During the 20th century's Great Migration, 6 million African Americans moved from Southern states into Northern, Midwestern and Western cities seeking jobs and fleeing racial violence. While such a move offered economic mobility to some, many people continued to experience racial tension, discrimination and poverty. Much as with today's Latino immigrants, the move offered a chance for something better, but not without sacrifice.

In Common Ground: Affrilachia! Where I'm From, an art exhibit at the August Wilson Center for African American Culture, two ceramic wall sculptures by Kelly and Kyle Phelps offer a perspective on this very subject. "The Meek" shows two Latina factory workers despondent over the closing of their plant. The artists, twin brothers raised in Indiana, translate their family's experience as factory workers into commentary about the struggles of average men and women.

The Phelps brothers' other piece, "Carlita," depicts a weary cleaning woman leaning against her cart with an American flag as a backdrop. The piece refers to the mostly invisible work done by undocumented people in the U.S., and offers a contemporary twist on the iconic 1942 Gordon Parks photograph "American Gothic, Washington, D.C.," in which an African-American cleaning woman stands solemnly in front of the American flag framed by her mop and broom.

Images like these resonate in Pittsburgh and other northern cities of the Rust Belt. But Pittsburgh is actually located right in the middle of Northern Appalachia. While the popular imagination places Appalachia somewhere in the backwoods of Tennessee or Alabama, it is actually a region that stretches across 13 states, from northern Mississippi to southern New York. Common Ground brings together work by African-American artists from this vast region. Taking as its crux the term "Affrilachia," coined by Kentucky poet Frank X. Walker, the exhibition explores the diversity of ideas and styles that emerge from both urban and rural artists who inhabit this geography.

The exhibition is actually a composite made up of two integrated parts. One part is a juried exhibition with works chosen from an open call by Cecile Shellman, the Center's artistic director of visual arts and exhibitions, and Sharif Bey, an assistant professor at Syracuse University. The other part is an exhibition curated by Marie T. Cochran, founding director of The Affrilachia Artist Project.

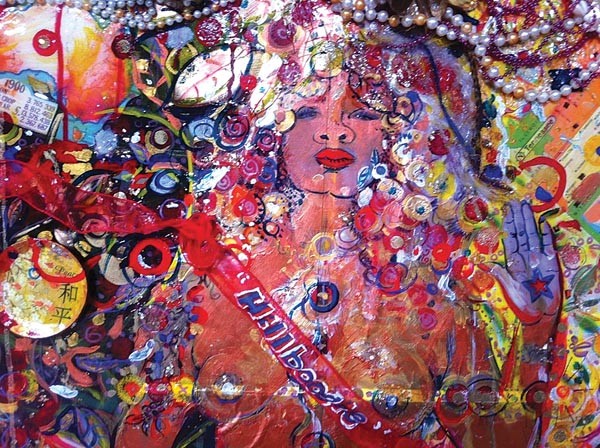

By blending two exhibitions, the organizers cover a lot of ground, but it ultimately does a disservice to the presentation's aesthetic coherence. Small and subtle works, such as Carlos Peterson's "Leviticus 25:33-46," get lost amidst the visual noise. Even the large and boisterous "Hillboogie," by Valeria Watson-Doost, doesn't have the space it needs to be fully appreciated. A smaller, more focused show would better underscore how the particularities of a geographic region, one that is both physical and cultural, have a specific impact on the many facets of identity.

The most noticeable thing about the exhibition is the predominance of assemblage and collage. Many of the artists create altars, figures, quilts and clothing by accumulating and re-purposing materials. Eco artist DeWayne (BLove) Barton uses found objects in "The New Religion." Christine Bethea uses items that have "lived" before in "Adam and Eve." Vanessa German's Nkisi-type figures and LaVerne Kemp's tunic and hat incorporate amulets and charms made from found objects such as keys, shells, beads and buttons. Charlotte Ka's indigo-and-white altar is an amalgam of encaustic, cotton plants, beads, cowrie shells, and a washboard and tub. Willis (Bing) Davis' "Portable Shrine in Homage to the Middle Passage" includes objects given to him by artists who are in this particular exhibition.

Assemblage and collage also animate more two-dimensional pieces, such as quilts by Tina Brewer, Sandra K. German and Mayota Hill that are embellished with items such as shells, beads, lace, coins, antique fabrics and photo transfers. Even Elizabeth Asche Douglas' photograph, "Condemned House," combines multiple views to create a dynamic composition, while Lynn Marshall-Linnemeier's photographs are hand-colored to create textured surfaces. Jo-Anne Bates' abstract prints have a three-dimensionality that comes from incorporating shredded paper.

The syncopated rhythms and textures that are apparent in these pieces echo another theme that runs through the exhibition — African-American music. Other recurrent themes include community and family, religion, history, and images of work and labor. The diversity of themes, styles and mediums are linked by the exhibition design, created by Bally Exhibit, which reflects the mountains and steel mills that make up the landscape of Appalachia. And while its sweep is overly broad, the exhibition is just the first attempt at what is sure to become a much-anticipated annual regional exhibition.