The Art Institute of Pittsburgh wasn't the first choice for aspiring graphic designer Renee Sajewski. But the Michigan native first heard about the school from an art teacher, and a friend who had good experiences there. And besides, unlike many other art schools she was looking at, AIP didn't require a portfolio.

When she first arrived in the fall of 2001, however, the school was everything she could have hoped for.

"The classes at the Art Institute were very good," says Sajewski. "We were taught very well in the technical part of design. The teachers were awesome; they really cared and the classes were small so in most cases you really knew your teacher." Her instructors gave her a thorough grounding in programs like Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop and InDesign. All in all, Sajewski says, "I definitely feel I walked away with a good education and skill sets for my field."

But when she graduated in 2005, she also walked away with a sizable debt.

Her bachelor's degree in graphic design cost her more than $78,000, and that didn't even cover her living expenses. Sajewski borrowed the money for school, which she did by taking out loans from federally backed college-loan programs and private lenders. There's nothing strange about students taking on debt to pay for college, but the amount Sajewski borrowed was unusual.

By the time she graduated, Sajewski had amassed $140,000 in debt.

Today, she is making monthly loan payments of $600; next year that amount will increase to $750, and $950 the year after that. It took Sajewski nearly a year to find a job in her field, and while she is getting by for now, she says, "It feels awful to have paid for an education and basically get paid minimum wage after taxes and my loans are paid."

But for the Art Institute's parent company, Pittsburgh-based Education Management Corp., Sajewski's tuition -- and that of 97,000 students enrolled in schools nationwide -- has already paid off. Just this February, the company announced that in its most recent fiscal quarter, the company had earned $445 million in revenue.

"We are pleased with our strong financial performance," the company's CEO, Todd S. Nelson, announced. And with good reason: Nelson himself makes $1.2 million per year in salary and bonuses. Unlike more established colleges and universities, Nelson's company teaches students for profit, and business has been good.

From its Downtown headquarters, EDMC presides over 83 schools in 26 states and two Canadian provinces. Most of those schools, like the Art Institute of Pittsburgh, focus on careers such as graphic design, culinary arts or video production. And at most of them, students will pay more for a two-year or four-year degree than their counterparts at more traditional colleges and universities.

EDMC bills itself as being "among the largest providers of private post-secondary education in North America," but that's not the only reason it has attracted attention. Before coming to Pittsburgh, Nelson was at the center of a controversy surrounding another for-profit school -- a controversy in which investors and federal education officials alike found fault with the school's aggressive marketing strategies.

And some critics contend that for-profit schools like EDMC are built on the backs of indebted students ... students who have much more to lose than their alma mater does.

"It is extremely hard to pay [the loans] with my income," Sajewski says. "I have accepted the fact that I will be in debt probably the rest of my life."

Walking down AIP's second-floor display of alumni professional works, Alumni Director Dave DiBella proudly shows off the work of some of the school's graduates. Many of them are familiar: Frownie, the mascot of the King's restaurant chain; screenshots from the popular video game Halo 3; a commemorative Elvis stamp from years ago.

"You probably don't go through your day without seeing something that was created by a graduate of this school," DiBella says.

And the Art Institute's president, George Pry, says at AIP you're paying for not just the coursework, but also for career counseling and an alumni program that connects you to a nationwide network. "You're paying for the reputation, [and] AIP's name is one of the top-notch names out there," says Pry. "You're also paying for a bite of the national picture. We have over 40 art institutes out there. Do you want to know about the job market in Los Angeles? We've got a couple institutes out there, and we know what the job market is."

AIP students are recruited by companies like American Eagle and American Greetings card company, boasts DiBella, whose job is to keep in touch with the school's alumni, connecting them with potential job opportunities.

"A grad always has the option to come back to me and see if I can give assistance in their job search, regardless of how long it has been since they graduated," DiBella says.

Katie Speers, of AIP's career services office, says roughly half of the school's graduating students find jobs after graduation, thanks to leads from the school. She says her office tries early on in a student's education to get them involved in planning for their careers. They also help them develop a portfolio that will attract future employers.

"We work with them while they're students to help them develop freelance opportunities and internships," she says. "We really want them to know what it's going to take to get a job when they graduate. They need to know that experience means success."

And success is what many Art Institute students have found.

While attending Westminster College, Zach Barrish decided to pursue an interest in graphic design by transferring to AIP in his junior year. "I already had two years at Westminster when I arrived here and they started me right in on accelerated courses," Barrish says. "I learned twice as much in my time here and my experience was really great.

"I knew when I left that I was capable of being a good designer because of the education I got here at AIP."

Students like Barrish "are willing to pay money because they know there's a far greater chance that when they graduate they'll be able to find a job," says Harris Miller, president and CEO of the Career Colleges Association, which represents for-profit educators and institutions.

In financial filings, EDMC has claimed that slightly less than 9 out of 10 of the students that graduate from its programs find work in their field of study within six months of graduating. But the company also gives itself some wiggle room; the 9-out-of-10 statistic does not include some 13 percent of graduates who are not working in their field for reasons including death, active military service ... or those who are "continuing in a career unrelated to their program of study because they currently earn salaries which exceed those paid to entry-level employees."

For example, Pry says, imagine a manager at Wal-Mart who studies design, but stays at Wal-Mart after graduating because the $25,000 or so he would make as a designer doesn't come close to what he was already earning.

The numbers also don't include a much larger group of students: those who drop out before completing their studies. Just 52 percent of students who enroll in the Art Institute end up completing their program within six years. Pry says that "persistence rate" is comparable with other for-profit schools. But the average for traditional public four-year colleges and universities, according to a 2003 study from the American Federation of Teachers is 76.8 percent.

Such drop-out rates are one reason "our members have a major concern with publicly traded for-profit colleges," says David Hawkins, director of public policy and research for the National Association for College Admission Counseling. "These companies have developed a business model that at the end of the day has no regard for the student.

"A lot of these schools offer these degrees at a very high price and they don't usually take the time to see if the student is even compatible with that course of study," says Hawkins. "They convince students to come to their schools with the promise of job placement after graduation, but in a lot of instances they can't find a job or they find one that doesn't pay them much more than then if they didn't spend $80,000 to go there."

The NACAC is made up of some 10,000 counselors in high schools and traditional, nonprofit colleges. Some of Hawkins members, then, work for colleges that are competing with for-profit schools.

"If this were just a business, then these schools would be out of business," Miller counters. "If they didn't provide quality education or weren't able to place students in jobs after graduation, they would absolutely be out of business.

"Neither a community college, or the University of Pittsburgh for that matter, can say they find jobs for their students. I love Pitt, I graduated from there, but nobody knows what happens to their students after graduation. Nobody is criticizing the number of history degrees they give out and ask whether those students have found work.

"Traditional universities have gotten more selective both academically and socio-economically," Miller adds. "Rather than providing a path for someone in a lower economic class to move into the upper-middle class, they'd rather help the upper-middle class stay there. Many of our clients don't come from a place like Mount Lebanon with two parents with a big house to co-sign for their education. Our students are 26- and 27 year-old single parents with poor or no credit to speak of, and they still deserve a chance at an education."

But to get it, many of those students are paying upper-middle-class prices.

"For-profit schools are more likely to service lower-income students -- anyone who can come up with the tuition payments," says Mark Kantrowitz, who publishes a college-financing Web site www.finaid.org, and studies trends in higher education.

And those tuition payments are often much higher than they might be somewhere else.

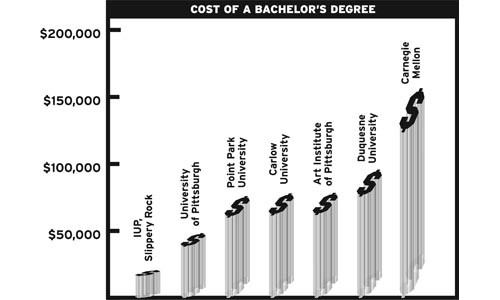

A bachelor's degree from the Art Institute of Pittsburgh costs $78,480. A two-year associate's degree in graphic design would cost $45,300, according to the Art Institute's own Web site.

By comparison, a bachelor's degree from the University of Pittsburgh's College of Arts and Sciences costs roughly $48,400. A four-year degree at Indiana University of Pennsylvania costs just under $21,000.

Schools like Pitt and IUP receive state funding, which helps them keep costs down. As a result, the Art Institute is more comparable to nearby private schools like Point Park University ($76,000 for four years) and Carlow University ($78,000).

So how do students who lack upper-middle-class assets pay for an expensive school? By taking out student loans. As Miller puts it, "Students with modest means need to borrow money to get an education."

Student debt is the fuel that EDMC and other for-profit schools run on. According to EDMC financial filings from 2007, roughly 70 cents out of every dollar the company earns in net revenue comes from federally backed financial-aid programs. Most of that aid is in the form of loans which must be paid back after graduation. And credit counselors say that such loans can be especially pernicious; even declaring bankruptcy will not remove the obligation to pay them back.

"Unfortunately, people don't save up to pay for higher education and they have to take out $50,000, $60,000, $70,000 in loans," says Pry. "While I wish it could be significantly less than that, I feel very assured that it's well worth the price."

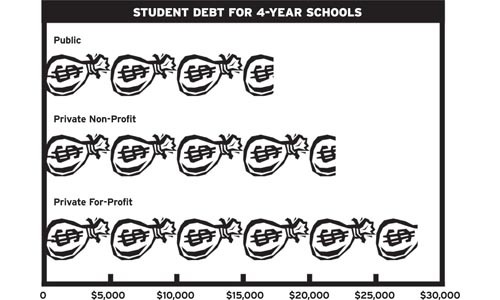

According to Kantrowitz, nearly 9 out of 10 students at for-profit schools borrow money to pay for their education; at a nonprofit public university, just over 6 out of 10 students do. The discrepancy is even higher for students interested in a two-year associate's degree: Nine out of 10 students at a for-profit school will go into debt to pay for it, while only 1 out 3 students will do so at a nonprofit school.

And not surprisingly, the debt incurred at schools like AIP is much larger: Kantrowitz says that students graduating from a four-year, for-profit school have a cumulative debt of $28,138, compared to the $17,277 an average graduate at a nonprofit college will incur.

"With these numbers, it should come as no surprise that students at the for-profit institution are more likely to default," Kantrowitz says.

Kantrowitz says there are ways to avoid severe student-loan debt once you graduate, like never borrowing more than your expected starting salary out of college. "If you borrow more than twice that, there's a good chance you're going into default."

By that standard, the student Pry imagines borrowing $70,000 might be in trouble. The Art Institute's own figures show that the average graduate with a bachelor's degree in graphic design earns roughly $29,500 after graduation.

"The problem is most students don't even consider the money aspect of their education when they enroll," Kantrowitz says. "When you're in school, going to classes, you're not worrying about the debt piling on. You don't realize how bad it is until you graduate."

It's not for lack of trying on the school's part, says AIP President Pry: "When a student enrolls, before they sign up and are committed to all the money, we are giving them what their total cost is. We show them what we know they expect to get in financial aid, what their expected payment plan is in order to make that all the way through." Students sign lengthy enrollment agreements, which detail the costs they should expect to incur, and also a personalized budget breaking down the money they have borrowed and an agreed-upon payment plan.

But when a school is offering you a chance to pursue your dream job, who pays attention to balance sheets?

"I honestly didn't know what I was getting into when it came to the amount of debt I was signing on for," says Jon Dodge, who graduated from the Art Institute in 2006. "Yes, they sat me down and had me sign forms, but when you're 18, 19, 20 years old, you're excited about going to school, learning to draw. You're not paying attention to any of the stuff that affects you once you're out of school.

Dodge didn't want to discuss the size of his loan debt. Now on his third job since graduating, he says the debt is manageable even though it remains "an annoyance every time I cut that student-loan check." Still, "I'm not in as bad a shape as some people I went to school with," he says from his home in Cleveland, where he now runs his own commercial entertainment Web site (www.curiousread.com). "I know a lot of people who took out personal loans" to cover living costs in addition to tuition, "and they're not doing so well." And the forms that students review at the Art Institute don't cover private loans students take out to cover living expenses.

Even so, Miller says it's insulting to think students at for-profit schools don't know what they are getting into.

"I think it's a little disingenuous to say that student was pushed too hard into going to a particular school or they don't understand their debt obligations once they graduate. That assumes that people of a lower income are more susceptible to those types of tactics. It makes the student sound stupid because they're choosing to pay $40,000 for the same thing that they could get elsewhere for $15,000. But it's not the same thing and they're not stupid. ... They're not here because they saw an ad on TV or talked to someone on the phone. They're here because they did the calculations and they made an informed choice."

"I don't think a lot of these students know what they are getting into until they're out of school and thousands of dollars in debt," argues David Hawkins, of the national college counseling association. "I think in these institutions there's an unhealthy focus on the numbers and not enough of a focus on the students, and that's worrisome.

"The bottom line for these companies is their first concern, not the students," says Hawkins. "They're more concerned about Wall Street downgrading their stock."

By that standard, EDMC has some things to worry about.

The company was a publicly traded corporation until June 2006, when it went private. But just a year and a half later, it reversed that decision: In December 2007, the company announced plans to issue $500 million in company stock. The timing of the decision was notable: It came toward the end of Todd S. Nelson's first year as CEO -- and toward the end of a trial in which he was accused of concealing information from those investing in his previous employer.

When Nelson arrived at EDMC in February 2007, he had an extensive resume. The 48-year-old had nearly 20 years of experience with the Apollo Group Inc. -- the parent company of the University of Phoenix, the nation's largest for-profit educator. In 1998 he was named Apollo's president, and added the title of CEO in 2001. According to Forbes magazine, Nelson earned more than $32 million in 2004 alone, making him the 10th highest-paid top executive in the country.

But for Nelson, things were beginning to go sour.

In September 2004, the Arizona Republic newspaper obtained a federal Department of Education report that criticized the University of Phoenix's aggressive recruitment tactics, which included paying recruiters based on the number of students they enroll, a violation of federal law.

Federal investigators discovered "several examples of compensation and sales practices the department says range from illegal to unethical to aggressive," the Republic reported. "[E]nrollment counselors interviewed by regulators told of a glassed-in isolation room, called the 'red room,' where under-performers were put on display to work the phones under intense management supervision. A group of San Jose recruiters recalled being told heads would be on a chopping block if its numbers didn't come up; another recruiter said her manager told her she couldn't afford time away from the phone to go to New York for her grandmother's funeral."

Nelson told the Republic the report was "very, very unfair" and inaccurate.

Apollo officials were issued the report in February 2004; however, they kept it under wraps until the Republic uncovered it in September of that year. Although they admitted no wrongdoing, Apollo agreed to pay a record $9.8 million to settle the government's claims. Nelson himself resigned the firm in January 2006.

But while his job had ended, Nelson's problems had only begun. In October 2004, Apollo shareholders had filed a class-action lawsuit against Nelson and the company itself. Withholding the report, the plaintiffs charged, damaged the company's stock price.

The trial began in November 2006, and according to published reports, Nelson testified that he had kept the report under wraps because he worried the company's stock would fall.

The lawsuit also revealed the fact that Nelson had resigned under duress. John Sperling, the company's chairman of the board, said in a deposition that Nelson was forced out because "I did not believe he was performing his CEO functions in a proper manner.

"I think he was mainly concerned with anything that would cause the stock to drop. ... [H]e was preoccupied primarily with the stock price and not with the functioning of the company."

After a protracted trial, the jury ruled against Nelson and Apollo in January of this year. The verdict ordered the defendants to pay roughly $280 million to its shareholders. In parceling out blame, and thus liability, the jury ruled the company was 60 percent responsible for damages, Nelson was 30 percent responsible, and Apollo's chief financial officer was 10 percent liable. Unless Nelson's contract specifically indemnifies him against lawsuits, the ruling could cost him $84 million.

Apollo is appealing the jury's verdict, and officials at the Art Institute say that while EDMC is the parent company, the schools maintain their independence, acting as their own entities with its own leadership and board.

Some staffers were concerned about Nelson's past history at Apollo, AIP President Pry acknowledges. "We all heard about the issues at the University of Phoenix, but we haven't seen anything like that here," he says. But Nelson "has been all about establishing quality about where we want to go in the future.

"Knowing Todd the way I now know him, I am sure that there's a good and healthy other side of that story. But that was then and he's here now with us and there are many checks and balances. ... I don't believe anything like that would happen here, if something negative actually happened."

City Paper attempted to contact Nelson regarding the situation with the Apollo Group and several other questions regarding EDMC. CP was asked to provide written questions, which it did. But once the questions were provided, EDMC declined to answer them. An EDMC spokesperson replied that the company was in a "quiet period," mandated by federal law when a company is preparing to issue stock. "During this period, federal securities laws limit what information we can release to the public," said Jacki Muller, a spokesperson for EDMC. "During the quiet period, we are not responding to press inquiries related to Education Management." Since the company has not set a date for issuing its stock, there's no telling when that quiet period will elapse.

But in financial filings, EDMC has acknowledged that it has faced a handful of inquiries from attorneys general in other states.

In a Feb. 14 Securities and Exchange Commission filing, EDMC acknowledges that attorneys general in at least three states -- Massachusetts, Oregon and Illinois -- have sent "investigative demand" letters to EDMC. In Massachusetts, the company says investigators were seeking information about "alleged unfair and deceptive student lending and marketing practices" carried out at the EDMC-owned New England Institute of Art. The filing says that while the state has dropped the investigation into that matter, it is still looking into the school's "relationship with student-loan providers."

Similar questions are apparently being asked at the Art Institute of Portland and four locations in Illinois. According to the financial filing, state officials have sought information about "the relationships between the schools and providers of loans to students attending the schools."

Natalie Bauer, a spokesperson in the Illinois Attorney General's office said in an e-mail: "I can confirm that the Illinois Attorney General's office sent a subpoena to Education Management Corp. as part of an investigation into school lenders."

Bauer would provide little information about the nature of the "relationships" being investigated. However, Bauer adds the investigation was based on current investigations going on in New York. In that state, which in 2006 placed a moratorium on career colleges offering new programs because of quality-control concerns, Attorney General Andrew Cuomo has been investigating the relationships between certain lenders, such as Sallie Mae, and schools.

Cuomo is investigating deals between the lenders and the schools that made the financial institution "preferred lenders" in exchange for kickbacks to the schools. According to an article from the July 2007 Career College Central magazine, the kickbacks meant money for things like scholarship funds at nonprofits. But, "for the smallest of for-profit schools it increased the bottom line -- a revenue stream that could be as important as the tuition itself. The problem was that students didn't know about the deals even though they were ultimately paying the price in the form of interest on their loans."

For-profit schools face another hurdle as well. Since companies like EDMC derive most of their income from students borrowing to pay for their education, the recent credit squeeze is likely to hurt them. Student-loan companies such as Sallie Mae, and nonprofits like the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency have complained of shrinking financial resources. That will make it harder for schools like the Art Institute to enroll new students

According to a Feb. 19 story in The New York Times, "loan companies are tightening standards for private loans to students who have poor credit or to institutions with poor graduation rates. Private loans are not guaranteed by the federal government and can carry rates as high as credit cards."

Pry says a lot of colleges are in the same boat because of the economic climate and because "alternative loans [are] going away and states ... are starting to pull back from grants and the other types of financial aid that's out there."

Which means that EDMC, which relies on that financial aid much like its students do, could be facing the same kind of financial uncertainty that plagues even students who are pleased with the education they get. Students like Jon Dodge.

"I know that I am a better designer and I know that I learned more and got a better education at AIP than my colleagues who went to lesser and less expensive schools," Dodge says. "But the thing is, we're sitting there at the same job getting the same wage.

"If I had to do it all over again and my choice was to not become a graphic designer or go to AIP, I would go to AIP again. However, if my choice all over again was to go to AIP or a less expensive school like the guy sitting next to me, I'd go somewhere else. As good as my education was, I don't think it was worth all the money that I paid."