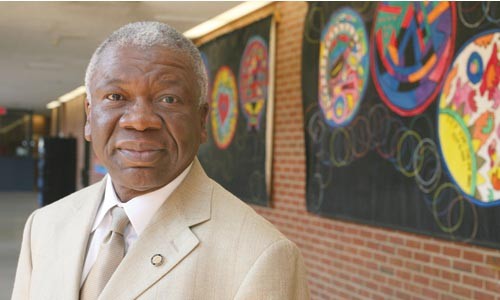

Alex Wilson has worked at the Shuman Juvenile Detention Center since 1980, and has served as executive director since 1991. After 27 years, he has seen every level of juvenile offender pass through the detention center's gates; his last day on the job was May 31.

You've been at Shuman a long time. Was there something in particular that made you think now was the best time to get out?

After 27 years total and 16 as director, I just felt it was time to pass the baton to someone else. You just hit the point when you know it's time.

You started in 1980. Was it easier or harder to relate to these kids as time went on?

It's somewhat different now than, say, the early 1980s and 1990s. Early on, you didn't have gang affiliations. But sadly, it's not gang affiliation nowadays -- although there is some of that. Oftentimes, it's the neighborhood affiliations kids have that get them in trouble. They're constantly at odds with some other kid from another neighborhood. Sometimes, it's kids fighting other kids in the same neighborhood, just a couple streets away. You read about the shootings in the papers every day. It has unfortunately gotten worse.

How do the neighborhood wars of 2007 compare to the problems you saw in the 1980s?

Since drugs have become so prevalent in the past several years, a lot of these situations are rooted in the drug problem. Some of these shootings occur over an argument about drugs -- somebody didn't get all of their money, or what have you -- and that can lead to violence and shootings. Then that violence can lead to someone on the other side retaliating. It's like a Ping-Pong ball back and forth.

How has your advice to these kids changed? Do you talk to them the same way now as you did when you started?

The message has been fairly consistent from the beginning. However, the kids now tend to not want to hear it. Using the example of selling the drugs, talking to that kid about working a regular job unfortunately goes in one ear and out the other. If you think of it in strict economic terms, some of them may be making $400 a week [selling drugs] as opposed to making a whole lot less at Wendy's. So they're unfortunately less apt to listen to you when you try to talk to them about getting a legitimate job.

Has anyone ever come back to you and said that the Shuman Center made a difference?

It's been over 10 years, but there was a young man who played football for one of the local high school teams. He had gotten in some trouble and was here for a while, did his time in placement and got back on the right track. He ended up going to West Virginia University on a football scholarship. He wrote to one of unit workers when he was in his sophomore or junior year at West Virginia and said, "I want to thank you for not giving up on me. I know you thought I wasn't listening, but I do appreciate you trying to help me." That was 10 years ago and it's still so fresh in my mind. You never know how we might touch a kid, so we can never give up.

Has your work at the Shuman Center over the years changed the way you parented your own kids?

Not really. I have four daughters, all of whom are grown, and I pretty much knew the pitfalls going in. I knew it had to start early -- teaching them right from wrong, setting limits and using discipline when there's a need.

What is the message you would leave the people coming in behind you?

We can't give up. It can get trying at times, but we have to keep on doing what we can because some of the kids will be touched. We're certainly aware that we can't save everybody, but if we give up, we lose the battle totally.