or air conditioning vanishes through gaps and cracks in walls and ducts. Poor insulation and old windows don't help.

That partly explains why, when 50 local businesses and other organizations accepted Sustainable Pittsburgh's Green Workplace Challenge, they'd reduced their collective energy use by less than 4 percent in their first year. Among participants, says the Sustainable Pittsburgh's Matt Mehalik, the most common actions included upgrading light bulbs or fixtures. But lighting is only 9 percent of an average building's energy budget. (GWC participants did average a 28 percent reduction in water use.)

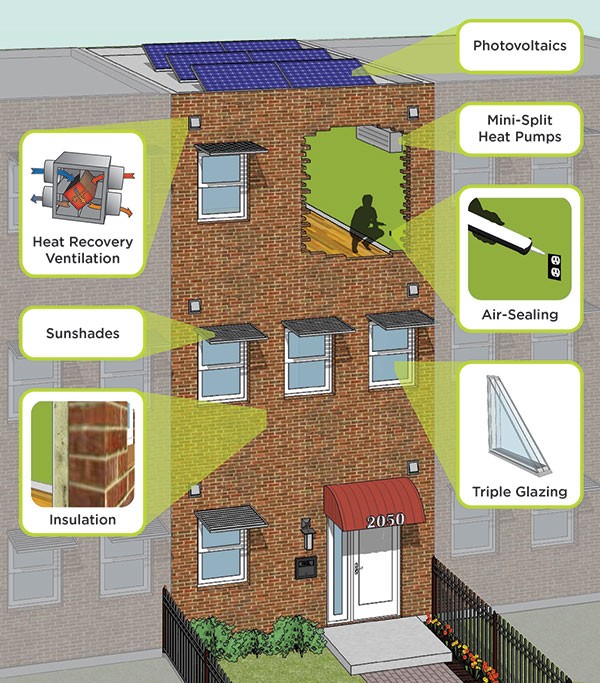

The "90 by 50" approach far exceeds current "green building" standards. The idea is to seal every building in New York — from rowhouses to skyscrapers — tight with caulk and triple-paned windows, halting leakage and halving energy use; then shift heating and cooling duties to efficient electrical heat pumps (including the use of geothermal sources). Energy-recovery ventilators, or ERVs, would warm or cool fresh, incoming air with energy harvested from stale, outgoing air.

All electricity would come from carbon-free sources including wind, solar and nuclear. Energy from coal and natural gas would cease — all without anyone lowering a thermostat. (The report even assumes that on a warming planet, summertime air-conditioning will be universal.)

Because it's predicated on using less energy, and drawing it from more diverse sources, "90 by 50" would also brace New York for a future of volatile energy prices. In Pittsburgh, where soot from coal-fired power plants coats our lungs, such a plan would go a long way toward cleaning the air, too.

[[break here]

None of this is science fiction. Pittsburgh already has several buildings fit for a "90 by 50" world: Phipps Conservatory's Center for Sustainable Landscapes and Sota Construction's "net-zero" houses on the South Side, for instance, are designed to make at least as much energy as they use (mostly from solar panels and geothermal energy). And ACTION-Housing's new "passive house," in Heidelberg, is so air-tight that it has no furnace: It's heated by the people and electrical machines inside, plus an ERV. At 1,600 square feet, the three-bedroom home cost $225,000 to build. But with energy usage 85 percent below average, it's highly affordable to inhabit. Worldwide, there are some 40,000 passive houses, including multistory residential buildings, according to the International Passive House Association.

"90 by 50"-style retrofits exist, too. Recently, Boston's Castle Square, a 500-unit apartment complex, was extensively renovated for a projected energy savings of 72 percent.

What about cost? The UGC estimates the "90 by 50" price tag at $167 billion. But spread over 37 years, the report's authors argue, that's less than half of 1 percent of New York City's gross municipal product. And UGC — which suggests no funding mechanism — says the retrofits would practically pay for themselves in energy savings.

Still, under "90 by 50," retrofitting a single-family house would cost an estimated $26,000. And in Pittsburgh, existing programs to help folks energy-retrofit are small-scale, and often limited to low-income homeowners. Aside from massive public-works projects, how to scale up such a plan?

You could ramp up "energy mortgages," which let property-owners use projected utility savings to finance energy-efficient upgrades. The Federal Housing Administration and some banks already offer energy mortgages, but they're not widely used.

Or how about creating Property Assessed Clean Energy funding in Pennsylvania? In states including California, PACE programs let municipalities issue bonds to make low-interest loans to property owners: The money is used for efficiency renovations and renewable-energy improvements, like solar panels. Property-owners have no upfront costs, and repay the loan through a special property-tax assessment. In California's Sonoma County, a PACE program funded more than 1,500 residential retrofits in three years.

Many PACE programs are now dormant because of legal disputes with Fannie Mae and other financers. But it's the kind of creative idea that might finance a massive retrofit. Meanwhile, on the renewable-energy side, New Jersey's solar-incentive program has made it one of the nation's leading solar states. The program offers loans to help property owners install solar arrays: Property owners keep the energy but sell solar "credits" to energy companies, who count them toward a state-mandated target of using 22.5 percent renewable energy by 2012.

Meanwhile, in Pittsburgh, "We don't have a regional energy strategy at all," says Aurora Sharrard, of Pittsburgh's Green Building Alliance. And while Cincinnati, Ohio, recently began offering residents affordable, 100 percent renewable electricity, Pittsburgh can't — because Pennsylvania law doesn't let municipalities negotiate group rates with utilities.

Pittsburgh does have building-code provisions to promote greener structures — like one allowing buildings to be larger if they're certified green — but they're seldom exploited. These could be made mandatory, or incentives bumped up.

Yet perhaps more than financing instruments, or even laws, Pittsburgh lacks the political will to commit to the needed carbon cuts. A plan like "90 by 50," says Sharrard, "makes you think about the process of how you might get there."

If you set an ambitious goal, she adds, "Even if you fail, you achieve so much in working towards it."