Once a year, Mike Hellman turns in a sheet of paper to the Shepherd Wellness Center to verify he's in care for treatment of HIV.

The sheet is simple: It asks for his physician's name and the date of recent blood tests, and for a signature authorizing the release of information. Once it's turned in, Hellman is eligible to use the Bloomfield center's HIV support services, like group therapy and congregant meals.

But under new federal guidelines for services supporting those with HIV and AIDS, Hellman will have to fill out a five-page form and attach information like a print-out of his lab tests, a paystub … even information on his stock holdings and other assets. And he'll have to do so more frequently. That means providers, like Shepherd Wellness or Allegheny General's Positive Health Clinic, will have to sift through more paperwork to provide care.

"It's just one more hoop to go through," says Mary Gallagher, manager of the Positive Health Clinic. "No one wants to do it, but time is ticking away to get it done."

The changes are part of a mandate from the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, which oversees HIV/AIDS funding across the country, as part of their National Monitoring Standards of such funds released in April. While the changes have been implemented in other states, next year marks the first time they will affect Pennsylvanians.

Clients in care for HIV or AIDS have until Jan. 20 to get "certified" as eligible for certain HIV/AIDS services. And as the deadline approaches, providers and advocates are trying to parse complicated regulations while figuring out how to meet patient needs.

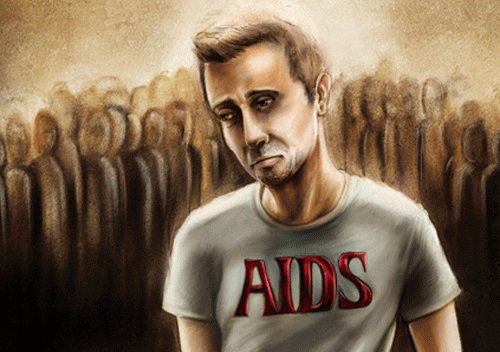

Clients like Hellman, meanwhile, worry that HIV-positive individuals may opt out entirely, cutting them off from critical support.

"I worry about going back to the '80s, when the people who are marginalized already are going to feel even more isolated," says Hellman, of Morningside. "They're not going to be able to participate in the process."

The state receives federal funding through the Ryan White CARE Act, which is meant to pay for services for those who can't afford them. The money is considered a "payer of last resort," meaning agencies typically bill a patient's insurance, Medicare or Medicaid, or tap a private donation to cover the cost.

Ryan White funds cover a swath of services; the recertification is for clients who have been receiving services under a segment known as Part B, which pays for drug therapies; case managers and social workers; housing assistance; and other costs. Locally, funds are overseen by the Jewish Healthcare Foundation, which declined comment.

"Having health insurance … doesn't necessarily guarantee you access to care," says Kevin Burns, executive director of ActionAIDS in Philadelphia. "One of the things Ryan White [funds] do well is remove the bio-psycho-social barriers people have to primary care."

While there have always been reporting requirements for providers, they were largely left to the discretion of regional HIV planning agencies -- until now.

For one thing, federal guidelines have changed the income qualifications for such services. Current patients can make up to 500 percent of the federal poverty level, or $54,450 per year for an individual, to stay in care. New patients can only make up to 337 percent of the poverty level.

"These changes help ensure the payer-of-last-resort requirement is met and enable programs to target Ryan White program resources to those most needy and vulnerable populations," says Elizabeth Senerchia, spokeswoman for the federal Health Resources and Services Administration.

Advocates worry the change will eliminate eligibility for some new patients.

Under the new income thresholds, an estimated 5 to 10 percent of the state's HIV-positive population currently using Ryan White Part B services will no longer be able to get free care, says Weldon King, public-health program manager with the HIV/AIDS division at the state Department of Health.

Still, many agencies don't plan to turn patients away as a result of the new requirements. At Persad and ActionAIDS, for example, officials say they will turn to fundraising to cover the cost of services.

The new process of applying for aid is also more burdensome: The five-page form that beneficiaries like Mike Hellman must fill out comes with extra verification requirements. These range from providing computer-generated lab tests to offering proof of household income with Medicaid letters or tax forms.

"Our already under-resourced staff will spend significantly more time helping patients gather information and tracking down information from medical providers, and that will reduce their availability to actually provide the care," says Betty Hill, of the Persad Center.

Gallagher, of the Positive Health Clinic, says that while some information was required previously, services weren't denied for lack of documentation. "You could provide service if you did not have that information," she says. But now, "you must certify before providing service."

Clients like Hellman say the new requirements raise privacy issues as well. "My concern is where [the new documentation] will be housed and who's going to have access to it," he says. "People are very protective of their status."

Nor is every beneficiary equally capable of jumping through the hoops. Hill, for example, notes that many of Persad's HIV-positive patients suffer from mental-health issues, substance abuse, homelessness or other complicated conditions. The clients "who need help the most are the least capable of organizing themselves to provide the documentation that is needed."

If HIV-infected people drop out of the certification process, it could reduce funding to the entire region: AIDS funding throughout the state is allotted on the number of HIV/AIDS cases that exist within each region.

While federal officials say the certification rate currently doesn't tie into funding, there is concern locally about the ramifications of non-compliance.

"There will be so much fallout if we do not comply," says Doyin Desalu, executive director of the AIDS Planning Coalition of Southwestern Pennsylvania. The coalition looks at data, including service utilization, when planning and setting priorities for the region. "The number of people in care ties into allocations from the federal government."

Part of the impetus for the change, says King at the state health department, is a reinterpretation of the CARE Act by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration. Federal officials did not respond by deadline, but King says federal officials had previously interpreted the law to mean no one seeking service should be turned away -- regardless of income. "That was clarified," King says, to ensure that "someone who has significant resources shouldn't be accessing these services."

Those who've come to depend on those services, meanwhile, will have "to understand that the services … aren't as loose as they used to be," King says. "It's the provider's responsibility to help the clients understand that in order to continue to access services. The dollars being put out there come with conditions we don't have control over."

National advocates, meanwhile, believe the changes are just the latest hurdle to AIDS support. In a political climate where "austerity" is the watchword, funding for the disease has stultified.

"This is what happens when you have a program that for pretty much a decade hasn't seen any meaningful increases to funding," says Matthew Lesieur, vice president for public policy at the National Association of People With AIDS. "The big picture is that there are mouths to feed and not as much food on the table. When that happens, you start prioritizing resources, and it gets to the point where the process denies people access to care."

And local advocates like Bart Rauluk at the Pittsburgh AIDS Task Force worry that not enough emphasis has been placed on assisting the consumer, who ultimately needs the care. "Nobody had the consumer in mind when this was put together," he says. "The real travesty is that no one has prepared our client community for this."