Sometime shortly before 1907, Carnegie Tech Board member Lucian Scaife sat at the all-male Duquesne Club and wrote thoughtfully: "To make and inspire the home; to lessen suffering and increase happiness; to aid mankind in its upward struggles; to ennoble and adorn life's work, however humble; these are woman's high prerogatives." Surely these sentiments should have evaporated into the mists of pre-suffrage history. Instead, unfortunately, they form an inscription featured prominently in the entry rotunda of CMU's Margaret Morrison Hall.

Much more recently, Rebecca Deutsch, a 2004 CMU graduate who now develops operating systems as a program manager with Microsoft, re-examined the inscription. "It didn't relate to my experience," she explains. "I'm a woman in computer science. The gender issues around that have always interested me," At the same time, Deutsch's work as a student interested the university. Because of her outstanding academic performance, CMU selected her to be a Fifth Year Scholar, one who studies for an extra year at the University's expense with the freedom to explore pursuits outside her major.

Deutsch has done academic and extra-curricular work in art and women's studies, so among her other courses, she enrolled in a public art class with artist and professor Bob Bingham. She wanted to find ways to reflect women's experiences at CMU more accurately than a string of chauvinist epithets written in an all-male club a century ago. The building's historic status prevented Deutsch from proposing alterations to the outside, so she examined the oddly shaped interior vestiges where the exterior rotunda meets the interior stairwell. "It's really a curious unused space with a lot of weird shapes and angles," she describes. Still, it seemed ideal for her purpose, and she liked the metaphorical sense of transition: "Women were on the outside at first, but they came to be on the inside."

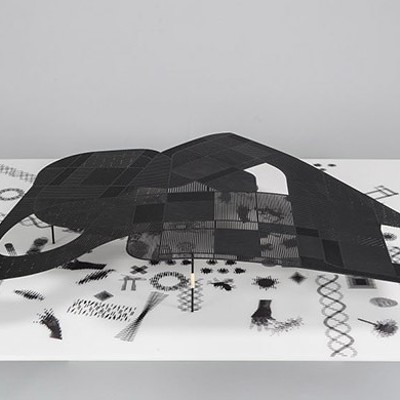

Deutsch thought about using collaged images, but chose instead to use text only, eventually applied as custom decals. She scoured histories and course catalogues, then moved to interviews and surveys for more vivid, first-hand experiences of women at Carnegie Tech through the years. Using Photoshop, she artistically arranged selected quotations to move around corners and over arches while still being readable.

Installation was time-consuming. Deutsch raised $9,000 and persuaded Facilities Management to plaster and repaint the necessary spaces.

The results are dramatic. A quote from 1937 laments, "I completed my course in metallurgy, but they gave me a chemistry degree, because the engineering department would not grant degrees to women." Another, from 2000, effuses, "As soon as I started that programming course, I absolutely loved it. I had a great feeling of having my own creation, an art in itself."

The recollections develop a lively history with the energy unique to first-hand narratives. They reflect the triumphs of education in the industrial city as well as the pitfalls of fading, but continuing gender discrimination. It's a history of the neoclassical architecture that columns and capitals simply can't tell by themselves.

Deutsch's installation also puts the building's original design in richer, more complex perspective. Henry Hornbostel's architecture is historic and beautiful, but the rotunda may be as troubling as the quote inscribed in it. After all, the two-story oval of yellow brick and terracotta arches is ornamental, subservient and almost useless, as if it were a direct analogy to Scaife's unfortunate text. By contrast, it is only inside where the "real work" happens in "functional" spaces -- a much more supposedly masculine sensibility. This separation of ornament and function seems to reflect an outdated sense of separation between female and male.

That's why, until now, those odd spaces off the stairwells have been neglected and underappreciated. They don't fit into the original design's conception of either female or male in architecture. Accordingly, Deutsch's engagement of them in the cause of feminist history adds to the richness of her project. She shows that to understand why outdated conceptions of male vs. female are stifling, a good approach is to examine the phenomena that don't really fit in either category. Like a neglected stairwell, or a woman engineer.

The building remains, and history persists, with the help of Deutsch's work to elucidate it. Women still leave Carnegie Mellon to go do Windows; that just means something entirely different than it did in 1907.