Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body explores the artist’s relationship with bodies — his and others

It’s tempting to conclude that Warhol was heavily driven by dissatisfaction with his own hide

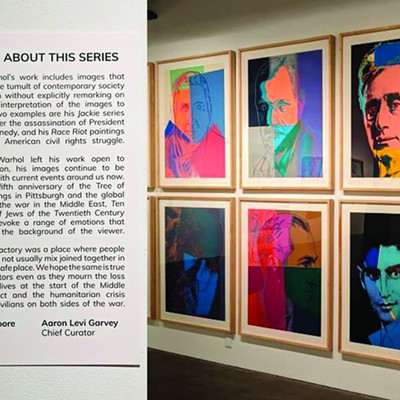

Andy Warhol’s “Physiological Diagram” (1985)

ANDY WARHOL: MY PERFECT BODY

continues through Jan. 22. The Andy Warhol Museum, 117 Sandusky St., North Side. 412-237-8300 or warhol.org

Discerning what motivates an artist is tricky, but you might think it’d be easier with Andy Warhol. Drawn to celebrity and consumer products, Warhol avowedly made a career of manipulating surfaces, and he left behind an archive’s-worth of source materials and other keepsakes for scholars to contemplate. He got a nose job in the 1950s, wore a wig his entire adult life, and strenuously courted the company of people decidedly more glamorous than himself. He was also a young gay man back when that was basically illegal, even in New York City.

So when in Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body, at The Andy Warhol Museum, we see images of mangled, warped or surgically altered bodies, it’s tempting to conclude that Warhol was heavily driven by dissatisfaction with his own hide. Indeed, one of the exhibit’s more provocative assertions is that images of newspaper-ad bodybuilders started appearing in Warhol’s work just as he was transitioning from commercial art to his era-defining pop art — a metaphor that, whether conscious or unconscious, suggests that for Warhol, making art was simply part of the slightly larger project of remaking his unsatisfactory self. “The exhibition,” says its curator, the Warhol’s Jessica Beck, in press materials, “asserts that Warhol’s engagement with Pop started with the body.”

Perfect Body is broadly chronological. Student works like Warhol’s humorously grotesque 1948 self-portrait “Nosepicker II,” hang alongside such expressions of corporeal distress as “Constipated Woman,” “Man With Lines Exuding from Mouth” (read: projectile vomit) and a female nude almost gratuitously covered in lesion-like spots. Nearby loom two alternate versions (1961 and ’62) of “Before and After,” Warhol’s large-scale, pre-soupcan takes on a magazine ad for rhinoplasty, the woman’s nose first hooked, then, suddenly, pert.

Things get rougher with four large silkscreens from the Warhol’s “death and disaster” series, whose source materials were news photos. In 1963’s “Ambulance Disaster,” a body sprawls headfirst from the smashed vehicle’s window; the lower of two frames is nearly identical except that the victim’s bloodied face is obscured by a splash of pigment. By contrast, the Empire State Building suicide jumper in “1947 White” (1963) somehow still looks magazine-cover-ready after plummeting 86 stories, resting face-up in the body-shaped dent she’s made in the parked limo as though it were a bed of silken cushions.

Elsewhere, Perfect Body highlights Warhol’s return, in the ’80s, to his early pop style. A few large-scale late works utilize medical illustrations, like the wall-sized “Physiological Diagram”: the outline of a headless body, its digestive tract rendered in orange, with a broken-out enlargement of the heart floating alongside what looks, cryptically, like a “play” symbol from an electronic device. The circa-1982 “Physiological Drawing Diagram (Penis in the Chest)” is another outline, but unnervingly, the headspace is blank except for two black spots bold as bulletholes, and depending from one pec is the silhouette of male genitalia. Such anatomical disarray recalls the aftermath of Warhol’s 1968 shooting; in an adjacent display case, a 1987 Richard Avedon photo of Warhol showing his many scars joins an alarming Jack Smith photo of a limp Warhol being borne into the ambulance, and such memento mori as one of Andy’s custom wigs and his collection of creepy metal dental molds.

So there’s plenty of evidence to support the labels for the show’s several sections, which trend unhappy: “Trauma,” “Torment,” “Shame.” But even in this exhibit, they’re not the whole story. Warhol’s early fine-art work exhibited here also includes his “Boy Portraits” of the 1950s, publicly exhibited (and surely a bit shocking at the time) ink sketches of three barechested young men and one naked, each bedizened with little cartoon hearts. The naked boy’s single heart adorns his glans.

This section of the exhibit is labeled “Desire,” but even outside of it, the body is often celebrated, uncritically if sometimes amusingly. Video projections include excerpts of both Warhol’s 1963 epic “Sleep,” featuring his lover, John Giorno, and “Superboy” (1966), the latter a cut of prime beefcake. Nudes like “Shaved Vagina” and “Torso From Behind,” painted in peach and deep black shadow, are as cheeky as the five aligned butts in 1977’s “Torso Posterior View (5).” The acrylic-and-silkscreen-ink work “Jean Michel Basquiat” (1984), depicts its famous subject in negative, sectioned off, and with an extra arm, but it’s still clearly a celebration of male beauty.

All this prompts plenty of questions. If “Warhol’s engagement with Pop started with the body,” why did it reach its apotheosis with soup cans and Brillo boxes? As the exhibit’s introductory photo display, titled “Warhol’s Beauty Problems,” notes, Warhol suffered terrible childhood skin problems and as a young man visited beaches fully clothed. He had a conflicted relationship with his body; many of us do. Yet Warhol also clearly loved other bodies. So why was he at one point consumed by depicting them catastrophically killed? And how much of what one might view as self-loathing, anxiety or torment — going back to juvenilia like “Nosepicker II” — could as easily be interpreted as the result of a simple desire to shock that Warhol maintained into adulthood? And how much of his affection for anatomical illustrations and unironical line drawings of bodybuilders and nose jobs merely reflected his camp sensibility?

While there’s no one right answer, Warhol plainly came of age (and came of age plainly) in the era of widespread plastic surgery and rising notions of physical “perfectability.” He worked out with dumbbells — watch him do pushups on Andy Warhol’s TV! — and was, according to wall text here, never satisfied with the results of his own nose job.

Yet later in life, according to exhibit text, he did become more comfortable with his body. And My Perfect Body is capped with a seeming note of acceptance, even beatitude. “The Last Supper (Be a Somebody with a Body)” (1985-86), a large-scale acrylic painting made to be viewed under black light, was part of a series commissioned to hang in a Milan commercial building across the street from the original. It depicts a cartoon bodybuilder beneath the title motto and alongside three identical images of Leonardo’s Christ, eyes closed and head bowed, rather doleful — perhaps like someone realizing he was stuck working with what he’d been born with.

So when in Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body, at The Andy Warhol Museum, we see images of mangled, warped or surgically altered bodies, it’s tempting to conclude that Warhol was heavily driven by dissatisfaction with his own hide. Indeed, one of the exhibit’s more provocative assertions is that images of newspaper-ad bodybuilders started appearing in Warhol’s work just as he was transitioning from commercial art to his era-defining pop art — a metaphor that, whether conscious or unconscious, suggests that for Warhol, making art was simply part of the slightly larger project of remaking his unsatisfactory self. “The exhibition,” says its curator, the Warhol’s Jessica Beck, in press materials, “asserts that Warhol’s engagement with Pop started with the body.”

Perfect Body is broadly chronological. Student works like Warhol’s humorously grotesque 1948 self-portrait “Nosepicker II,” hang alongside such expressions of corporeal distress as “Constipated Woman,” “Man With Lines Exuding from Mouth” (read: projectile vomit) and a female nude almost gratuitously covered in lesion-like spots. Nearby loom two alternate versions (1961 and ’62) of “Before and After,” Warhol’s large-scale, pre-soupcan takes on a magazine ad for rhinoplasty, the woman’s nose first hooked, then, suddenly, pert.

Things get rougher with four large silkscreens from the Warhol’s “death and disaster” series, whose source materials were news photos. In 1963’s “Ambulance Disaster,” a body sprawls headfirst from the smashed vehicle’s window; the lower of two frames is nearly identical except that the victim’s bloodied face is obscured by a splash of pigment. By contrast, the Empire State Building suicide jumper in “1947 White” (1963) somehow still looks magazine-cover-ready after plummeting 86 stories, resting face-up in the body-shaped dent she’s made in the parked limo as though it were a bed of silken cushions.

Elsewhere, Perfect Body highlights Warhol’s return, in the ’80s, to his early pop style. A few large-scale late works utilize medical illustrations, like the wall-sized “Physiological Diagram”: the outline of a headless body, its digestive tract rendered in orange, with a broken-out enlargement of the heart floating alongside what looks, cryptically, like a “play” symbol from an electronic device. The circa-1982 “Physiological Drawing Diagram (Penis in the Chest)” is another outline, but unnervingly, the headspace is blank except for two black spots bold as bulletholes, and depending from one pec is the silhouette of male genitalia. Such anatomical disarray recalls the aftermath of Warhol’s 1968 shooting; in an adjacent display case, a 1987 Richard Avedon photo of Warhol showing his many scars joins an alarming Jack Smith photo of a limp Warhol being borne into the ambulance, and such memento mori as one of Andy’s custom wigs and his collection of creepy metal dental molds.

So there’s plenty of evidence to support the labels for the show’s several sections, which trend unhappy: “Trauma,” “Torment,” “Shame.” But even in this exhibit, they’re not the whole story. Warhol’s early fine-art work exhibited here also includes his “Boy Portraits” of the 1950s, publicly exhibited (and surely a bit shocking at the time) ink sketches of three barechested young men and one naked, each bedizened with little cartoon hearts. The naked boy’s single heart adorns his glans.

This section of the exhibit is labeled “Desire,” but even outside of it, the body is often celebrated, uncritically if sometimes amusingly. Video projections include excerpts of both Warhol’s 1963 epic “Sleep,” featuring his lover, John Giorno, and “Superboy” (1966), the latter a cut of prime beefcake. Nudes like “Shaved Vagina” and “Torso From Behind,” painted in peach and deep black shadow, are as cheeky as the five aligned butts in 1977’s “Torso Posterior View (5).” The acrylic-and-silkscreen-ink work “Jean Michel Basquiat” (1984), depicts its famous subject in negative, sectioned off, and with an extra arm, but it’s still clearly a celebration of male beauty.

All this prompts plenty of questions. If “Warhol’s engagement with Pop started with the body,” why did it reach its apotheosis with soup cans and Brillo boxes? As the exhibit’s introductory photo display, titled “Warhol’s Beauty Problems,” notes, Warhol suffered terrible childhood skin problems and as a young man visited beaches fully clothed. He had a conflicted relationship with his body; many of us do. Yet Warhol also clearly loved other bodies. So why was he at one point consumed by depicting them catastrophically killed? And how much of what one might view as self-loathing, anxiety or torment — going back to juvenilia like “Nosepicker II” — could as easily be interpreted as the result of a simple desire to shock that Warhol maintained into adulthood? And how much of his affection for anatomical illustrations and unironical line drawings of bodybuilders and nose jobs merely reflected his camp sensibility?

While there’s no one right answer, Warhol plainly came of age (and came of age plainly) in the era of widespread plastic surgery and rising notions of physical “perfectability.” He worked out with dumbbells — watch him do pushups on Andy Warhol’s TV! — and was, according to wall text here, never satisfied with the results of his own nose job.

Yet later in life, according to exhibit text, he did become more comfortable with his body. And My Perfect Body is capped with a seeming note of acceptance, even beatitude. “The Last Supper (Be a Somebody with a Body)” (1985-86), a large-scale acrylic painting made to be viewed under black light, was part of a series commissioned to hang in a Milan commercial building across the street from the original. It depicts a cartoon bodybuilder beneath the title motto and alongside three identical images of Leonardo’s Christ, eyes closed and head bowed, rather doleful — perhaps like someone realizing he was stuck working with what he’d been born with.